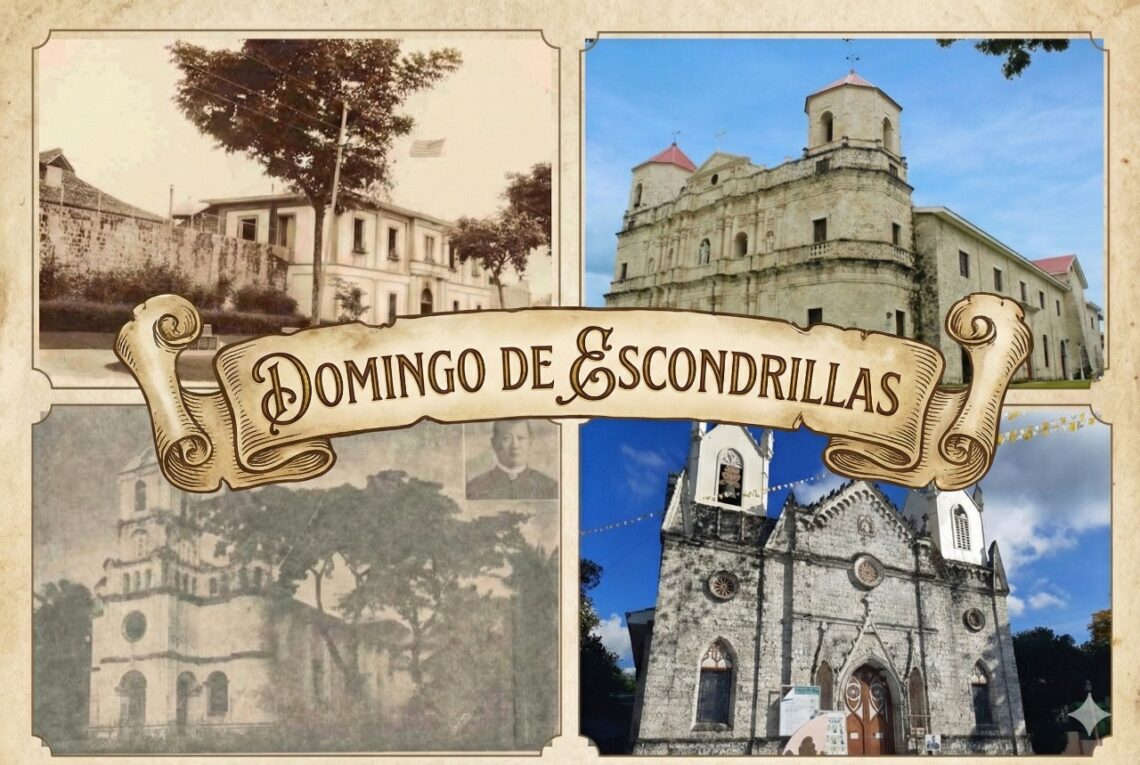

The history of the nineteenth-century Visayas is often told through the ledger books of merchant houses or the revolutionary fervor of the Ilustrados. We speak of the opening of the Port of Cebu in 1860, the sugar boom of Negros, and the sudden influx of British and American capital that transformed our islands from a colonial backwater into a global entrepôt. But rarely do we stop to ask: who built the stage upon which this drama unfolded? When the wealth arrived, it needed to be translated into stone. The silting canals of the Parian and the muddy roads of the hinterlands were insufficient for the new era of commerce. Enter Don Domingo de Escondrillas y Yarza, who entered the port of Cebu in 1855 according to the book: Integracion/Internacion: The Urbanization of Cebu in Archival Records of the Spanish Colonial Period. He settled in what is today, Magallanes street, Cebu City.

Holding the dual titles of Ingeniero and Arquitecto, and serving as the singular Director of Public Works (Obras Públicas) for the district of Cebu, Escondrillas was the technocrat entrusted with the physical metamorphosis of the Central Philippines. He was not merely a builder; he was the filter through which the architectural ambitions of both Church and State had to pass. In a region starved for technical expertise, he became the “lone architect,” a military engineer tasked with civilizing a rugged landscape.His aesthetic was not one of frivolous ornamentation. Born of the military tradition, Escondrillas designed for permanence and defense. His structures possess a fortress-like solidity of being massive, unyielding, and prepared for siege. From the walls of a provincial jail to the naves of Bohol’s grandest church, Escondrillas engineered the modernization of the Visayas, leaving behind a legacy written in coral stone and mortar. Escondrillas’s work is a study in the transition of power. His portfolio spans the secular, the ecclesiastical, and the intellectual, each structure narrating a different chapter of Philippine colonial history.

1. The Cárcel de Cebú – Cebu City (Currently Museo Sugbo)

With plans drawn up by him as early as 1869, the Cárcel del Distrito is perhaps Escondrillas’s most politically charged work. Originally designed as the central penitentiary for the Visayas, it is a masterclass in utilitarian colonial architecture. However, historical analysis suggests a profound transfer of power in its masonry: the construction coincided with the demolition of the Parian Church, the spiritual center of the Chinese mestizo community. Escondrillas repurposed these consecrated coral stones to build the high walls of the state prison, literally dismantling a rival power center to construct an instrument of state control.

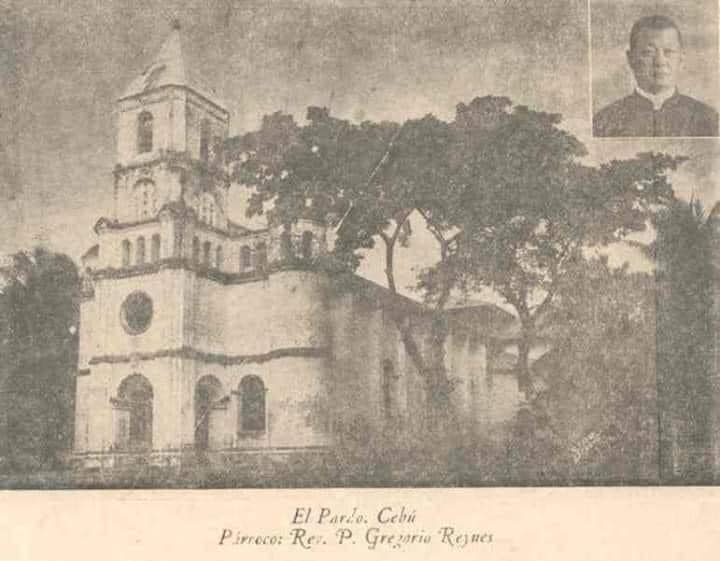

2. The Church of Santo Tomás de Villanueva – Pardo, Cebu

Located in what was then the independent pueblo of El Pardo, this church represents Escondrillas’s departure from the floral Baroque typical of the era. The structure is characterized by a fortress-like composure, utilizing heavy Byzantine-influenced arches and a distinct lack of frivolous ornamentation. It reflects the architect’s military background of a thick, imposing, and designed with a Romanesque rigor that prioritized structural integrity over decorative excess. It stands as a testament to his vision of a disciplined, modernized church infrastructure close to the provincial capital.

4. St. Isidore the Labrador Church – San Fernando, Cebu

Several heritage and local sites list Domingo de Escondrillas as the architect/designer, with the present stone church completed in 1886 and described stylistically as Neo-Gothic. This design differs from his two mudejar-like designs as seen in Pardo and Ginatilan; it exhibits his prowess in designing for different styles.

3. The Church of Nuestra Señora de la Luz – Loon, Bohol

Across the strait, Escondrillas was commissioned to build what was intended to be the “finest church in the Visayas.” Completed in 1864, the Loon Church was a structural marvel that introduced a wide rectangular plan with an internal transept. His engineering audacity was evident in the buttressing; he relied on only two sloping buttresses, trusting the sheer geometry of his thick limestone walls to carry the load. Tragically, the 2013 earthquake reduced this masterpiece to rubble, exposing the mampostería construction that lay beneath the cut stone facade.

4. The Convent of San Nicolas de Tolentino (Malabuyoc, Cebu)

Constructed between 1881 and 1885, this convent in southern Cebu showcases Escondrillas’s “military-monastic” style. The structure is a large Bahay-na-Bato esque structure built of large coral stone blocks for the first floor and Philippine hardwoods for the second floor.

5. The Belltower of San Gregorio Magno (Ginatilan, Cebu)

In the quiet town of Ginatilan, the belltower attributed to Escondrillas’s oversight serves as a vertical extension of state and religious authority which had its plans submitted in the year 1880. He has paid 120 pesos for the work of designing the belltower.

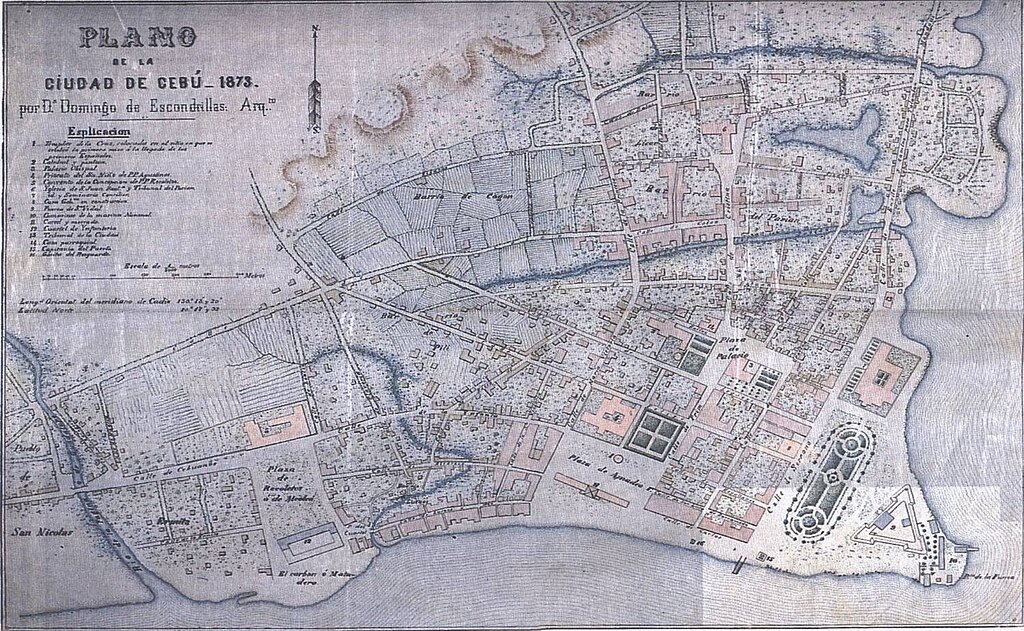

Perhaps his most surprising contribution was not a building at all. In 1873, the same year he drafted the Plano de la Ciudad de Cebú (a vital cartographic document of the city’s urban morphology), Escondrillas established the first printing press in Cebu. Breaking the Manila monopoly on information, the Imprenta de Escondrillas allowed for the local mass production of government notices and religious novenas. He did not just build the bridges to transport goods; he built the infrastructure to transport ideas, laying the groundwork for Cebuano journalism. His legacy is one of resilience. His jail has become a museum; his church, though fallen, remains the soul of Loon; and his maps still guide us in understanding the lost coastlines of our city. He was the agent of the Obras Públicas, though much of his life has been unknown to us, perhaps there is time to appreciate his contributions in this day – the contributions of Don Domingo De Escondrillas y Yarza.

Sources:

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R., and Louella Eslao-Alix, et al. Balaanong Bahandi: Sacred Treasures of the Archdiocese of Cebu. Cebu City: Cathedral Museum of Cebu, Inc. and University of San Carlos Press, 2010.

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R., and Ino Manalo, editors. Integración / Internación: The Urbanization of Cebu in Archival Records of the Spanish Colonial Period. Cebu City (and Manila): University of San Carlos Press and National Archives of the Philippines, 2017.

Fenner, Bruce Leonard. Cebu Under the Spanish Flag, 1521–1896: An Economic-Social History. Cebu City: San Carlos Publications, University of San Carlos, 1985.