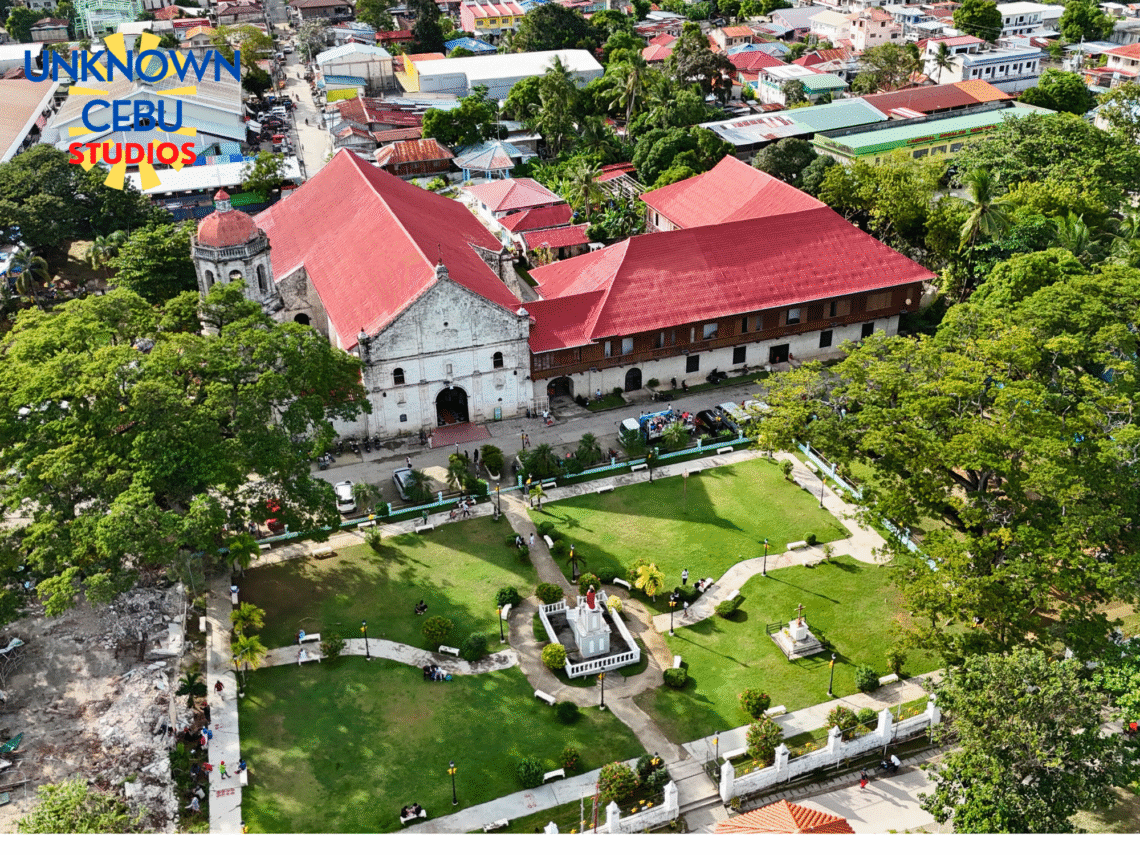

There is a distinct shift in the air when you travel down the southeastern flank of Cebu, past the bustling city and into the quieter, salt-sprayed towns facing the Bohol Sea. We often think of Dalaguete solely as the “Vegetable Basket of Cebu,” a place of high peaks and cool mountain breezes, but down in the poblacion, a different kind of majesty dominates the landscape. Standing as a massive coral stone sentinel against the blue horizon is the San Guillermo de Aquitania Parish Church, a structure that feels less like a mere building and more like a geomorphic feature of the coastline itself. Recently declared a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines, this church is a survivor, a “Fortress of Faith” that narrates a story spanning three centuries. It is a testament to the era when the church was not just a sanctuary for the soul, but a physical citadel against the terrifying reality of Moro slave raiders that once plagued these waters in front of the Dalaguete church.

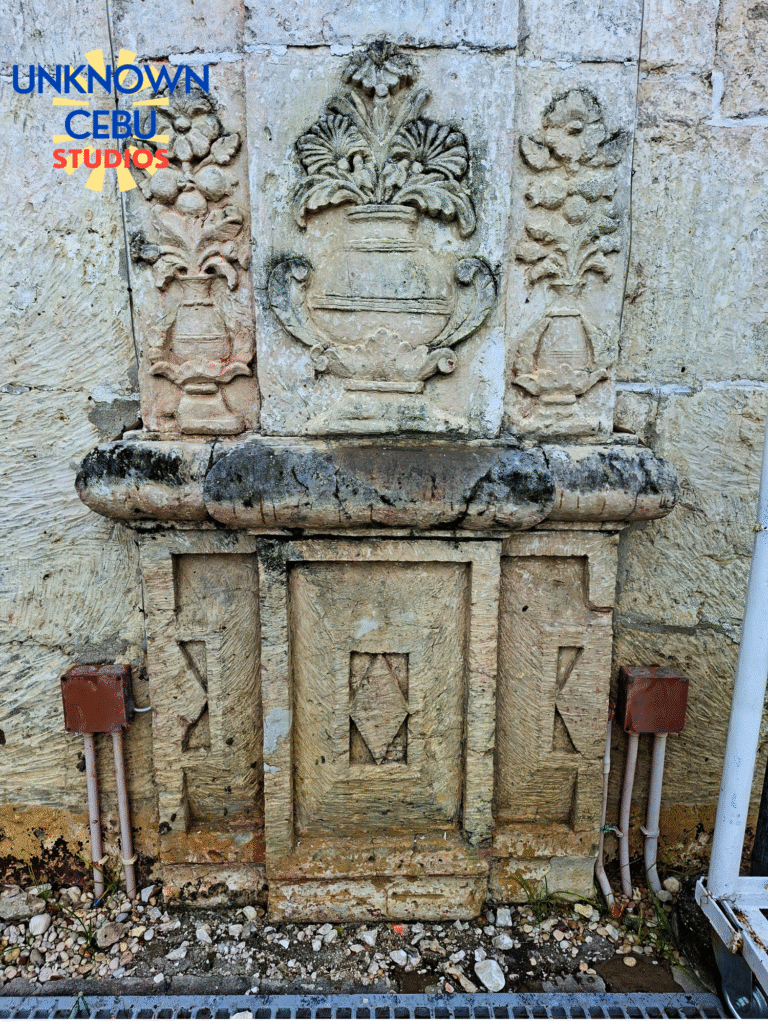

To understand the architecture of San Guillermo, you have to understand the fear that dictated its design. This is classic “Earthquake Baroque” at its most robust, yet it carries the scars of a militarized past. The facade is a study in vertical dominance, divided by heavy cornices and flanked by massive pilasters that look deceptive—they aren’t just decorative; they are the skeletal strength holding the structure against the trembling earth. The church complex was designed as a line of defense, part of the great coastal grid orchestrated by the legendary “Padre Kapitan” Julian Bermejo. If you stand in the plaza and look at the octagonal belfry, you’ll notice it stands apart from the main nave. This wasn’t a mistake; it was a calculated engineering decision. In the event of a catastrophic earthquake, the falling tower would not crush the congregation inside the church. Furthermore, this belfry served a dual purpose: it was the town’s bantayan (watchtower), where the ringing of the bells signaled not just the Angelus, but the approach of paraws from the south.

Stepping through the heavy wooden doors, the defensive, rugged exterior gives way to a surprisingly delicate and vibrant interior. This is where the heritage of Dalaguete truly sings. Inside are five retablos done mostly in the roccoco style which were installed at the time of construction. While the stone shell was laid in the early 1800s by Fray Juan Chacel using the polo y servicio labor system—hewing coral stones from the local reefs—the artistic soul of the church ceiling belongs to the 1930s. The ceiling is a breathtaking canvas of trompe l’oeil paintings executed by the master Canuto Avila. Unlike the somber, didactic art of the earlier Spanish period, Avila’s work is a celebration of “baby blues, pinks, and greens,” a decorative explosion that tricks the eye into seeing three-dimensional coffers and moldings on flat sheets. It is a “fragmented catechism,” where the narrative isn’t just about fear of the divine, but about the beauty of the heavens. It is a rare example of pre-war Cebuano artistry that has survived to this day, offering a stark, beautiful contrast to the limestone greys of the walls.

The Ceiling plan by Project Kisame

The church’s location is no accident, rooted deeply in the indigenous history of the town. Long before the Spaniards laid the first stone in 1802, this area was known as “Obong” or “Dalakit,” named after the massive dalakit (balete) trees that served as spiritual anchors and trading posts for the pre-colonial Cebuanos. The Spanish Reducción policy effectively superimposed the Catholic faith over this ancient spiritual geography, replacing the sacred tree with the stone altar. Yet, the name remains, a linguistic ghost of the animist past. Just across from the belfry stands the convent, completed in 1832. It is a stunning example of the bahay na bato style, with a solid stone ground floor and a graceful wooden upper story. It served as the administrative heart of the town in so far as the church was concerned, surviving fires and wars that claimed so many other rectories across the archipelago. Inside the convent is the parish museum which contains many antiques from the church.

One of the most fascinating quirks of this heritage site is the lingering mystery of its patron saint. The church is officially dedicated to San Guillermo de Aquitania, the warrior-duke and cousin of Charlemagne, which fits perfectly with the church’s history as a fortress against raiders. However, the town celebrates its fiesta in February, the feast day of San Guillermo de Maleval, the hermit. It’s a delightful historical conflation—the “Warrior” versus the “Hermit”—likely born from centuries of confusion and the evolving needs of the parish. Whether the town prayed to the soldier for protection or the hermit for penitence, the devotion has remained constant. This duality is carved into the very identity of the parish, adding a layer of rich cultural texture that you won’t find in history books alone.

Today, San Guillermo de Aquitania stands as one of the few heritage structures that shrugged off the devastating 7.2 magnitude earthquake of 2013 with barely a scratch, while newer structures crumbled. Its recent elevation to National Cultural Treasure status is a long-overdue recognition of its engineering brilliance and artistic value. But beyond the plaques and the titles, the church remains a living space. It is a place where the salt air eats at the coral stone, requiring constant care, and where the faithful still gather under Avila’s painted heavens. It is a reminder that in Cebu, our history is not kept in museums; it is built into the walls we pass by every day.

Sources (Keep looking bros, maybe you’ll find it.)

Alix, Louella Eslao, Estan L. Cabigas, Antonio P. Diluvio, and Jose Eleazar R. Bersales, eds. Balaanong Bahandi: Sacred Treasures of the Archdiocese of Cebu. Cebu City: Cathedral Museum of Cebu, Inc. and University of San Carlos Press, 2010.

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R., and Ino Manalo, eds. Integración/Internación: The Urbanization of Cebu in Archival Records of the Spanish Colonial Period. Cebu City: University of San Carlos Press and National Archives of the Philippines, 2017.

Casinillo, Leo. “San Guillermo de Aquitania May Not Be Dalaguete’s Patron Saint!!!” Sa Akong Ka-laagan (blog), February 4, 2012. http://leocasinillo.blogspot.com/2012/02/san-guillermo-de-aquitania-may-not-be.html.

Chalacuna. “El Gran Baluarte: A Testament to Father Bermejo’s Legacy in Boljoon, Cebu.” Waivio. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.waivio.com/@chalacuna/el-gran-baluarte-a-testament.

History of Sulu. “Moro Raids.” July 17, 2014. https://historyofsulu.wordpress.com/2014/07/17/moro-raids/.

Magsumbol, Caecent No-ot. “Dalaguete Church Declared as National Cultural Treasure.” The Freeman (Philstar.com), February 13, 2024. https://www.philstar.com/the-freeman/cebu-news/2024/02/13/2333012/dalaguete-church-declared-national-cultural-treasure.

Mikeeventures. “Dalaguete Peak.” Mikeeventures (blog), July 7, 2018. https://mikeeventures.wordpress.com/2018/07/07/dalaguete-peak/.

MyCebu. “After Boljoon, Dalaguete Seeks Return of Stolen Church Items.” MyCebu.ph. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/dalaguete-stolen-images/.

———. “Fr. Julian Bermejo: ‘El Padre Capitan’ of Oslob and Boljoon.” MyCebu.ph. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/fr-julian-bermejo-oslob/.

National Historical Commission of the Philippines. “Simbahan ng San Guillermo de Aquitania.” National Registry of Historic Sites and Structures in the Philippines. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://philhistoricsites.nhcp.gov.ph/registry_database/simbahan-ng-san-guillermo-de-aquitania-dalaguete-church/.

Peterson, John A. “World Powers at Play in the Western Pacific: The Coastal Fortifications of Southern Cebu, Philippines.” In The Archaeology of Interdependence, edited by D.B. Bamforth and A.J. Clark, 61–79. New York: Springer, 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302207630_World_Powers_at_Play_in_the_Western_Pacific_The_Coastal_Fortifications_of_Southern_Cebu_Philippines.

Reddit. “What Incentivized Moro Raids on the Visayas?” r/FilipinoHistory, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/FilipinoHistory/comments/1k17x7q/what_incentivized_moro_raids_on_the_visayas/.

Traveler on Foot. “Dalaguete.” Traveler on Foot (blog), January 22, 2010. https://traveleronfoot.wordpress.com/2010/01/22/dalaguete/.

Wikipedia. “Spanish–Moro Conflict.” Last modified December 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish%E2%80%93Moro_conflict.