The southern littoral of Cebu possesses a deceptive tranquility, particularly along the Tañon Strait in Malabuyoc. Observing the silhouette of Negros Island across the channel, one might appreciate the scenic geography, yet a historical analysis reveals this strait was less a picturesque boundary and more a strategic chokepoint. The calm, cerulean waters masked a volatile maritime corridor utilized for centuries as a primary route for predation rather than mere travel. To fully comprehend the significance of the stone sentinel situated here is the Malabuyoc watchtower. One must deconstruct the romanticized view and recognize the horizon as a vulnerable frontier. Amidst the limestone topography, this watchtower stands not merely as a ruin, but as a calculated fortification, a surviving element of a grand defensive design of the Malabuyoc Baluarte.

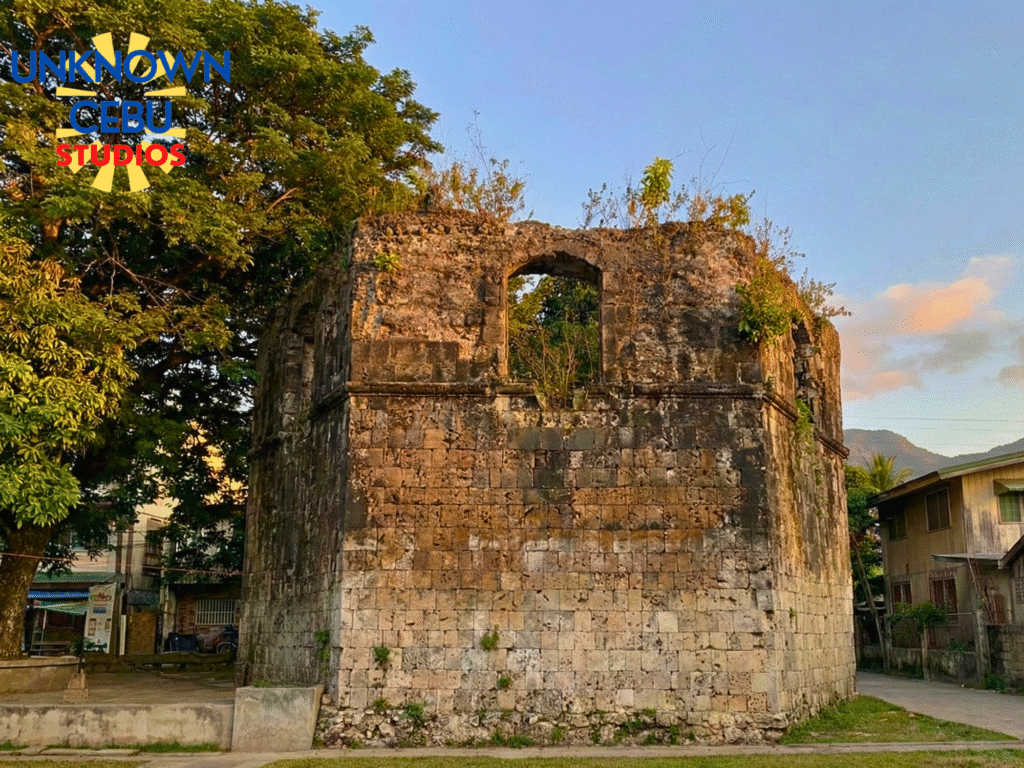

The tower, built probably in the early 19th century (making it predate the current church), is a mark on the map. Contemporary observers often struggle to contextualize the pervasive anxiety that characterized the Visayas during the prevalence of the southwest monsoon, or Habagat. This climatological window facilitated the arrival of maritime raiders, a period historically associated with the “Moro Wars.” For the coastal settlements of the 18th and 19th centuries, this was an existential struggle for territorial and demographic survival. The devastating raids of 1754, often cited in historical records as a year of profound terror, saw entire visitas and towns depopulated, their inhabitants seized by pancos (fast raiding boats) for the slave markets of the south. The etymology of Malabuyoc which is derived from buyoc, implying fruit trees bending with abundance,suggests a prosperous locality that required rigorous defense. The Baluarte was a utilitarian necessity; its existence serves as a monumental record of an era when ecclesiastical bells signaled imminent danger rather than liturgical calls.

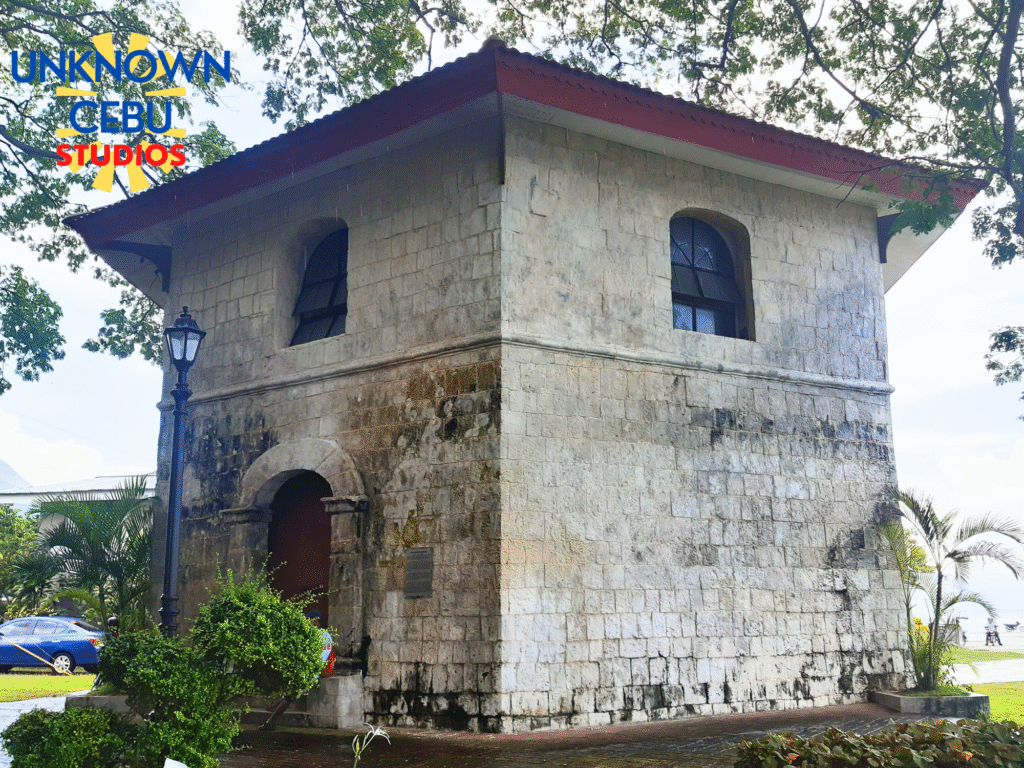

The architecture of this defense is inextricably linked to the military acumen of Fr. Julian Bermejo, the “Padre Capitán.” An analysis of the structure reveals the implementation of his broader defensive doctrine. Recognizing the vulnerability of isolated settlements, Bermejo engineered a cohesive coastal defense grid, effectively a “Great Wall” of coral stone fortifications. The Malabuyoc Baluarte functioned as a pivotal node in his telegrafo system—an ingenious optical communication network. Upon the visual confirmation of a hostile sail by a sentinel in Samboan, smoke or flag signals would relay the alert to Malabuyoc, which would in turn signal Ginatilan, mobilizing the coastline with remarkable speed. The structure’s octagonal planimetry was not merely ornamental; it was a tactical design intended to deflect ballistics and afford the sentinels a panoramic, 360-degree command of the maritime approach.

Architecturally, the structure is a study in vernacular adaptation, constructed primarily of distinct coral stone. There is a functional irony in the material sourcing; the very sea that facilitated the threat provided the masonry for defense. The construction methodology relied on mampostería (rubble masonry) bound by a lime mortar mixture, which oral histories suggest was fortified with organic additives like the sap of the lawat tree or egg whites to enhance durability. However, structural integrity is not absolute. The magnitude 7.2 earthquake of October 15, 2013, compromised this heritage asset, causing significant structural trauma to walls that had weathered centuries of conflict. The subsequent restoration was a meticulous technical process, necessitating the removal of incompatible modern cement interventions and the reapplication of period-correct lime mortar to restore the masonry’s “breathability” and structural coherence.

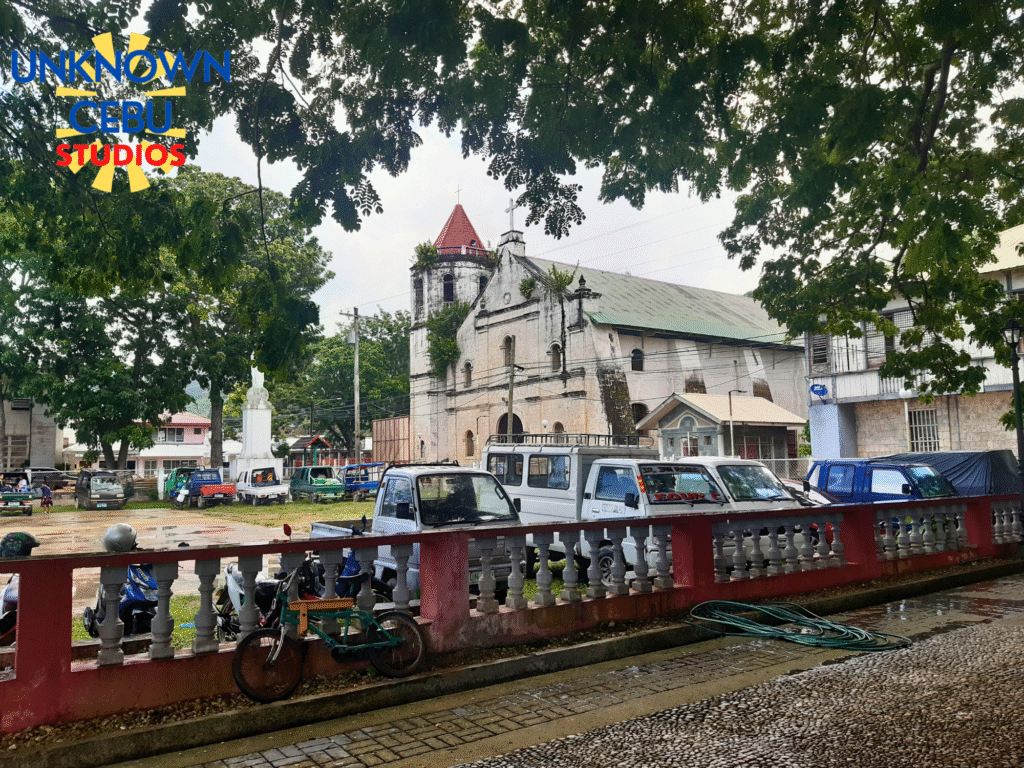

Today, functioning as the Museo de Malabuyoc, the site has transitioned from a martial fortification to a repository of local heritage. The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) restored the watchtower in 2015-2017. The curation moves beyond simple exhibition, attempting to contextualize the “soul” of the municipality. The display of ecclesiastical artifacts establishes the intrinsic link between the fort and the adjacent San Nicolas de Tolentino Church, underscoring the dual role of the Spanish colonial complex as both spiritual and military center. Furthermore, the site acts as a locus for intangible heritage, specifically the folklore surrounding the “Golden Bell.” Whether historically factual or apocryphal, the persistent narrative of the bell being submerged in the strait or buried to prevent looting illustrates the community’s collective memory of trauma and preservation associated with the Malabuyoc Baluarte.

In a comparative architectural analysis, the Malabuyoc watchtower is diminutive relative to the grand fortress of Boljoon and less vertical than the campanario of Samboan, yet it possesses a distinct typological significance. It stands as the symbolic legacy of a Spain that has long gone and a people who have descendents who are alive today because of their ancestors, yet the operational reality was distinctly local. While the sovereign authority resided in Spain, the eyes scanning the horizon and the hands manning the artillery were Cebuano.

Sources:

National Museum of the Philippines. “NATIONAL MUSEUM QMS Manual of the Cultural Properties Regulation Division.” PDF document. Accessed November 30, 2025. nationalmuseum.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/QMS-CPRD-Final-pdf.pdf.

“Simbahan ng Malabuyoc.” NHCP Historic Sites (blog). Published November 11, 2020. nhcphistoricsites.blogspot.com/2020/11/simbahan-ng-malabuyoc.html.

National Commission for Culture and the Arts. “TALAPAMANA Visayas.” Accessed November 30, 2025. talapamana.ncca.gov.ph/index.php/component/content/article/talapamana-visayas?catid=10&Itemid=101.

“Fray Julian Bermejo, OSA “El Padre Capitan” of Boljoon.” Basilica Minore del Sto. Niño de Cebu. Last modified May 31, 2017. santoninodecebubasilica.org/chronicles/fray-julian-bermejo-osa-el-padre-capitan-boljoon/.

Tundag, Cris E. “Historic landmark.” Cebu Daily News, March 27, 2017. cebudailynews.inquirer.net/113407/historic-landmark.

Catubig, Jessa. “The baluartes of Cebu.” Cebu Daily News, June 7, 2017. cebudailynews.inquirer.net/132498/the-baluartes-of-cebu.

Catubig, Jessa. “Malabuyoc top tourist destination closes.” Cebu Daily News, June 2, 2017. cebudailynews.inquirer.net/132006/malabuyoc-top-tourist-destination-closes.

Vios, Jonathan. “Treasures waiting in Malabuyoc.” The Freeman (Philstar.com), October 23, 2016. philstar.com/the-freeman/cebu-lifestyle/2016/10/23/1636019/treasures-waiting-malabuyoc.

Dalizon, Alfred. “Government funds restoration of churches.” INQUIRER.net, October 19, 2014. newsinfo.inquirer.net/645313/government-funds-restoration-of-churches.

“Fr. Julian Bermejo, Oslob.” MyCebu.ph. Accessed November 30, 2025. mycebu.ph/article/fr-julian-bermejo-oslob/.

“Bantayan sa Hari.” Jaydilan.weebly.com (blog). Accessed November 30, 2025. jaydilan.weebly.com/blog/bantayan-sa-hari.

“Malabuyoc.” Wikipedia. Last modified November 28, 2025. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malabuyoc.