The Rocha Ancestral House, nestled in the historic Sitio Ubos of Tagbilaran City, Bohol, isn’t just a house—it’s a time capsule forged from coral stone, molave, and the immense wealth of 19th-century maritime trade. Often referred to simply as Casa Rocha, this architectural behemoth is one of the Visayas’ most authentic and complete examples of the Bahay na Bato typology. Built in 1831 (as indicated by a relief on a doorway) by the immensely successful merchant, Julian Rocha, its location in Sitio Ubos—which was, at the time, Tagbilaran’s exclusive and thriving port—is no accident. The ground floor was originally designed as a sturdy, ventilated bodega (warehouse) for merchandise, literally placing the family’s opulent life directly above the commercial engine that fueled it. The very existence of this structure, with its sophisticated joinery and robust materials, served as an unmistakable declaration of the Rocha family’s apex status among the Boholano mercantile elite.

The complex’s history is fascinatingly dual, involving two adjacent structures that tell a parallel story of heritage and conservation challenges. The house most famously known for its earlier public life is the Casa Rocha-Suarez. This particular structure underwent a comprehensive and celebrated professional restoration in 2005, meticulously executed by architect German Torrero. For a time, it functioned as a pristine museum, showcasing an extraordinary collection of 18th- and 19th-century family heirlooms and furniture, offering the public a rare glimpse into the lavish lifestyle of a prosperous trading dynasty. However, the photograph you provided—showing palpable signs of deterioration, graying wood, and significant overgrowth—is likely a stark visual record of this very house after it regrettably ceased museum operations and closed its doors to the public around 2015. It brutally illustrates a core truth of heritage preservation in the tropics: that a period of “excellent condition” achieved by restoration can quickly revert to decay without perpetual, active maintenance.

Meanwhile, the narrative of the other, adjacent property—the original Casa Rocha (sometimes known as the Antonio Rocha House)—took a different and more permanent turn toward preservation. Associated with an inscription dating it to 1831, suggesting it might be the oldest surviving residential structure in Bohol, this house received the highest form of state protection in 2020. It was officially acquired by the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) and designated a National Cultural Treasure (NCT). The NMP’s subsequent intervention, involving a large-scale, state-managed repair and conservation project, signifies an institutional, long-term commitment to its survival. This acquisition is a critical win for Philippine heritage, securing the future of a structure that memorializes the generational transition of the Rocha family from 19th-century commercial dominance to 20th-century political power, notably with Fernando G. Rocha serving as Bohol’s first elected governor from 1910 to 1916.

Architecturally, the Rocha Ancestral House stands as a masterpiece of adaptive synthesis, merging indigenous design with Spanish formality and likely Chinese craft influences. It adheres strictly to the Bahay na Bato standard, designed for both climate resilience and earthquake protection. Its material palette is pure elite coastal Bohol: the lower level is built on robust coral stone foundations, which elevate the structure and allow for essential ventilation, while the upper floor, housing the family’s sala (living room) and quarters, is constructed from durable, sophisticatedly joined hardwoods. Inside, it boasts features marking its status, such as an original tray ceiling and an English chandelier—a testament to its connections to global trade. Perhaps its most structurally and decoratively unique element is found on the main double door: the doorjambs feature pegs meticulously carved into rosettes, a detail noted by scholars as “unique in the archipelago.”

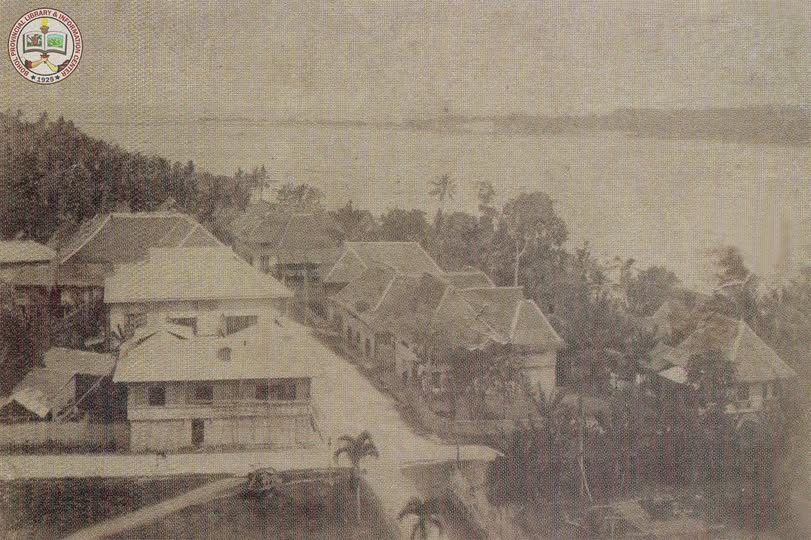

The physical location itself, Sitio Ubos, is central to the house’s significance. Literally meaning “lower portion,” it was the economic heart of Tagbilaran until shifting trade routes and the construction of a causeway to Panglao Island led to its commercial decline. However, this very stagnation had an unexpected silver lining for history. As the area lost its mercantile glory, its valuable houses were spared from demolition or modern, historically inaccurate renovations. They were simply left to stand, resulting in the preservation of an entire ensemble of 19th-century architecture, including the Hontanosas, Beldia, and Yap Houses. This collective heritage was formally recognized in 2002 when Sitio Ubos was officially declared a “Cultural Heritage Area.”

Ultimately, the Rocha Ancestral House, particularly the NMP-acquired National Cultural Treasure, is indispensable. It is a powerful, tangible link to the founding of Bohol’s wealthy elite, a singular record of high-craft colonial architecture, and a living example of a dynastic seat that has endured for nearly two centuries. The visual evidence of decay contrasted with the massive state restoration effort offers a profound case study in heritage stewardship—a crucial reminder that preserving these complex, vulnerable monuments requires not just initial vision, but perpetual institutional commitment. It stands now as the anchor for the revitalization of the entire Sitio Ubos district, ensuring its irreplaceable account of Boholano life and power is secured for future generations.

Sources:

Akpedonu, Erik. “Sitio Ubos: What remains when heritage conservation fails.” BluPrint, January 18, 2018. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://bluprint-onemega.com/architecture/heritage/sitio-ubos-heritage-conservation/.

Akpedonu, Erik, and Czarina Saloma-Akpedonu. Casa Boholana: Vintage Houses of Bohol. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2011.

Bohol Vintage Houses. “Posts.” Accessed November 19, 2025. https://boholvintagehouses.wordpress.com/posts/.

Bohol.ph. “Casa Rocha-Suarez Heritage Center.” Accessed November 19, 2025. http://www.bohol.ph/resort.php?businessid=103.

City Government of Tagbilaran. “History.” Accessed November 19, 2025. https://tagbilaran.gov.ph/history/.

Guide to the Philippines. “Casa Rocha-Suarez Heritage Center.” Accessed November 19, 2025. https://guidetothephilippines.ph/destinations-and-attractions/casa-rocha-suarez-heritage-center.

Larkin, John A. Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Perreras, Ericca Louise J., Alyssa Camille S. Castro, and Nicole P. Zabala. “BAHAY NA BATO (Central Visayas) (TD Bahay Na Bato Final PDF).” Group research assignment, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, 2020. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/presentation/447429202/BAHAY-NA-BATO-FINAL.

Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. “Tagbilaran, Bohol identifies 30 heritage structures.” Lifestyle.INQ, December 24, 2018. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/318855/tagbilaran-bohol-identifies-30-heritage-structures/.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Bahay na bato,” last modified date unknown. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahay_na_bato.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Governor of Bohol,” last modified date unknown. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Governor_of_Bohol.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Mayor of Tagbilaran,” last modified date unknown. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayor_of_Tagbilaran.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Tagbilaran,” last modified date unknown. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tagbilaran.