It was the month of May in the year 1815 on the Island of Cebu, Visayas Region, Central Philippines. Enter the town of Tinaan, modern-day Naga City on the south-eastern coast of the island, where a man rallies members of his town to march on the city against a common adversary. This man, together with his allies, had enough of the rich men of the city bearing down to claim lands that, in their eyes, were theirs as they had been for many years. These men would rally and then begin the twenty-kilometer march towards the center of government in Cebu City, where in their eyes the wealthy men who threatened their livelihoods, along with fellow locals, were based, and the place where they may have their grievances heard or, if not, a less amiable solution. Far down south in the town of Boljoon, another man who was hard at work himself organizing a defense for the Cebuano people against Moro pirates together with his competent native Commanders heard of this. On one of those fateful days in the year 1815 was born a story that would be a hallmark of the struggle of Filipinos rising up to defend their own interests and the involvement of a peculiar Spanish priest who was assigned a long way south from the site of the conflict; the priest who will be later called a Warrior-Priest. This is the story of Juan Diyong and Fray Julian Bermejo in their respective roles during the 1815 “Insurrection” in Cebu.

An unspecified time before the start of the Uprising of 1815, grievances against two specific land-owning Chinese mestizos in Cebu City came to occupy the thoughts of several communities in the south of Cebu. These two Chinese Mestizos were named Don Blas Valle Crisistomo, otherwise known as Dato Blas, and Don Gavino Rosales, who resided in the Pari-an district of the city, where most of the wealthy Chinese were cobbled together into one community. They had a need for grazing areas and chose land in San Fernando and Naga as places where the large herds of Cows, carabaos, and other large animals may graze, leading to ire from the locals, who had to contend with the increasing number of animals that challenged their own in addition to the loss of grazing areas that were essential to their livelihood. In the eyes of some who lived in the affected areas, this was no more than a land grab perpetrated by some wealthy men in the city who had no interest in earning profit as they had done before, though to most all they wanted was to simply protect their land. In the eyes of the two Chinese mestizos, however, they were doing absolutely nothing wrong, as the Spanish authorities had given them the license to use the then-contested land for grazing in order to supply food to the city. Both sides had valid arguments that could be the basis for some sort of legal arbitration.

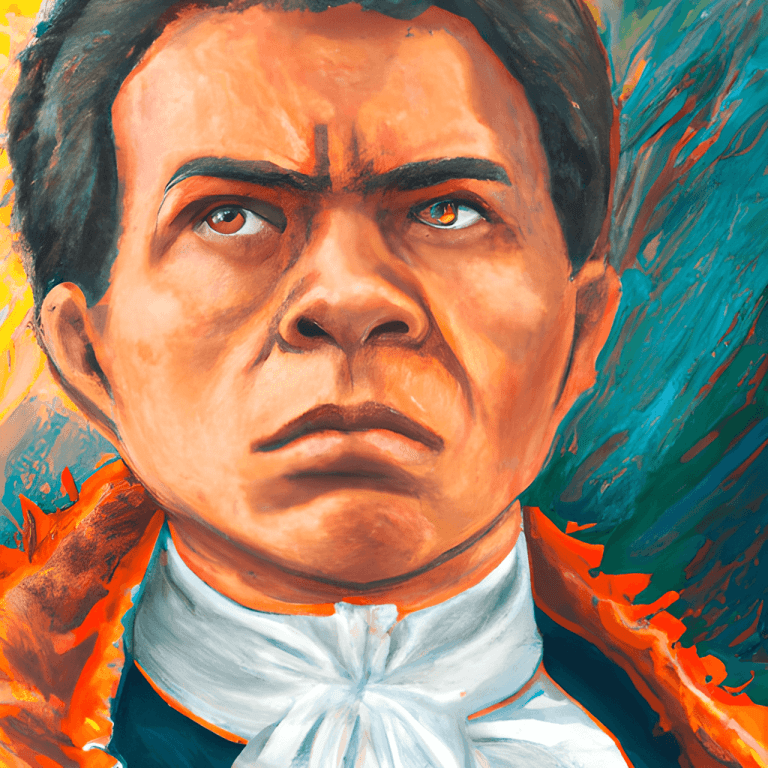

At this juncture enters one of the main characters of this story, the elusive figure who has been called “The Founder of San Fernando”, a man named Juan Diyong. Juan Diyong is shrouded in mystery, but this much is clear about his life: He came to Cebu from the town of Tubigon in Bohol, crossing the Cebu Strait to settle in Sangat, San Fernando, and there he would work as a humble farmer for some time. It should be noted that at this particular time of the uprising, he was listed as being a resident of Tinaan, Naga. Upon learning of the predicament of the people, he and a large number of others marched on the city in protest at what, in their eyes, seemed an illegitimate use of land that was rightfully theirs. They were armed with weapons such as Bolos and other primitive arms; it is worth noting that they did not carry firearms during their march. As the group marched further north from Tinaan to Naga’s Poblacion and then on to other smaller Barangays, they further gained support and, more importantly, supporters who sympathized with Juan Diyong.

Even though a number of marchers were clamoring for an audience with the governor of Cebu at the time, [, he did not appear before the people to address their concerns for one reason or another. This caused some anger among the marchers, but no matter. They tried to get in contact with the two Chinese mestizo businessmen, Blas and Gavino Reynes, to no avail. Tired of having to chase those who wronged them, the marchers turned on the nearby Fort San Pedro. Following a short confrontation, a number of marchers were able to seize the Spanish fort for themselves for a short while, taking arms and a bronze cannon, which they would put to good use. The marchers directed their anger towards the Casa de Gobierno, otherwise known as the Casa Real, right across the street, pointing the bronze cannon in the direction of the building. It was a clear threat that if the demands of the people were not met, the city could very well be without its provincial capitol. After a short while, it seemed that the marchers simply left the area, taking with them the captured arms and marching back to the south in victory. Somehow, even though Fort San Pedro was besieged by an angry mob and even though they had been marching through the streets trying to find those who would listen to them, no casualties on either side were reported. This march and its subsequent withdrawal back to the south had mixed results for the marchers.

For one, they had gotten the point across that the land was not only theirs but also that they did not relish the idea of having some businessmen ruin it. Other than that, it was apparent to the authorities that further action would be required in order to solve this issue. Time passed, and the Governor of Cebu sent a force under the command of a certain Leon Santiago to arrest those who had participated in the march on the city. The punitive force meant to capture Juan Diyong and his companions did not materialize after insubordination on the part of the people of San Nicolas. Another group meant to arrest Juan Diyong was led by a certain Mariano Rafols to investigate, but upon their arrival, they were met by a priest who became involved in the matter, this priest being Fray Julian Bermejo. Fr. Bermejo’s involvement in this event would extend even farther than just mediation, as Governor Andrade was enraged at the intervention and would make accusations against Fr. Bermejo and another Augustinian priest and even included the Bishop of Cebu in his furious tyrade. Fr. Bermejo was accused by Governor Andrade of harboring fugitives by protecting the marchers who besieged the city.

Fray Julian Bermejo Horabuena, O.S.A., had heard of the commotion in the city through Pedro Cabanlit, one of his Barangay Commanders, and was in contact with the perpetrators of the march along with a fellow Augustinian priest. Mariano Rafols was known to have been in contact with Fray Julian Bermejo and on several occasions discussed the matter with the priest; the fruit of the meeting was an assurance that the matter had been settled and there was no longer any need for further investigation. Fr. Bermejo was respected among the locals, as years before he had developed a system wherein groups of native ships called Barangay were to assemble and then intercept any Moro pirate that crossed their path. In 1815, during the battle of Sumilon, a fleet under the command of his local officers but still under the direct command of Fr. Bermejo had smashed a pirate fleet under the command of pirate Warlord Orandin/Gorandeng off the coast of Sumilon Island. This victory earned him prestige among the people and would give him the title of a warrior priest; his officers too were praised for their bravery on the seas. The accusations presented against him and his fellow priests by the Governor of Cebu became a source of controversy and tension. This would lead to a report sent by Fr. Bermejo to the authorities in Manila, explaining the situation.

Fray Julian Bermejo was in command of some 300 troops, who were called “Hombres Armados” meaning armed men”, and were primarily in service to fight off the many Moro raids of the time. This was dubbed the great “Christian” Army,” according to an Augustinian priest, Fray Fabian Rodriguez, who served in Boljoon many years after the death of Fr. Bermejo. Interestingly, a theory posed by the renowned Michael Cullinane, Associate Director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies and a Teaching Faculty member in the Department of History, proposes a direct link between Bermejo and Juan Diyong. Among the tales that surround the near-legendary character of Juan Diyong is one that says he was a great warrior who achieved great success in battle against his foes. It is proposed that Juan Diyong, aside from being a leader in the 1815 uprising and the previously mentioned march, was a commander, or at the very least, a very skilled warrior, among the so-called “Christian Army” of Fr. Julian Bermejo. This connection would explain his active involvement in negotiations since, if we treat the theory as true, it would give him even more reason to defend the natives, as he is not only protecting their rights but also the freedom of one of his most renowned fighters.

Following the events of May and another less significant march in August, a solution was reached between all parties concerned. Fr. Bermejo was a primary figure in the negotiations, which led to the moving of all grazing livestock from the disputed lands to Carcar farther south to avoid any more confrontation. For his part, he risked his own integrity and reputation in a direct conflict with the Governor that could have resulted in his removal as Parish priest of Boljoon. It all ended well for all parties involved, with the natives getting the used land returned along with the prevention of further hostilities that may lead to a wider-scale rebellion. Fray Julian Bermejo would continue his tenure as the Parish Priest of Boljoon having defused the situation.

Possibly, according to some, about three decades after the uprising of 1815 in 1858. Juan Diyong would organize the barrios of Magsico, Cabatbatan, Balungag, Sangat, Panadtaran, and Pitalo for the purpose of having a singular movement to convince Spanish authorities that a new town should be made and separated from Naga leading founding of the modern day town of San Fernando. He would succeed in this endeavor and would be hailed as the town’s founder making him one of the unknown, yet influential persons in Cebuano history. His uprising has frequently been framed today as a black and white polarized issue regarding the Filipino desire to be free from Spanish rule, but it is much more complicated than that; it is up to the reader to decide.

Sources: https://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/133289/remembering-juan-diyong

Sources:Cullinane, M. (2016). A Time Between Times: Situating the 1815 Uprising in Cebu. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 44(3/4), 211–300. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26788414

Sources:https://archive.cebuanostudiescenter.com/bag-ong-kusog-april-1923/

Sources:El «Padre Capitán» Julián Bermejo y la defensa contra la piratería mora en Cebu

One comment on “The Saga of Fray Julian Bermejo Part 4: The 1815 Uprising of Juan Diyong”