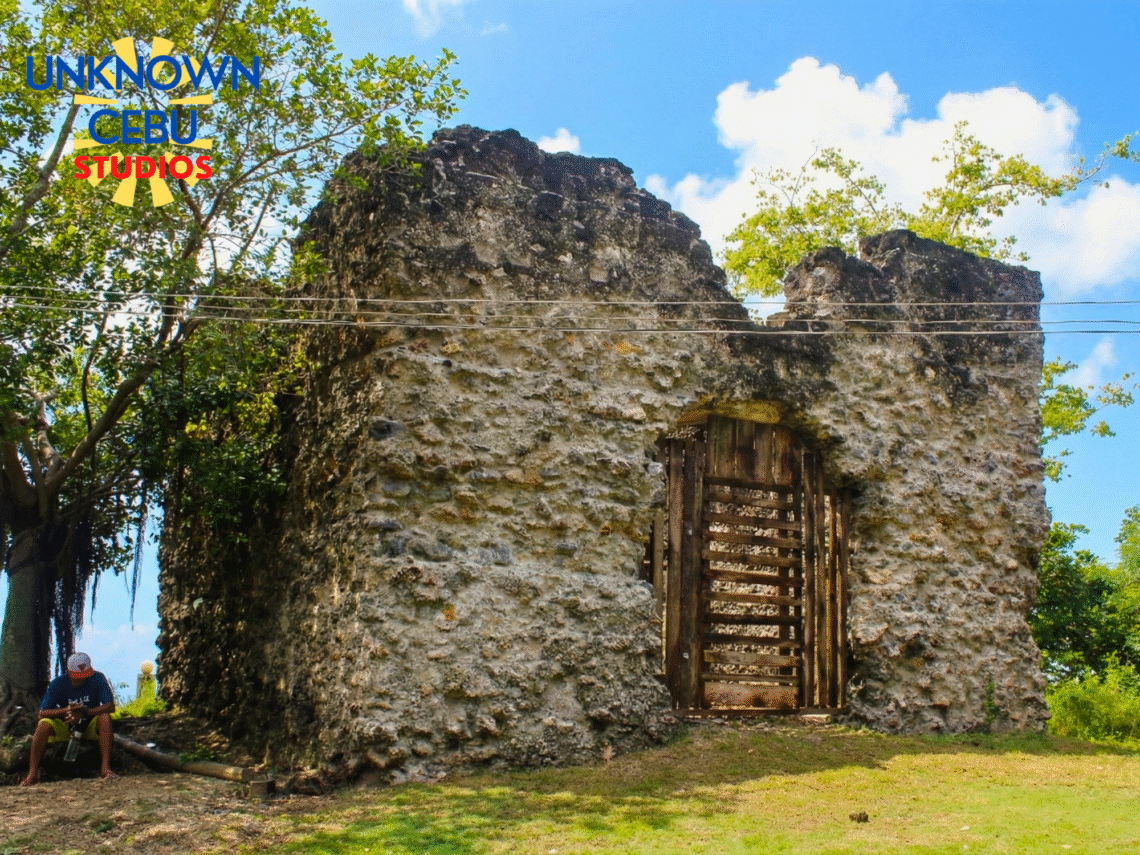

Part of UnknownCebu’s Dalaguete trek is one which we have made before: the Baluarte at Obong. Once, there was fear in the south of Cebu due to pirate raids, that fear is embodied in the ruins of the Obong Watchtower, a structure that sits stoically beside the famous cold spring. While tourists flock here to wash off the heat of the road in the brackish waters of the local spring, few realize they are swimming in the shadow of a kill zone. This was not built for aesthetics; it was built to stop the “season of fear,” the winds that brought the warships of the slave raiders from the south. The Obong tower wasn’t just a building; it was a desperate refusal to vanish.

To understand the architecture of this ruin, you have to look past the moss and the missing roof. This is a classic example of the “Baluarte” system orchestrated by the legendary warrior-priest, Fr. Julian Bermejo, the “El Padre Capitan” of Boljoon. While the town center had its own defenses (the Kiosko built in 1768), Obong was the strategic back door. Constructed from rough-hewn coral stone, likely quarried through the grueling polo y servicio labor system under direction of the priests, (though it could also be entirely possible that the natives were motivated by their own need to defend themselves) the walls were bound together by argamasa, a lime mortar that local oral history insists was strengthened with egg whites. It functioned as part of a massive, analogue “internet of stone” that stretched from Santander to Carcar. When a sentinel at Obong spotted a sail on the horizon, he didn’t just panic; he lit a signal fire or blew a budyong (conch shell), triggering a chain reaction that would ring the church bells in the Poblacion, miles away.

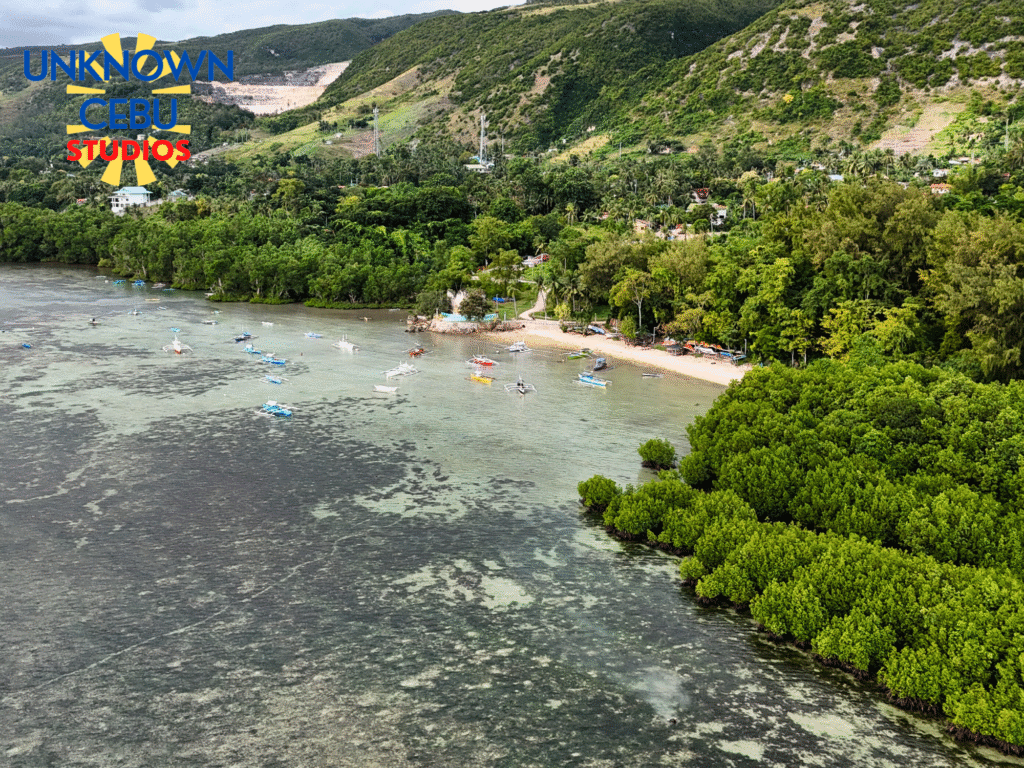

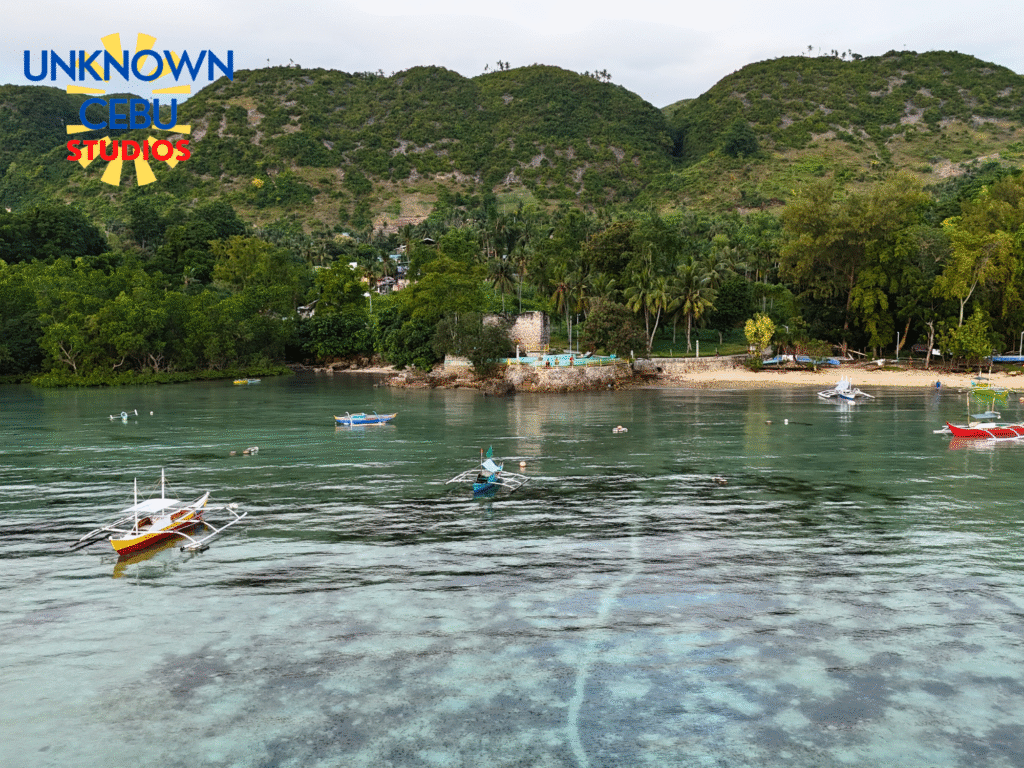

But why here? Why fortify this specific patch of shoreline? The answer lies in the water itself. In naval warfare, fresh water is the ultimate logistical constraint. The raiders, operating far from their home ports in Sulu or Maguindanao, needed to replenish their casks. The Obong Spring, with its massive discharge of fresh water meeting the sea, was a prime refueling station. By placing a cannon-armed watchtower right next to the source, the Dalaguetnons were engaging in “resource denial.” If the raiders wanted water, they had to bleed for it. It turns the picturesque swimming hole into a historic battleground, where the friction between the indigenous militia and the maritime invaders was decided by who controlled the tap. Aside from being near the water, it had a strategic position at the center of a local hotspot which had been inhabited since pre-Spanish times due to the well, and the slightly elevated outcrop the watchtower was built upon.

The site is also the intersection of history and myth, anchored by the massive Dalakit (Balete) tree that looms near the ruins. It is impossible to separate the stone tower from this living giant. According to local lore, this is the very spot where the town earned its name. As the story goes, Spanish soldiers arrived here and asked a local woman for the name of the place. Confused, she thought they were asking about the tree and answered “Dalakit,” which the Spaniards corrupted into “Dalaguete.” It is a poetic irony that the town’s identity is rooted in a tree that predates the Spanish conquest, yet it is guarded by a Spanish-era fortification. The tree, often feared as a dwelling for dili ingon nato (spirits), and the tower, a defense against human pirates, stand as dual guardians—one spiritual, one military. Though, it should be noted that this is but a story.

Today, the watchtower has undergone the strange alchemy of modern tourism. The National Museum of the Philippines recently declared the San Guillermo de Aquitania Church Complex a National Cultural Treasure, and while the glory largely goes to the poblacion, the Obong ruin, however, probably does not have the same declaration due to distance. However, there is a dissonance in seeing karaoke machines and snack stalls operating where sentinels once prayed to survive the night. The “Suroy Suroy Sugbo” initiatives have successfully monetized the heritage, turning the Baluarte into a backdrop for selfies. While this economic vitality ensures the ruin won’t be bulldozed, it risks sanitizing the violence that necessitated its construction. The risk still exists, if a bit lessened. A worthy opportunity to preserve the baluarte exists also because of its proximity to the spring.

Ultimately, the Obong Watchtower is a testament to the grit of the vernacular coast. It represents the transition of Dalaguete from a settlement that fled to the mountains at the first sign of a sail, to a community that stood its ground. It is a monument to the nameless laborers who hauled coral blocks from the reef and the militias who stood watch under the punishing sun. When you visit, look closely at the embrasures—the narrow slits in the walls. They frame the same horizon we look at today, but the view is different. We see a beautiful strait; they saw the edge of survival long ago.

Sources:

Gerra, Jocelyn, and Ruel Rigor. Cebu Heritage Frontier: Argao, Dalaguete, Boljoon, and Oslob. Cebu City: Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc., 2003.

Parish of San Guillermo de Aquitania. 300 Years of Grace and Pride: Dalaguete 300-Year Souvenir Program. Dalaguete, Cebu: Parish of San Guillermo de Aquitania, 2011.

“Fray Julian Bermejo, OSA: El Padre Capitan Boljoon.” Chronicles of the Basilica del Santo Niño de Cebu. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://santoninodecebubasilica.org/chronicles/fray-julian-bermejo-osa-el-padre-capitan-boljoon/.

GMA Regional TV. “Church in Dalaguete, Cebu Named National Cultural Treasure.” GMA News Online, October 14, 2022. https://www.gmanetwork.com/regionaltv/features/100458/church-in-dalaguete-cebu-named-national-cultural-treasure/story/.

“History.” Best of Dalaguete. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://bestofdalaguete.weebly.com/history.html.

“Obong Spring.” Best of Dalaguete. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://bestofdalaguete.weebly.com/obong-spring.html.

“Tourist Attractions.” Best of Dalaguete. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://bestofdalaguete.weebly.com/tourist-attractions.html.

“HISTORY 2-1.” Scribd. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/688438096/HISTORY-2-1.

Mike. “Dalaguete Peak (Osmeña Peak).” Mike’s Eventures (blog), July 7, 2018. https://mikeeventures.wordpress.com/2018/07/07/dalaguete-peak/.

Mamites, Kyle. “Kyle’s Mamites.” WordPress (blog). Accessed December 17, 2025. https://kylesmamites.wordpress.com/.

Mulit, Shane. “Shane Mulit.” WordPress (blog). Accessed December 17, 2025. https://shanemulit15.wordpress.com/.