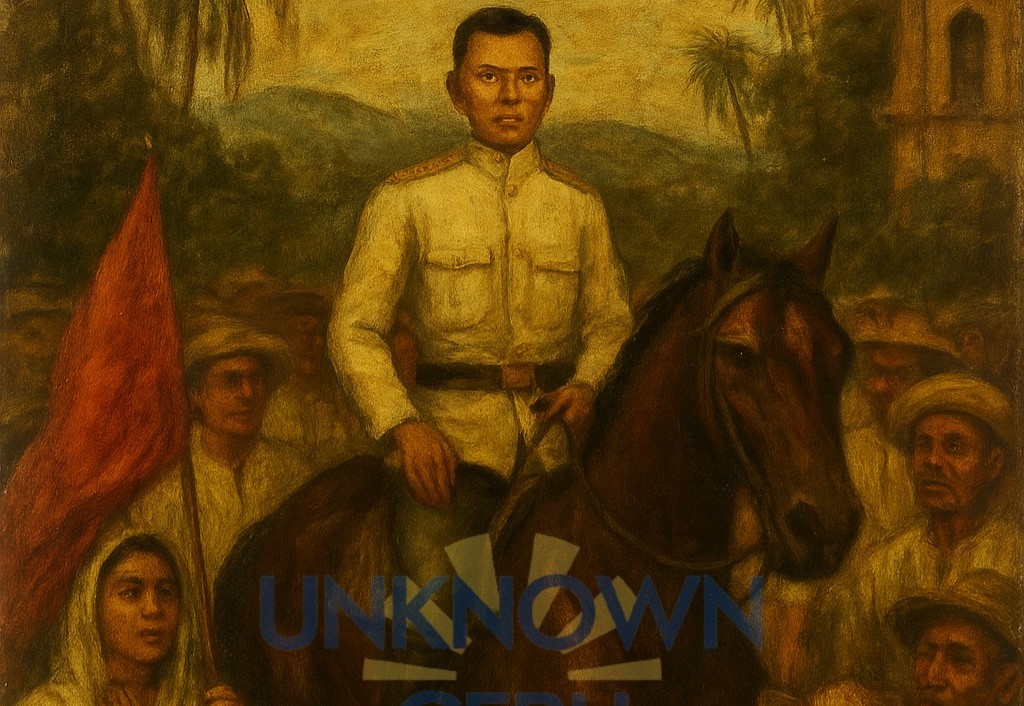

Leon Kilat, born Pantaleon Villegas, played a pivotal role in the Cebuano chapter of the Philippine Revolution. By mid-1897, the revolution that had begun in Manila had spread to the Visayas. In Cebu, a Katipunan chapter emerged among the laborers of San Nicolás with the backing of the local ilustrado elite. To lead the movement, the Manila Katipunan sent Leon Kilat, a charismatic 24-year-old revolutionary from Negros Oriental who had lived in both Cebu and Manila. Arriving in early 1898, Kilat’s presence coincided with Spanish authorities intensifying their crackdown on suspected rebels. With several local Katipuneros arrested, Kilat and his allies decided to expedite their plans, initially scheduling an uprising for Good Friday, April 8, 1898, when colonial troops would be unarmed during religious rites.

However, the actual uprising erupted earlier, on April 3, Palm Sunday, in what became known as the Battle of Tres de Abril. Around 300 Katipuneros launched a surprise assault on Spanish forces in San Nicolás. Armed mostly with bolos and spears, they overwhelmed the local garrison and forced the Spanish, along with their families, to take refuge in Fort San Pedro. For a brief moment, the Katipuneros held control of parts of Cebu City, even renaming a plaza in Kilat’s honor. |UnknownCebu| Yet, Spanish reinforcements quickly arrived from Manila, outmatching the poorly armed rebels. Facing superior firepower, Kilat and his men were forced to retreat southward. On April 7, Holy Thursday, Kilat led his group to the town of Carcar, about 20–30 kilometers away, where they hoped to regroup.

Upon arrival in Carcar, Kilat was received as a hero by the local elite, or principalia. He was initially hosted by Capitan Simeon Paraz and later stayed in the house of ex-Capitan Timoteo “Tiyoy” Barcenilla. The town’s leaders, including current Capitan Municipal Florencio “Inciong” Noel, met with Kilat and urged him not to engage Spanish forces in Carcar’s poblacion to avoid destruction. Kilat, however, refused, insisting he would face the Spanish head-on rather than retreat into the mountains.

That night, the town’s elite, fearing Spanish reprisals and prompted by a purported warning from Father Francisco Blanco during a church confession, secretly convened to discuss Kilat’s fate. According to the 1925 account of Vicente Alcoseba, Capitan Noel took the lead in organizing a conspiracy to kill Kilat. Other conspirators included ex-Capitanes Barcenilla, Paraz, Leocadio Jaen, Jacinto Velez, and Kilat’s own aide-de-camp, Apolinario Alcuitas. The priest’s alleged warning—that Spain would inflict a “juez de cuchillo” translated to something such as ” on Carcar if Kilat remained—was never corroborated by official Spanish records and remains a debated point among historians.

In the early hours of Good Friday, April 8, 1898, Kilat was asleep at Barcenilla’s home when the conspirators struck. Vicente Paraz, the son of Capitan Paraz, reportedly witnessed Capitan Noel ascend the stairs holding a crucifix and shouting “¡Viva España!” Inside Kilat’s room, multiple men stabbed the sleeping revolutionary repeatedly. His skull was later smashed with the butt of his own Mauser rifle. To test the power of Kilat’s rumored amulets, the conspirators further mutilated his corpse after death. His body was publicly displayed in the town plaza before being quietly buried.

In the aftermath, the town’s leaders believed they had averted a Spanish massacre. Florencio Noel was later elected town jefe under the revolutionary government in 1899, and Carcar’s main plaza was renamed Plaza Leon Kilat in 1926. Yet, the betrayal tarnished the reputation of the conspirators. |UnknownCebu| In the 1920s, local elder Vicente Rama invoked Kilat’s murder in political disputes against the Noel clan. As decades passed, a mix of legend and oral tradition added complexity to the story.

Modern historians stress that most details about Kilat’s death come from Alcoseba’s account and local lore, not from Spanish documentation. Stories such as the priest’s warning and the testing of amulets reflect myth-making rather than confirmed fact. Apolinario Alcuitas’s role is especially controversial: some see him as a traitor, others as someone who acted under duress to protect his town. Meanwhile, unsubstantiated claims linking the Cuenco family to the event have been largely dismissed by scholars. Despite the uncertainties, what remains clear is that Kilat’s assassination marked a tragic turning point in Cebu’s revolutionary history, and his legacy endures as both martyr and folk hero.

|UnknownCebu| DO NOT REPOST | Sources in Comments

Note: Should any corrections or clarifications be raised, you are welcome to message us directly.

Sources and Further Readings

Wikipedia contributors. “Leon Kilat.” Wikipedia, June 2025.

Wikipedia contributors. “Battle of Tres de Abril.” Wikipedia, May 2025.

Bersales, Jobers. “Kilat’s Death and the Cuenco-Noel Controversy.” Inquirer.net

, April 8, 2017.

Mansueto, Trizer D. “Leon Kilat: Non-Cebuano Led 1898 Cebu Revolt vs Spain.” Cebu Daily News, April 5, 2013.

Philippine Daily Inquirer. “Leon Kilat Non Cebuano Led 1898 Cebu Revolt vs Spain.” April 5, 2013. Republished on Cebu Daily News.

SunStar Cebu. “Was the Man Who Killed Leon Kilat a Hero or a Villain?” April 5, 2017.

Philippine Canadian News. “Apolinario Alcuitas – The Man Who Killed Leon Kilat.” PhilippineCanadianNews.com

, April 23, 2016.

Artes de las Filipinas. “Leon Kilat and His Assassination.” Accessed June 2025.

Carcar Families. “The Carcar Assassination of Leon Kilat.” Genealogy Blog, August 13, 2009.