If you’ve ever travelled the coast road of Baclayon, Bohol, chances are your eyes have been drawn to the stately mansions standing guard over the Visayan Sea. But few possess the sheer scale and storied soul of the Malon House. This imposing structure, dating back to a time before the turn of the 20th century, isn’t just an old house; it’s the veritable matriarch of Baclayon’s ancestral homes, proudly holding the title of the largest among them. Estimated to have been erected sometime between 1876 and 1886, it is a tangible chronicle of the town’s history, a silent witness to eras of trade, power, and fierce cultural pride. Today, the house remains the cherished domain of the prominent Malon family’s sixth generation, each floorboard whispering tales of their enduring legacy. To step across its threshold is to take a fifty-meter journey down the road of time and find yourself rooted firmly in the late nineteenth century.

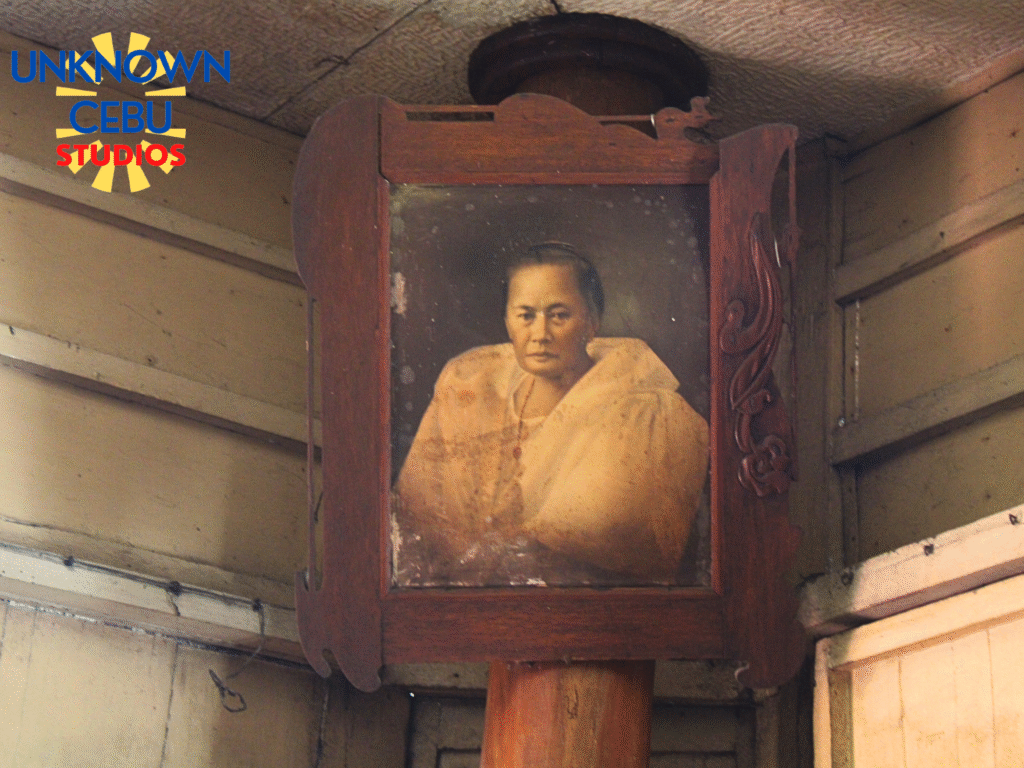

The Malon lineage of this home finds its definitive beginning in the formidable figure of Doña Ambrosia Ypong de Malon (1823-1908), a wealthy merchant whose success laid the foundation for this architectural grandeur. The house itself soon evolved from a symbol of commercial success to a discreet center of regional power. Under the ownership of Juan Malon, who dedicated his life to service at the Baclayon Municipal Hall, the residence became an unofficial political headquarters. Imagine the humid evenings when shadows gathered, and the grand halls played host to hushed, yet consequential, meetings with Bohol’s own native son: the future Philippine President Carlos P. Garcia. For decades, this dwelling has stood not only as a family residence but as a silent, powerful stage where the destiny of a town, and perhaps a nation, was quietly discussed and charted.

From an architectural standpoint, the Malon House is a fascinating study in late Spanish Colonial adaptation, built in what historians describe as the elegant “Geometric Style.” The exterior is distinguished by complex geometric ornaments gracing its wall panels and transoms. It shares the familiar grace of its neighbours, like the Villamor House, with its sturdy chamfered corners, a design element that speaks to both stability and style. Yet, the Malon House possesses features truly unique in Boholano architecture. Most striking is the continuous, sweeping band of barandillas—traditional wooden railings—that doesn’t merely cover the ventanillas (small grilled windows) but boldly wraps itself around the entire house, unifying the façade. Equally unusual is the set of double-paned windows on the upper floor, where the familiar sliding capiz windows are mounted on the exterior of the façade, not the interior—a reversal of the common norm. This exterior placement, coupled with fixed persianas in-between, strongly suggests a significant remodeling during the nascent American Era, updating the home to fit the new style en vogue of the time.

Like any structure that has weathered over a century, the Malon House bears the scars of its long life. Originally designed in a sweeping T-shape, it suffered a serious blow in 1968 when a powerful typhoon tore through, destroying the crucial wing that faced the sea. This forced the first major modern alterations: the original nipa roof was necessarily replaced with G.I. sheets, and the exquisite coffered ceiling succumbed to damage and was regrettably replaced with plywood. The ground floor, too, saw change, rebuilt in concrete, though the street façade retained its blended wooden boards. The house’s dignity faced another, more insidious challenge during a major road-widening project. The new highway, passing directly in front, was unforgivably raised by one meter, drastically reducing the perceived height of the ground floor façade and leading to the chronic issue of rainwater seepage—a modern violation of a historical masterpiece.

The modern encroachment, however, ignited a powerful flame of local defiance. When the Korean contractor Hanjin threatened the street façade with partial demolition, the owners did the unthinkable: they refused the compensation offered. Their refusal was not a solitary act; together with other Baclayon ancestral homeowners affected by the same project, they launched a tireless, arduous, and ultimately successful fight. This struggle—the first of its kind in Bohol, where citizens mobilized to protect their tangible history—led directly to the founding of BAHANDI, the Baclayon Ancestral Homeowners Association. Registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, this self-help initiative is dedicated entirely to the preservation of Baclayon’s precious cultural and architectural heritage, transforming a moment of crisis into a lasting institutional triumph.

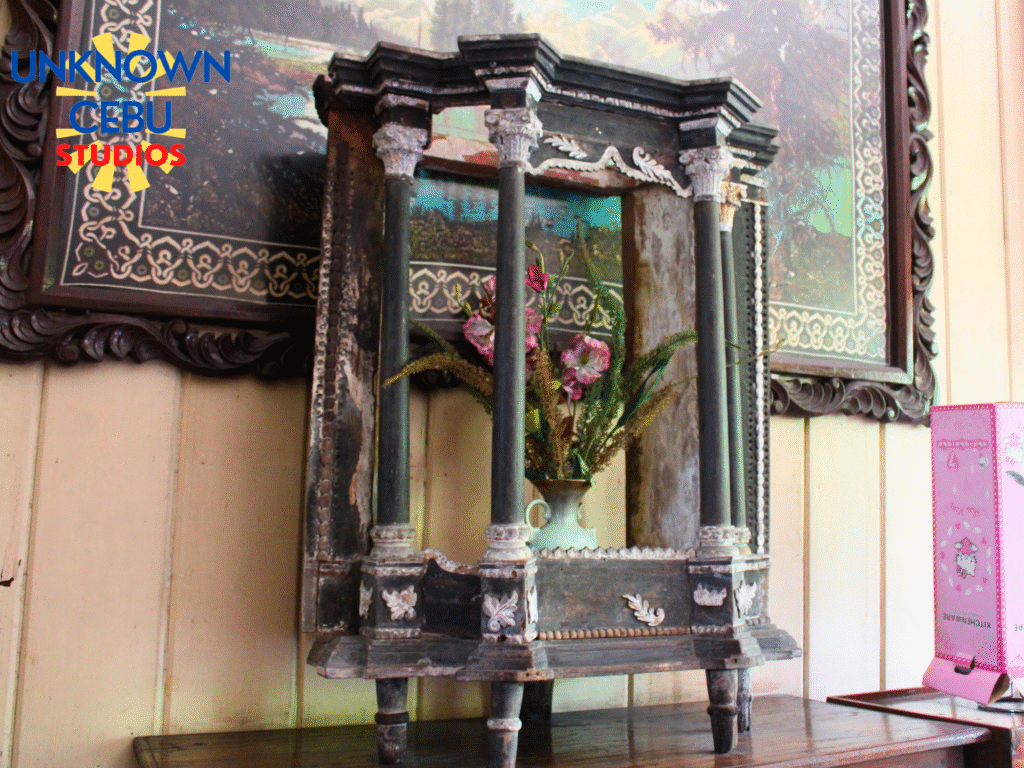

The success of their struggle means that the Malon House today stands excellently preserved, offering a spectacular glimpse into the opulence and devotion of the past. Visitors are welcomed by a magnificent grand staircase that ascends to an upper floor teeming with a multitude of antique period furniture and housewares—a genuine, curated museum of everyday life. It also carries a deep spiritual significance, proudly serving as the home for the statue of Saint John, which takes center stage during the sacred observance of Semana Santa (Holy Week). The Malon House is now accessible as a museum that can be visited upon request, and even offers home-stay accommodations for travelers—a unique “bed and breakfast” experience. To stay here is not just to book a room; it’s to participate in the ongoing history of the Malon family and the enduring, unbreakable spirit of Boholano heritage.

|UnknownCebuStudios|

Sources:

Akpedonu, Erik, and Czarina Saloma. Casa Boholana: Vintage Houses of Bohol. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2011.

Jay, Al. Interview by Anonymous. June 2022.

“Revisiting the Past: Bohol’s Ancestral Houses.” Around Bohol. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.aroundbohol.com/revisiting-the-past-bohols-ancestral-houses/.

“Baclayon Ancestral Houses.” Bohol.ph. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.bohol.ph/article102.html?sid=a7ec2413791210a0ea2747eb7ff4831e.

Pinoyborian. “Baclayon: Malon House.” Visit BOHOL. April 2012. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://visit-bohol.blogspot.com/2012/04/baclayon-malon-house.html.

“Malon House Home Stay (Baclayon).” Bohol.ph. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.bohol.ph/resort.php?businessid=367.

“Baclayon Church Heritage Architecture.” Bohol-Philippines.com. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://bohol-philippines.com/baclayon-church-heritage-architecture/.

GypsySoul73. “Treasures from the Past.” GypsySoul73. April 2008. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://gypsysoul73.blogspot.com/2008/04/treasures-from-past.html.

Old Bohol (Facebook page). “Malon Ancestral House Circa 1880s, Baclayon, Bohol. Photo courtesy of Joachim Camba.” Facebook, March 8, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/oldbohol/posts/malon-ancestral-house-circa-1880s-baclayon-bohol-photo-courtesy-of-joachim-camba/2385174378248357/.

100082156554812 (Facebook user). “Post about Malon House.” Facebook, March 14, 2023. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/100082156554812/posts/295854667150788/.