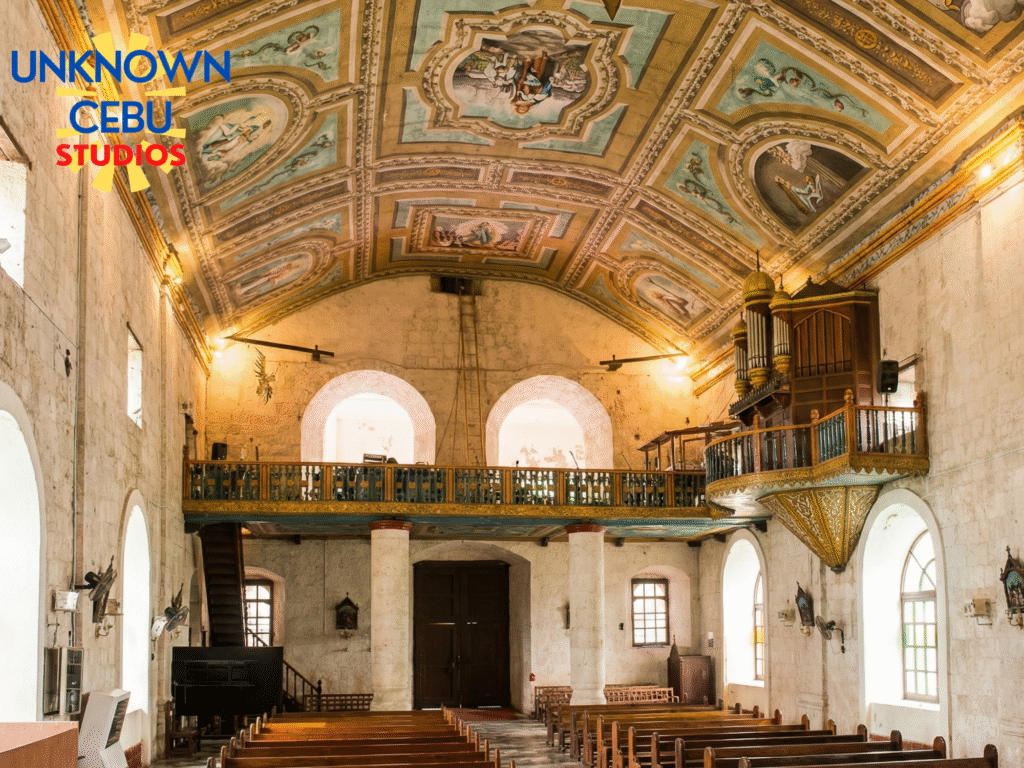

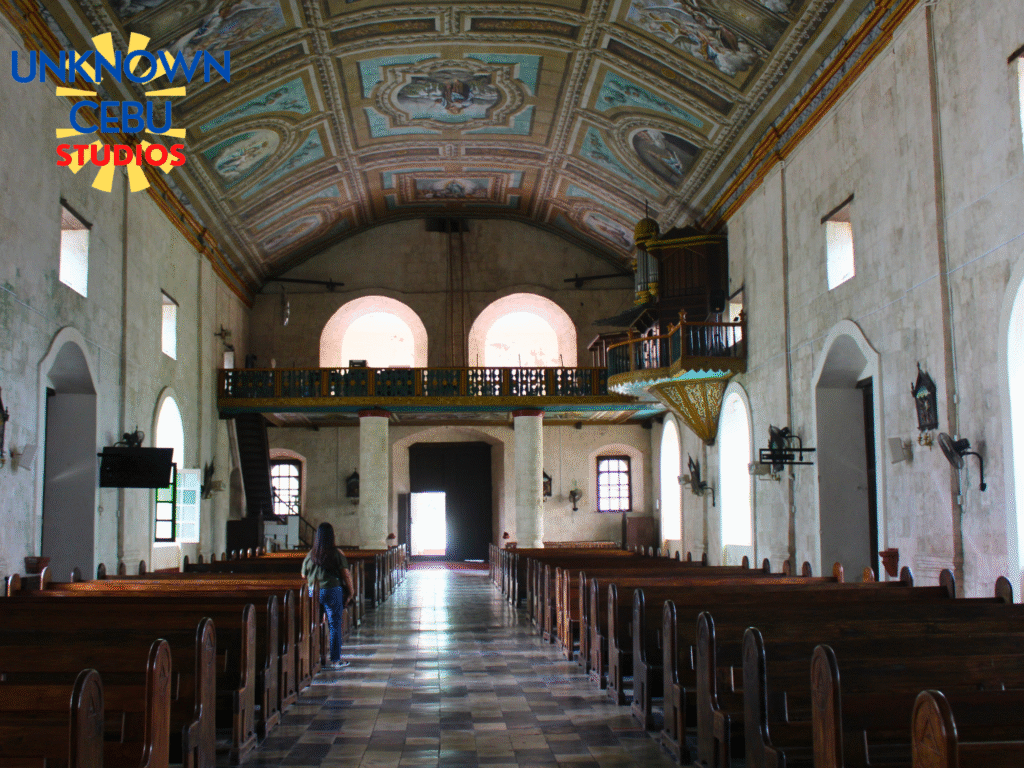

There is a specific quality to the air in Loay, where the mouth of the Loboc River spills into the Bohol Sea, a mix of brine and the ancient humidity of the river delta. It was here, upon a plateau chosen for defense against the slave-raiding fleets of the past, that the Holy Trinity Parish Church rose as a fortress of faith. But inside this coral stone edifice, beneath the painted ceilings of Raymundo Francia that attempt to pull heaven down to earth, sleeps a beast of wood and metal that has outlived empires. We often look at heritage structures and see only the shell, the stone walls and the retablos, forgetting that these buildings were designed to sing. The pipe organ of Loay, commissioned in 1841 when this town was a bustling transshipment hub of rice and beeswax, is not merely a piece of furniture. It is the lungs of the church, a mechanical marvel born from the surplus wealth of a riverine economy and the sheer audacity of 19th-century Boholanos who believed their prayers deserved to be carried on the wind of a thousand pipes.

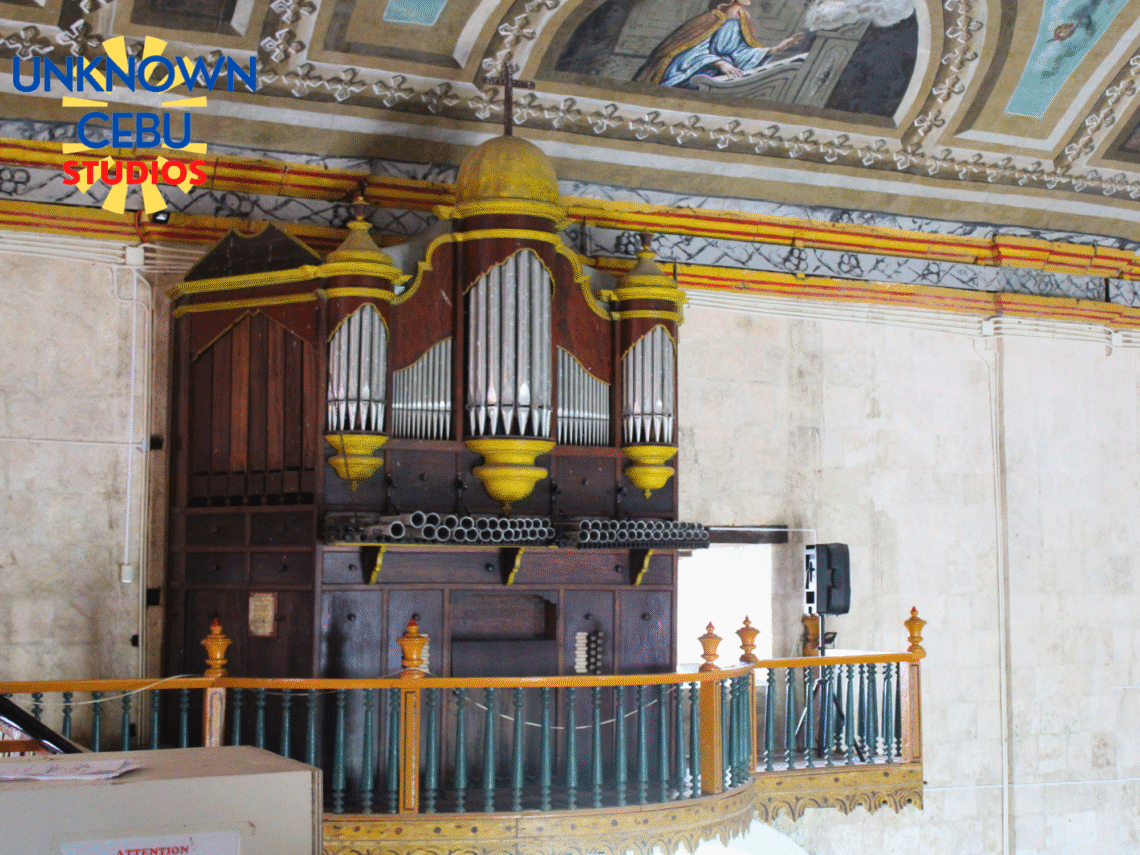

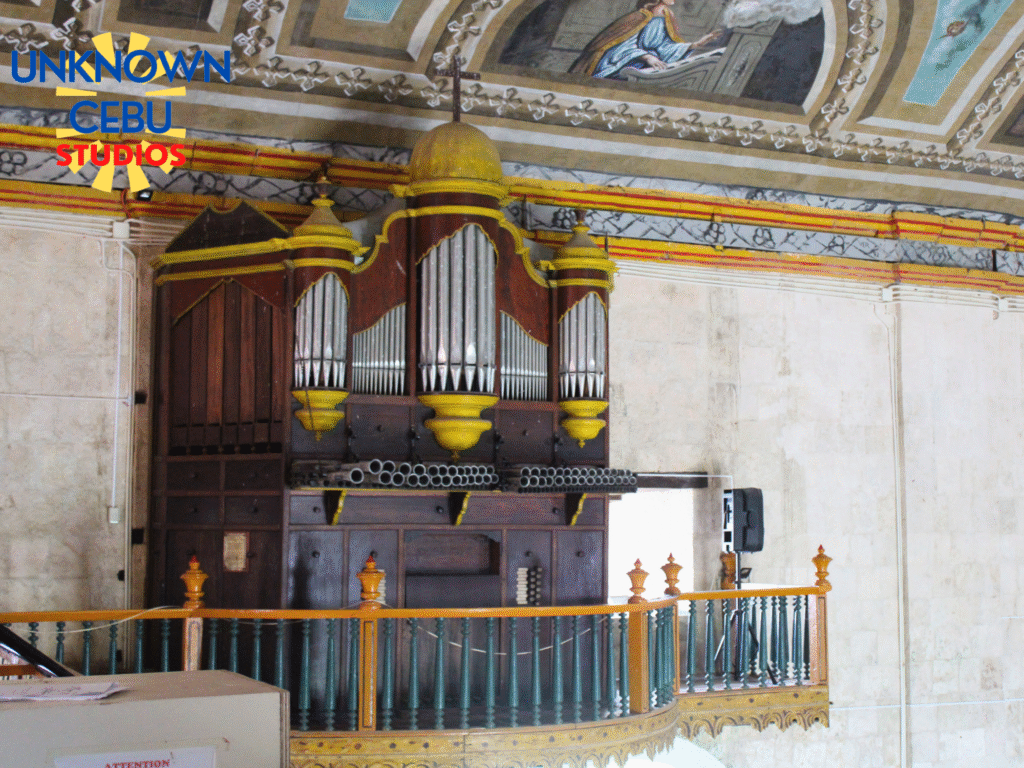

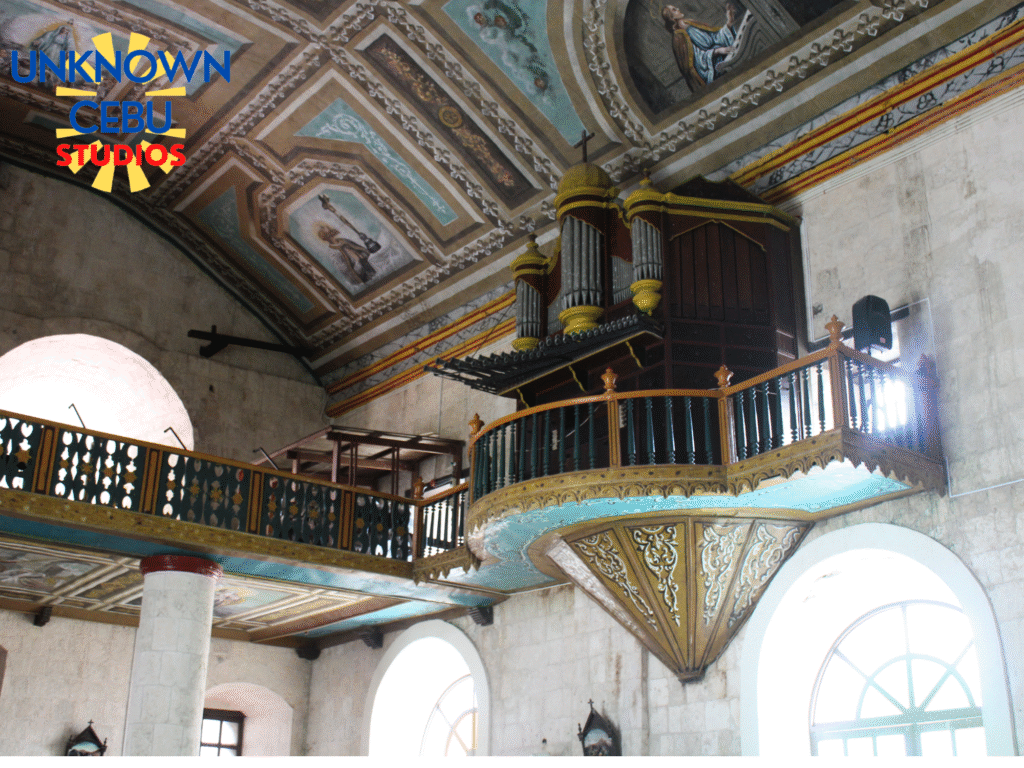

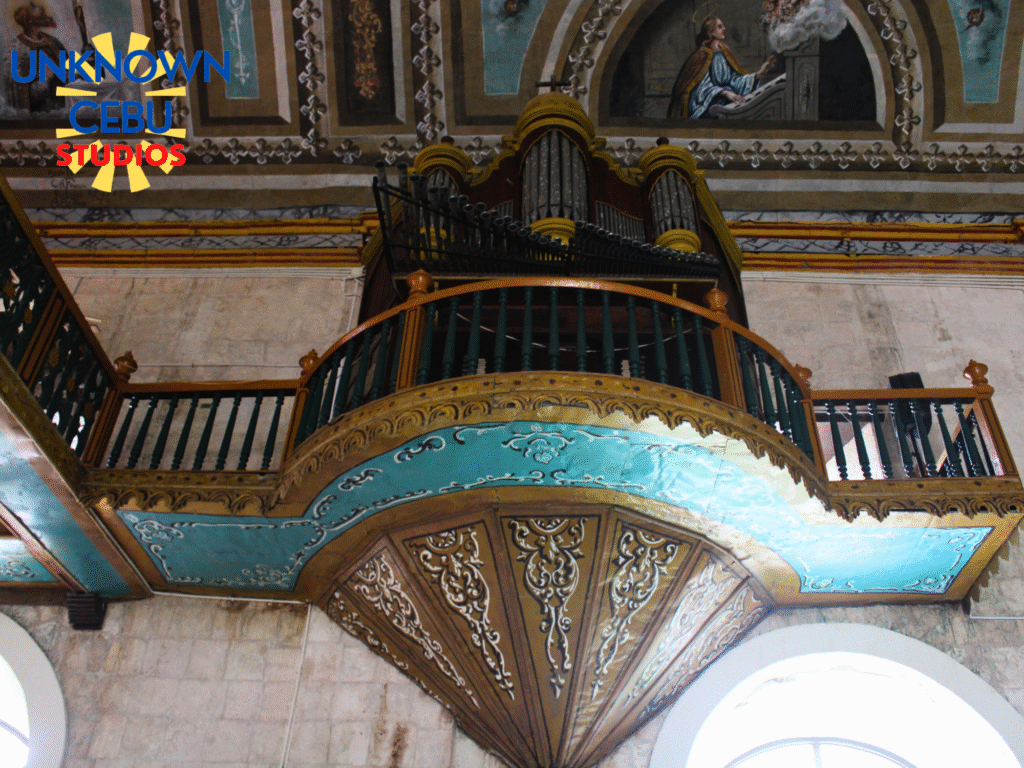

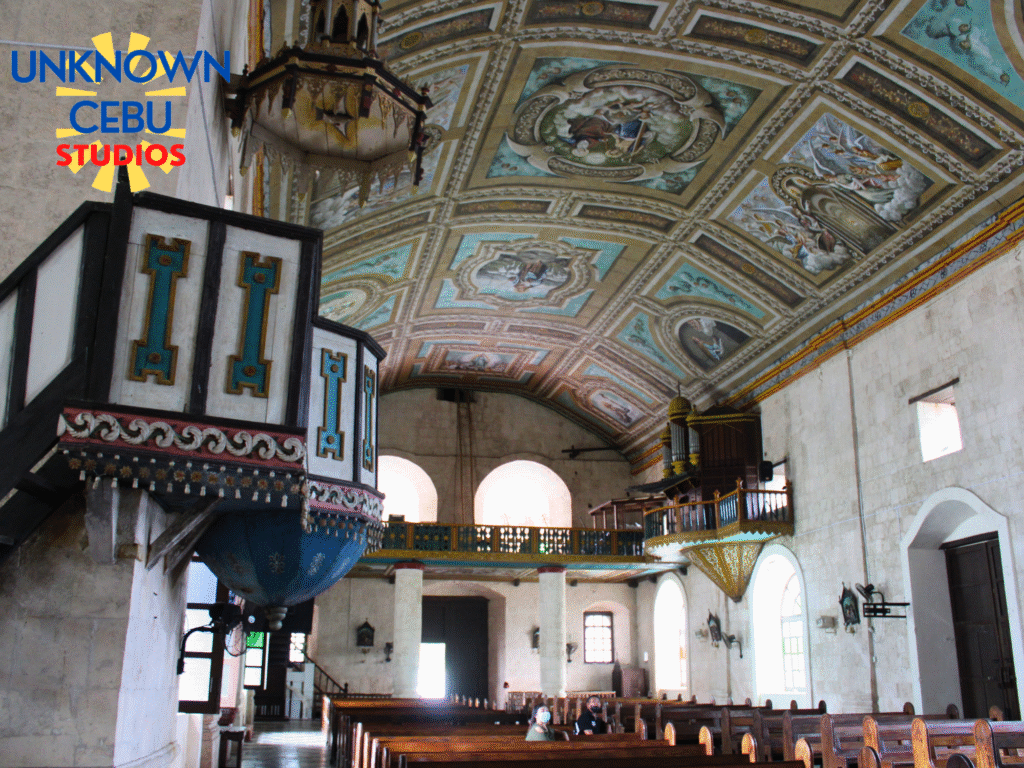

When you climb the creaking stairs to the choir loft, you are stepping into the workspace of the “Unknown Builders.” History has not preserved the names of the men who crafted this instrument nine years after the death of the legendary Fray Diego Cera, but their hands are everywhere. They were the carpenters who shaped the molave and narra, the tanners who cured the local leather for the bellows, and the smiths who cast the metal. This organ is the definitive proof of the “Bohol School”—a generation of local artisans who took the esoteric European technology of organ building and indigenized it. They created a “soundmark” distinct to the Visayas, an instrument that doesn’t just whisper but roars. Unlike the polite chamber organs of Europe, the Loay instrument possesses a Spanish Baroque temperament, designed to cut through the humidity and fill the cavernous acoustic of the stone nave with a brilliance that borders on the aggressive, a sonic mirror to the harsh, beautiful landscape outside.

The true secret of the Loay organ, however, lies in the floorboards: the pedals. While many provincial organs of that era were content with simple bass lines, the builders here installed a Bombarda 16’. This is a reed stop of immense gravity, a thunderous, brassy growl that rattles the ribcage. It was a statement of power, designed to support the full-throated singing of a congregation that, in 1841, would have sounded like a choir of angels and warriors combined. Coupled with the teclado partido—the divided keyboard that allows the organist to summon a solo trumpet in the right hand while playing a soft flute accompaniment in the left—and the whimsical “toy stops” of the Pajaritos (bird songs) and Tambor (drums), the instrument was a complete theatrical orchestra. It could mimic the sounds of nature during the Elevation or summon the dread of judgment day, all at the command of a single musician’s hands and feet.

Yet, like so much of our heritage, the Loay organ suffered through the dark years of neglect. Sometime after the Second World War, the music stopped. It wasn’t the war that silenced it, but the peace that followed. In a tragedy common to many Philippine heritage churches, the soft lead pipes became targets for theft, melted down to become fishing sinkers or solder. For decades, the organ stood as a hollowed-out carcass, a mute witness to the changing liturgy that replaced its majesty with the strumming of guitars. It became a ghost in the loft, its windchests empty, its keys frozen, dismissed as an obsolete relic of a colonial past. It took the vision of the late 1990s restoration movement and the skilled hands of the Diego Cera Organ Builders to reverse this decay, meticulously reconstructing the missing pipes and giving voice back to the silence to the Loay Pipe Organ.

The resilience of this instrument was tested most violently on October 15, 2013. When the earth shook Bohol to its core, the portico of the Holy Trinity Church—a later addition—peeled away and collapsed into rubble. But the original 1822 nave held its ground. High in the loft, amidst the dust and the terror of the aftershocks, the organ survived. While its sister instruments in Loon and Maribojoc were buried under mountains of debris, the Loay organ stood firm, a survivor of the “Great Tremor.” It spent years in a “freeze” phase, protected and dismantled while the church was painstakingly pieced back together, stone by anastylostic stone. Its survival is nothing short of miraculous, a testament to the structural integrity of the original church and perhaps, a bit of divine intervention for the Loay Pipe Organ.

Today, the Loay organ is more than just a musical instrument; it is a time machine. When the Bombarda sounds, it moves the same air, in the same acoustic volume, as it did 183 years ago. It connects us viscerally to the past in a way that no textbook can. It is a Living Heritage, a survivor of wars, revolutions, pilferage, and tectonic upheavals. As we stand in the restored church, listening to the ancient, reedy voice of the pipes interact with the trompe l’oeil heaven painted on the ceiling, we are reminded that heritage is not static. It is a fragile, breathing thing that requires our constant vigilance. The Loay organ is still singing, its voice a defiant, beautiful proof that the spirit of the Boholano people—and the craftsmanship of those unknown builders—cannot be easily silenced.

Sources:

Galinato, Judd C. “The Pastoral Ministry of Blessed León Inchausti and Blessed José Rada in Seven Parishes in Bohol 1885-1898.” Philippiniana Sacra (University of Santo Tomas). Accessed November 30, 2025. philsacra.ust.edu.ph/admin/downloadarticle?id=B810677FCB36E5292C3BCE3820982501.

AHA Centre. “Situation Update on the 15 October 2013 Bohol Earthquake.” PDF document in ASEAN Disaster Information Network Repository. Last modified November 30, 2013. adinet-repository.ahacentre.org/uploads/repository/document/file/369603f4-6b7e-4b83-98ee-ade2c966ded3.PDF.

“Gov’t to rebuild only 10 of 25 churches.” INQUIRER.net, October 20, 2014. newsinfo.inquirer.net/645460/govt-to-rebuild-only-10-of-25-churches.

Agustinos Recoletos. “6. Diego Cera (1762-1832).” Published June 12, 2024. agustinosrecoletos.org/2024/06/6-diego-cera-1762-1832/?lang=en.

Diego Cera Organbuilders, Inc. “Visayas.” Accessed November 30, 2025. diegocera.com/Diego_Cera_Organbuilders/Visayas.html.

Diego Cera Organbuilders, Inc. “The Organbuilders.” Accessed November 30, 2025. dcob.diegocera.com/the_organbuilders.htm.

“Loay.” ORGPH, The Philippine Pipe Organ Resource Center. Accessed November 30, 2025. orgph.com/organs/loay.

“Holy Trinity Church – Loay.” ORGPH, The Philippine Pipe Organ Resource Center. Accessed November 30, 2025. orgph.com/locations/holy-trinity-church-loay.

Tariman, Pablo A. “Cultural agencies come together for Bohol, Visayas.” INQUIRER.net, October 27, 2013. lifestyle.inquirer.net/174298/cultural-agencies-come-together-for-bohol-visayas/.

Tariman, Pablo A. “Landmark CD collection by Swiss organist highlights historic Philippine pipe organs.” INQUIRER.net, March 17, 2012. lifestyle.inquirer.net/27973/landmark-cd-collection-by-swiss-organist-highlights-historic-philippine-pipe-organs/.

“Baclayon’s pipe organ plays beautiful music…again.” Philstar.com, December 14, 2008. philstar.com/cebu-lifestyle/2008/12/14/423532/baclayons-pipe-organ-plays-beautiful-musicagain.

“Loay Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 21, 2024. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loay_Church.

“Bamboo Organ.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 30, 2025. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamboo_Organ.

u/Bohol_Narra. “Free Friday: Resurrection of a “dead” church (Our Lady of Light Parish, Loay, Bohol, Philippines).” Reddit, r/Catholicism, March 25, 2022. reddit.com/r/Catholicism/comments/tnjyxo/free_friday_resurrection_of_a_dead_church_our/.