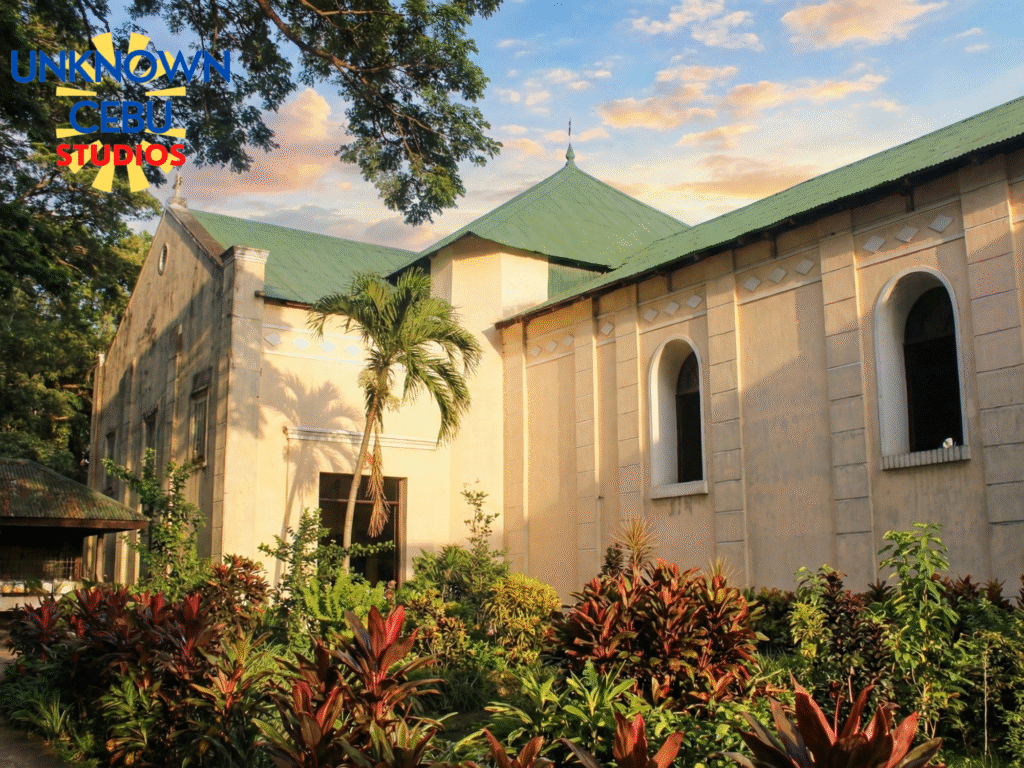

When you travel just eight kilometers south of Dumaguete City, leaving the urban bustle for the coastal breeze of Negros Oriental, you are greeted by a structure that defies the architectural norms of the Visayas. Facing the vast Bohol Sea, the San Agustin Church of Bacong is not merely a place of worship; it is a fortress of history and a National Cultural Treasure that demands your attention. Unlike its contemporaries across Cebu and Bohol, which were almost exclusively built from the abundant gray coral stone, Bacong stands out with a warm, reddish hue as they used relatively large blocks of limestone. This is the enduring legacy of the Augustinian Recollects, specifically Fray Leandro Arrué Agudo, who envisioned a masterpiece that was to be laid down in 1866 with the first mass celebrated by 1883 and broke the mold of the local area by utilizing fired clay bricks. Standing before its facade, you can almost feel the weight of history—this church was oriented towards the east not just for theological symbolism, but for maritime surveillance, acting as a sentinel against the horizon where both trading ships and raiding fleets once sailed.

The church is a fascinating study in what we call “Earthquake Baroque,” but with a distinct material twist that separates it from the usual heritage trail. While the main nave showcases that rare brickwork, signaling a specialized kiln industry in the town during the mid-19th century, the commanding belfry returns to the robust coral stone. Rising as the tallest belfry in Negros Oriental, the structure is definitely imposing. If you look closely at the corners of the tower, you’ll notice a brilliant feat of engineering: L-shaped interlocking masonry which is unique compared to other churches. These monolithic corner bonds were designed to increase shear strength, a necessary innovation in a region prone to seismic tantrums. It is chilling to imagine the days if the ringing of these bells didn’t signal Mass, but to signal war or evacuation.

Stepping inside the cavernous interior, the roar of the highway fades, replaced by a sort of roar of silence that has been preserved since 1865. The focal point is the Retablo Mayor, the oldest altarpiece in the province, intricately carved from the Philippines’ hardest woods, Molave and Yakal. But the true auditory treasure of Bacong lies in the choir loft. Here rests the Roques Hermanos pipe organ, a rare survivor from the year 1894. Commissioned from Zaragoza, Spain, it is one of only three of its kind in the entire archipelago. After falling silent for decades, ravaged by termites and time, it was meticulously restored in 2009. Today, its pipes—reconstructed with a specific tin-lead alloy to match the original acoustic properties—can once again sing the “Bajoncillo” and “Trompeta Batalla,” voicing the same melodies that would have filled this space just before the Spanish empire fell.

However, the walls of this church of San Agustin (not to be confused with the older in Manila) hold memories more volatile than incense and prayer; they hold the sparks of the Philippine Revolution. It is a detail often missed by casual tourists, but this church was the childhood playground of Pantaleón Villegas, the legendary “Leon Kilat.” Born in Bacong in 1873, the man who would eventually lead the historic Battle of Tres de Abril in Cebu began his life here as a humble sacristan. It was within these brick walls and the adjacent convent that the young Villegas likely received the education and discipline that would later transform him into the fearsome “Lightning Lion” of the Katipunan. Standing in the transept, one may ponder what a young Villegas felt—that the very institution representing colonial authority also was a place he was once a part of, the boy who would become its fiercest adversary in the Visayas.

Despite the ravages of World War II, which saw the destruction of so many colonial edifices across the Philippines, Bacong Church miraculously survived relatively intact. This survival ensures that when you run your hand along the rough texture of the walls or look up at the painted friezes, you are touching authentic 19th-century history, not a post-war reconstruction. The church complex, which includes the convent and the nearby Spanish-era Tindoc House, forms a heritage zone that essentially freezes time. The preservation of the baldosas (clay floor tiles) and the original pulpit speaks to a community that understands the value of their inheritance. It serves as a reminder that heritage conservation isn’t just about government decrees; it’s about the town’s refusal to let their identity crumble.

To visit the Church of San Agustin in Bacong is to read a biography of the Visayan soul written in stone and brick. It is a narrative of technological adaptation by the friars, the terrified vigilance of a coastal town, the artistic triumph of Spanish organ builders, and the revolutionary fire of a local son. whether you are an architecture buff marveling at the unique brick facade or a history enthusiast tracing the steps of Leon Kilat, Bacong offers a profound connection to the past. It remains a spiritual lighthouse in Southern Negros, proving that some treasures don’t just belong in museums—they are living, breathing spaces that continue to watch over the changing tides of history.

|UnknownCebu|

Sources:

National Museum of the Philippines. “Parish Church of San Agustin, Bacong, Negros Oriental.” National Museum of the Philippines. February 10, 2022. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/02/10/parish-church-of-san-agustin-bacong-negros-oriental/.

National Museum of the Philippines. “News Archive: 2022 – Page 29.” National Museum of the Philippines. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/page/29/.

National Commission for Culture and the Arts. “Talapamana Visayas.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://talapamana.ncca.gov.ph/index.php/component/content/article/talapamana-visayas?catid=10&Itemid=101.

De Guzman, Roy John, and Juan Carlos Cham. “Letanía: Architectural documentation of the retablos of San Agustin Church in Manila.” Journal of Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism 1 (2020): 358–369. https://www.traditionalarchitecturejournal.com/index.php/home/article/view/358.

Romanillos, Emmanuel Luis A. “Augustinian Recollect Legacy to the Church in Negros Island.” Semantic Scholar. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f448/3636f76725867f3e0cb5976fdb02e45ac64c.pdf.

Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. “Bacong, Negros Oriental: Exemplary Heritage Town.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, April 3, 2017. https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/258982/bacong-negros-oriental-exemplary-heritage-town/.

Partlow, Judy F. “Bishop Reassigns Members of Diocese of Dumaguete.” Visayan Daily Star, April 16, 2014. https://archives.visayandailystar.com/2014/April/16/negor1.htm.

Organographia Philipiniana. “Bacong.” Organographia Philipiniana. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.orgph.com/organs/bacong.

Wikipedia. “Bacong Church.” Last modified October 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bacong_Church.

Wikipedia. “Bacong.” Last modified October 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bacong.

Wikipedia. “Leandro Arrué Agudo.” Last modified October 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leandro_Arr%C3%BAe_Agudo.

Villareal, Melo. “Visiting the San Agustin Church in Bacong, Negros Oriental.” Out of Town Blog, August 7, 2014. https://outoftownblog.com/visiting-the-san-agustin-church-in-bacong-negros-oriental/.

PH Tour Guide. “Parish Church of Saint Augustine of Hippo.” PH Tour Guide. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.phtourguide.com/parish-church-of-saint-augustine-of-hippo/#google_vignette.

Carcar Families. “Leon Kilat: And Then All Went Quiet on the Carcar Front (Part III, Epilogue).” Carcar Families (blog), April 9, 2014. https://carcarfamilies.wordpress.com/2014/04/09/leon-kilat-and-then-all-went-quiet-on-the-carcar-front-part-iii-epilogue/.

Poliquit, AJ. “Lightning Visit to Bacong.” The Transcendental Tourist (blog), September 5, 2013. https://ajpoliquit.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/lightning-visit-to-bacong/.

Negros Oriental. “Towns and Cities.” Negros Oriental (Weebly). Accessed November 27, 2025. https://negrosoriental.weebly.com/towns-and-cities.html.

Scribd. “Bacong NEGROS ORIENTALHISTORY.” Scribd. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/499391475/Bacong-NEGROS-ORIENTALHISTORY.