Stepping into the town of Lazi on the southern edge of Siquijor, one is immediately arrested by a sense of scale that seems almost out of place in such a tranquil, provincial setting. Here, amidst the whispering acacia trees and the humid breeze of the Mindanao Sea, stands the San Isidro Labrador Convent, a structure that feels less like a parish house and more like a sleeping giant of the Spanish colonial era. Known universally as the Lazi Convent, this massive edifice is not merely a remnant of the 19th century; it is a sprawling “Fortress of Faith” that anchors the identity of the “Island of Fire.” Completed in 1891 under the meticulous supervision of the Augustinian Recollect Fray Toribio Sánchez, the convent was designed to be a sanctuary within a sanctuary. It wasn’t built solely for the local parish priest but was envisioned as a grand rest and recreation house for friars from across the Visayas—a place where the weary missionaries could find physical and spiritual recuperation. As you stand before its weathered coral stone walls, you are looking at what is frequently cited as the largest convent in Asia (though this is still very much up to debate and should be taken with a grain of salt. )

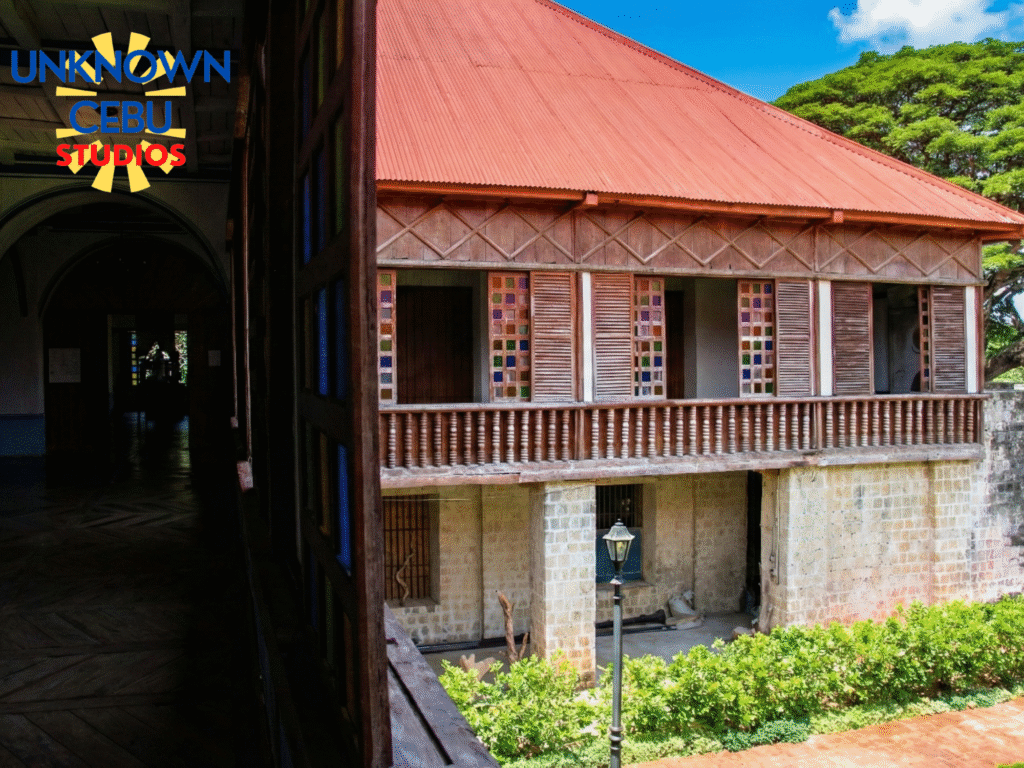

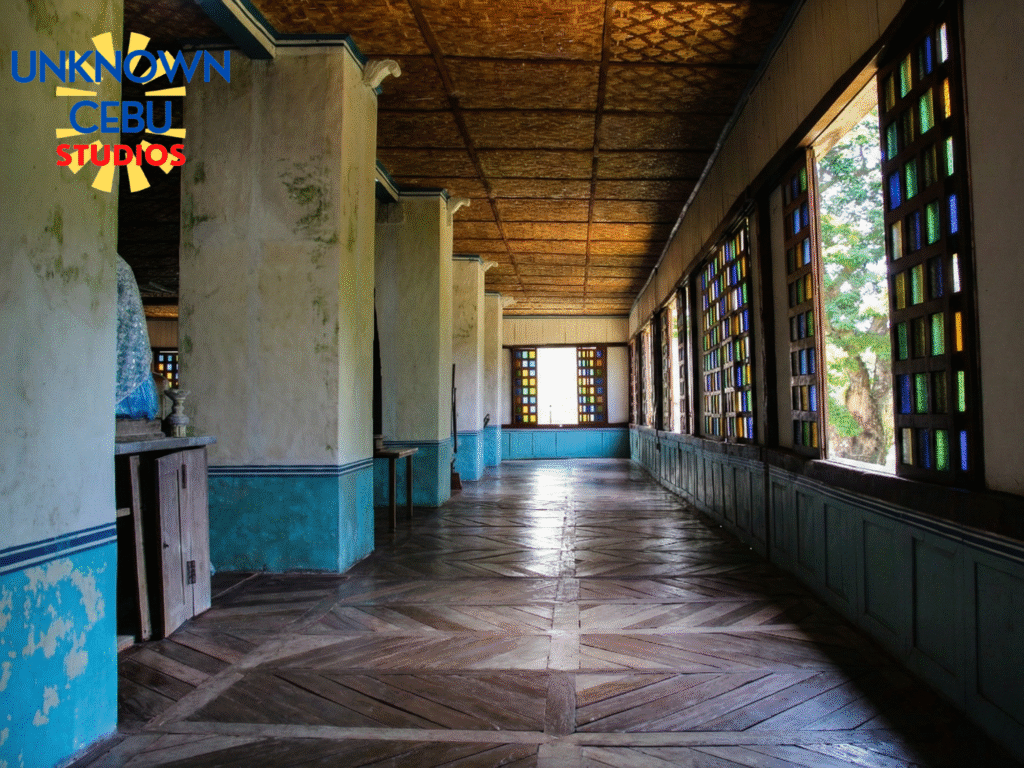

To understand the soul of this building, you must look closely at its bones, which are a masterclass in the Bahay na Bato architectural typology. The structure is a harmonious marriage of sea and forest, grounded by a silong (ground floor) composed of thick coral stone blocks, or tabilla, quarried from the island’s reefs. These meter-thick walls, bound by traditional lime mortar, provide the thermal inertia needed to combat the tropical heat, creating a cool, cavernous zaguan that once housed carriages and livestock. But the true marvel lies above, where the stone gives way to a magnificent upper story constructed from the legendary hardwoods of the Philippines. The structural integrity relies on massive haligues (posts) of Tugas (Molave), the “Queen of Philippine Woods,” known for its iron-like density and resistance to time. Siquijor was once called Katugasan or a place where tugas grows. and the convent is a direct product of that abundance. The floorboards, polished by over a century of footsteps, are laid in herringbone patterns of Narra and Molave, gleaming with a dark, lustrous patina that whispers stories of the friars, revolutionaries, and townsfolk who have walked these halls.

The sensory experience of the Lazi Convent is defined by its mastery of passive cooling and light, an architectural necessity in the sweltering tropics. The upper level is wrapped in a continuous gallery featuring oversized sliding windows made of capiz shells. These translucent shells do not merely block the harsh sun; they diffuse it, bathing the cavernous interiors in a soft, ethereal glow that seems to suspend time. Below the broad windowsills are the ventanillas, small shuttered openings protected by iron grilles, which allow the cool trade winds to sweep across the floor, circulating air through the vast caida (receiving hall) and the private cells. Walking through the U-shaped corridor that embraces the rear courtyard, you can almost hear the rustle of habits and the low hum of Latin prayers. It is a space designed for contemplation, where the architecture itself breathes, expanding and contracting with the heat of the day, proving that the colonial builders understood the environment intimately.

Today, the upper floor serves as the Siquijor Heritage Museum, a custodian of the island’s tangible memory that transcends mere architectural appreciation. The cavernous rooms, once private friar cells, now display a poignant collection of religious statuary, liturgical vestments, and dusty archival documents. Among the most evocative artifacts are the birth and death registers bound in carabao hide—durable, rugged books that contain the genealogy of thousands of Siquijornons. There is a specific, “musty” scent here—the smell of old wood, aging paper, and history—that creates a visceral connection to the past. It is a “living” museum in the truest sense; it hasn’t been sterilized into a modern gallery but retains the creaks and shadows of the 19th century. However, this treasure trove faces the constant threat of the tropical maritime climate, where humidity and salt air wage a slow war against paper and textile, making the recent restoration efforts by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines critical for its survival.

Yet, the Lazi Convent exists at a crossroads between the sacred and the supernatural, sitting comfortably within Siquijor’s dual reputation for Catholic piety and indigenous mysticism. The Spanish named the island Isla del Fuego for the fireflies that swarmed the molave trees—the same trees used to build this convent—which locals believed were the dwelling places of spirits. The sheer size of the convent is often interpreted by folklore scholars as a form of psychological architecture, a massive stone assertion of power designed to awe a population steeped in the traditions of mambabarang (sorcerers) and mananambal (healers). There is even a persistent legend of the Tayog-tayog, a phantom ship that appears off the coast of Lazi in the dead of night, emitting lights and sounds that shake the ground. Some say this ghost ship is linked to the spiritual energy of the convent, a convergence of the colonial fear of Moro raiders and the enduring belief in the engkantos of the island.

Ultimately, the Lazi Convent is more than a candidate for the UNESCO World Heritage List; it is the beating heart of Lazi’s heritage. As you leave the complex, passing through the natural tunnel formed by the ancient Acacia trees that separate the convent from the San Isidro Labrador Church, you realize that this structure bridges the gap between the past and the present. The ground floor, once a stable, now often echoes with the laughter of children in learning spaces, symbolizing a transition from colonial servitude to modern education. It stands as a survivor of revolutions, wars, and typhoons, a massive timber-and-stone vessel that has carried the story of Siquijor through time. It is a place where the walls talk, where the floorboards remember, and where the silence is heavy with the weight of history.

|UnknownCebu|

Sources:

(I’ll update this soon once I get them all together.)

“Lazi Church to be included in UNESCO’s heritage list.” The Freeman (Philstar.com), July 1, 2014. philstar.com/the-freeman/region/2014/07/01/1341170/lazi-church-be-included-unescos-heritage-list.

“The Lazi Church and Convent: National Cultural Treasure.” Negros Season of Culture, November 2025. negrosseasonofculture.com/2025/11/the-lazi-church-and-convent-national.html.

“Siquijor: A Hidden Paradizzze in the Philippines: The Final Part: The Lazi Church.” Tanghal Kultura, November 18, 2022. tanghal-kultura.org/2022/11/18/siquijor-a-hidden-paradizzze-in-the-philippines-the-final-part-the-lazi-church/.

“Lazi Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified December 2, 2025. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazi_Church.

“Vitex parviflora.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 28, 2025. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitex_parviflora.

“Fortifications of the Visayas.” Muog (blog), January 24, 2008. muog.wordpress.com/2008/01/24/fortifications-of-the-visayas/.

“Siquijor: The Lazi Convent.” Lakad Pilipinas (blog), June 2012. lakadpilipinas.com/2012/06/siquijor-lazi-convent.html.

“National Cultural Treasure Series: San Isidro Labrador Parish Church (Lazi, Siquijor).” Loyd’s Travel Trail (blog), February 2016. loydtraveltrail.blogspot.com/2016/02/national-cultural-treasure-series-san_4.html.

“Lazi Church: Timeless Treasure of Siquijor.” Fab Asian Lifestyle. Accessed December 6, 2025. fabasianlifestyle.com/lazi-church-timeless-treasure-of-siquijor/.

“Restoration of Barasoain Church.” Historic Preservation Documents (blog), May 2019. historicpreservationdocuments.blogspot.com/2019/05/restoration-of-barasoain-church.html.

“Lazi Convent & San Isidro Church Siquijor.” Secure Adventures. Accessed December 6, 2025. secureadventures.com/lazi-convent-san-isidro-church-siquijor/.

“Isla del Fuego: Siquijor.” Ever Somewhere (blog), January 31, 2019. eversomewhere.wordpress.com/2019/01/31/isla-del-fuego-siquijor/.

“Lazi Church and Convent.” Jay Darryl (blog), March 9, 2012. jaydarryl.wordpress.com/2012/03/09/lazi-church-and-convent-3/.

“Phil Churches.” Scribd. Accessed December 6, 2025. scribd.com/document/238495961/Phil-Churches.

“Lazi Convent.” Wanderlog. Accessed December 6, 2025. wanderlog.com/place/details/5811672/lazi-convent.

“Siquijor.” Evendo. Accessed December 6, 2025. evendo.com/locations/philippines/siquijor.