When you stand on the seawall of Dalaguete today, looking out over the calm, azure waters of the Bohol Sea, it is almost impossible to imagine that this horizon was once the source of absolute terror. We know Dalaguete now as the “Vegetable Basket of Cebu,” a peaceful town of misty peaks and cool highland breezes, but if you strip away the modern pavement and the bustling market sounds, you find the skeleton of a fortress town built for survival. The history of this coastline isn’t written in ink, but in the heavy coral stones of its watchtowers and the rusting iron of the lonely cannon facing the strait. For centuries, specifically during the height of the “Moro Wars” from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, living here meant living in fear of the Habagat wind that filled the sails of slave-raiding fleets coming from the south. The structures we pass by carelessly today, often mistaking them for simple gazebos or decorations, were actually the line in the sand between life and enslavement for our ancestors.

To understand why a town needed to turn its church into a citadel, we have to look at the sheer scale of the threat. These weren’t petty pirates looking for gold; these were organized, state-sanctioned armadas from the Sultanates of Mindanao and Sulu, seeking the most valuable commodity in Southeast Asia: human beings. For decades, the Spanish administration in Manila was too far away and too ill-equipped to protect the Visayas, leaving towns like Dalaguete to fend for themselves. This necessity birthed a brutal but brilliant defensive grid masterminded by the legendary “El Padre Capitan,” Fr. Julian Bermejo. He didn’t just build forts; he built a telegraphic system using visual signals, flags by day, smoke and fire by night; that connected watchtowers from Santander all the way to Carcar. Dalaguete was a critical nerve center in this chain, and its residents were not passive victims but active defenders, manning their own barangayan fleets to chase down the raiders in open water.

The most prominent, yet most misunderstood, remnant of this era is the structure standing proudly in the town plaza: the Poblacion Watchtower. If you visit today, you’ll hear locals call it the “Kiosko,” and with its second-level pavilion added during a 1970s “beautification” project, it looks like a place for Sunday picnics. But look at the base. That solid, weathered coral stone foundation dates back to 1768 decades before even Father Bermejo arrived proving that Dalaguete had been fighting this war for generations. It was originally a two-level fortification designed to hold artillery and gunpowder, serving as the eyes of the town. While its sister tower in Obong sits as a romantic ruin near the spring, the Poblacion tower was adapted and plastered over, hiding its scars. It is a classic case of heritage adaptation, where the grim reality of a defensive bunker is masked by the needs of a modern civic center, yet it remains one of the oldest standing structures in the province.

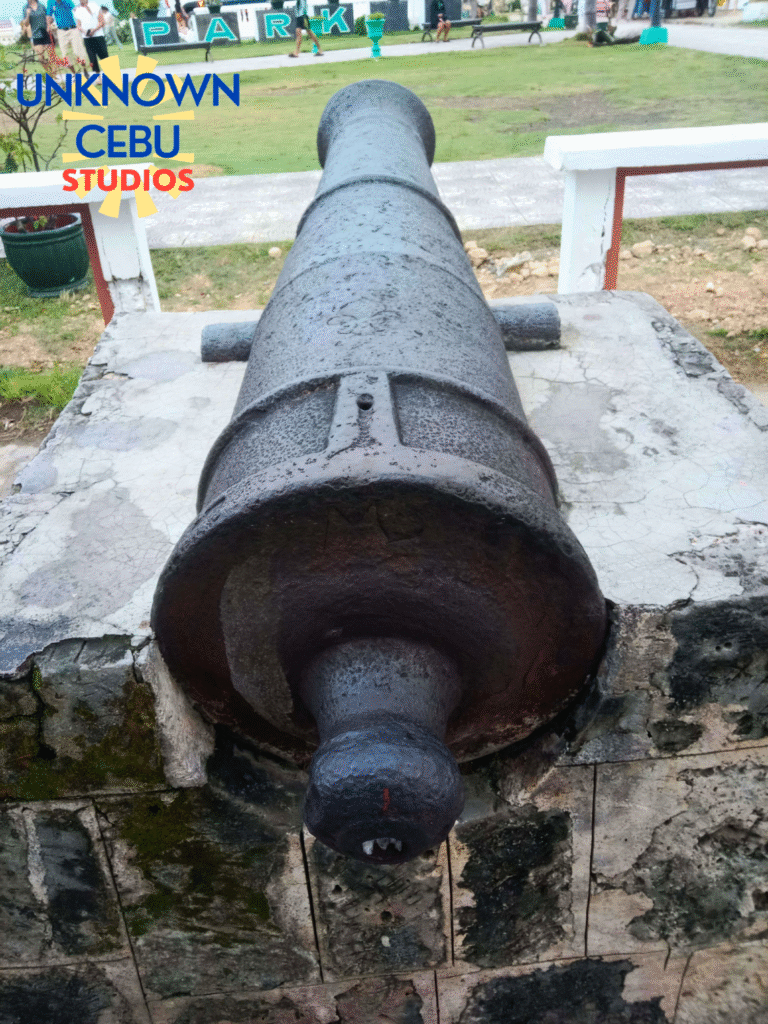

Resting silently nearby is perhaps the most tangible piece of this violent history: the iron cannon of Dalaguete. It’s easy to walk past it, dismissing it as a generic decoration, but a closer inspection of the rusting metal reveals a fascinating story. The markings on the breech, specifically the letter “M”, do not stand for a municipality, but likely for the Maestranza de Manila, the royal arsenal that cast the guns for the colony’s defense. Furthermore, the Roman numeral “XVII” stamped on the barrel isn’t a date or a serial number, but a weight marking indicating 17 hundredweight, which identifies it as a 6-pounder field gun. This was the perfect weapon for a coastal watchtower: heavy enough to shatter the hull of a wooden panco warship, but light enough to be maneuvered by the local militia. This cold piece of iron was once the loudest voice in Dalaguete, roaring in defiance against fleets that numbered in the dozenss.

The local lore surrounding this cannon is just as powerful as the gunpowder it once fired. Oral tradition in Dalaguete speaks of a time when the town was on the verge of annihilation, only for the raiders to retreat in terror after seeing a “giant” standing on the shore, holding the cannon and aiming it at them. This figure was identified as the town’s patron, San Guillermo. This legend perfectly illustrates how the people processed their trauma; they merged the identity of their patron saint with the reality of their defense. It also clears up the confusion about which San Guillermo the town honors. While the calendar may celebrate the Hermit, the legend of the “Warrior Saint” clearly points to William of Aquitaine, the soldier-duke. In the minds of the Dalaguetnons, their salvation was a partnership: the iron provided by the Spanish arsenal and the divine protection provided by their Warrior Saint.

Ultimately, the entire town center of Dalaguete is a monument to resilience. The San Guillermo de Aquitania Church, with its thick coral walls and fortified perimeter, was designed as a final refuge a “Church-Fortress” where the women and children fled when the warning bells rang. When we walk these streets today, we are walking on ground that was defended inch by inch. The National Museum has rightly declared the church complex a National Cultural Treasure, and the historical markers finally acknowledge the watchtower’s true purpose. But the real treasure isn’t just the architecture; it’s the realization that this community survived. The cannon points to the sea not in aggression, but in memory, standing guard over a peace that was bought with the blood, sweat, and unshakeable faith of the people of Dalaguete.

Sources:

Alix, Louella Eslao, Estan L. Cabigas, Antonio P. Diluvio, and Jose Eleazar R. Bersales, eds. Balaanong Bahandi: Sacred Treasures of the Archdiocese of Cebu. Cebu City: Cathedral Museum of Cebu, Inc. and University of San Carlos Press, 2010.

Bersales, Jose Eleazar R., and Ino Manalo, eds. Integración/Internación: The Urbanization of Cebu in Archival Records of the Spanish Colonial Period. Cebu City: University of San Carlos Press and National Archives of the Philippines, 2017.

Casinillo, Leo. “San Guillermo de Aquitania May Not Be Dalaguete’s Patron Saint!!!” Sa Akong Ka-laagan (blog), February 4, 2012. http://leocasinillo.blogspot.com/2012/02/san-guillermo-de-aquitania-may-not-be.html.

Chalacuna. “El Gran Baluarte: A Testament to Father Bermejo’s Legacy in Boljoon, Cebu.” Waivio. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.waivio.com/@chalacuna/el-gran-baluarte-a-testament.

History of Sulu. “Moro Raids.” July 17, 2014. https://historyofsulu.wordpress.com/2014/07/17/moro-raids/.

Magsumbol, Caecent No-ot. “Dalaguete Church Declared as National Cultural Treasure.” The Freeman (Philstar.com), February 13, 2024. https://www.philstar.com/the-freeman/cebu-news/2024/02/13/2333012/dalaguete-church-declared-national-cultural-treasure.

Mikeeventures. “Dalaguete Peak.” Mikeeventures (blog), July 7, 2018. https://mikeeventures.wordpress.com/2018/07/07/dalaguete-peak/.

MyCebu. “After Boljoon, Dalaguete Seeks Return of Stolen Church Items.” MyCebu.ph. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/dalaguete-stolen-images/.

———. “Fr. Julian Bermejo: ‘El Padre Capitan’ of Oslob and Boljoon.” MyCebu.ph. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/fr-julian-bermejo-oslob/.

National Historical Commission of the Philippines. “Simbahan ng San Guillermo de Aquitania.” National Registry of Historic Sites and Structures in the Philippines. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://philhistoricsites.nhcp.gov.ph/registry_database/simbahan-ng-san-guillermo-de-aquitania-dalaguete-church/.

Peterson, John A. “World Powers at Play in the Western Pacific: The Coastal Fortifications of Southern Cebu, Philippines.” In The Archaeology of Interdependence, edited by D.B. Bamforth and A.J. Clark, 61–79. New York: Springer, 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302207630_World_Powers_at_Play_in_the_Western_Pacific_The_Coastal_Fortifications_of_Southern_Cebu_Philippines.

Reddit. “What Incentivized Moro Raids on the Visayas?” r/FilipinoHistory, 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/FilipinoHistory/comments/1k17x7q/what_incentivized_moro_raids_on_the_visayas/.

Traveler on Foot. “Dalaguete.” Traveler on Foot (blog), January 22, 2010. https://traveleronfoot.wordpress.com/2010/01/22/dalaguete/.

Wikipedia. “Spanish–Moro Conflict.” Last modified December 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish%E2%80%93Moro_conflict.