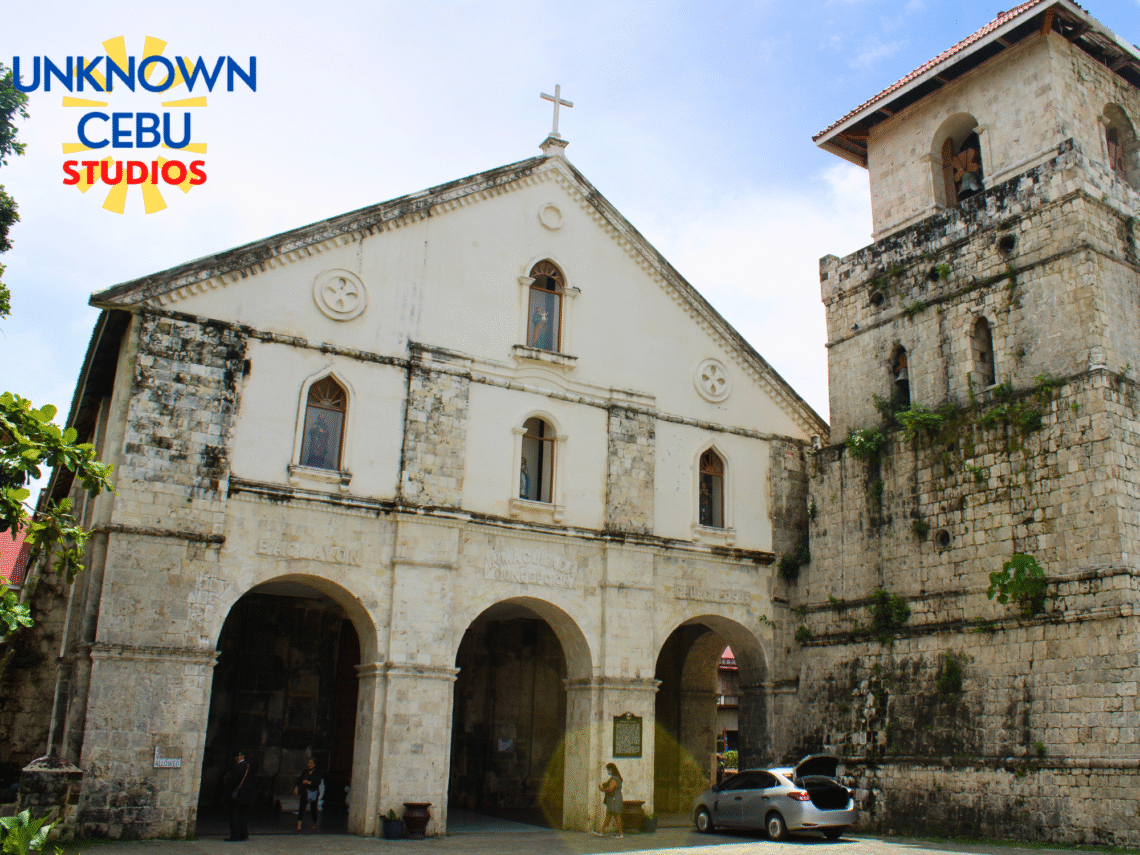

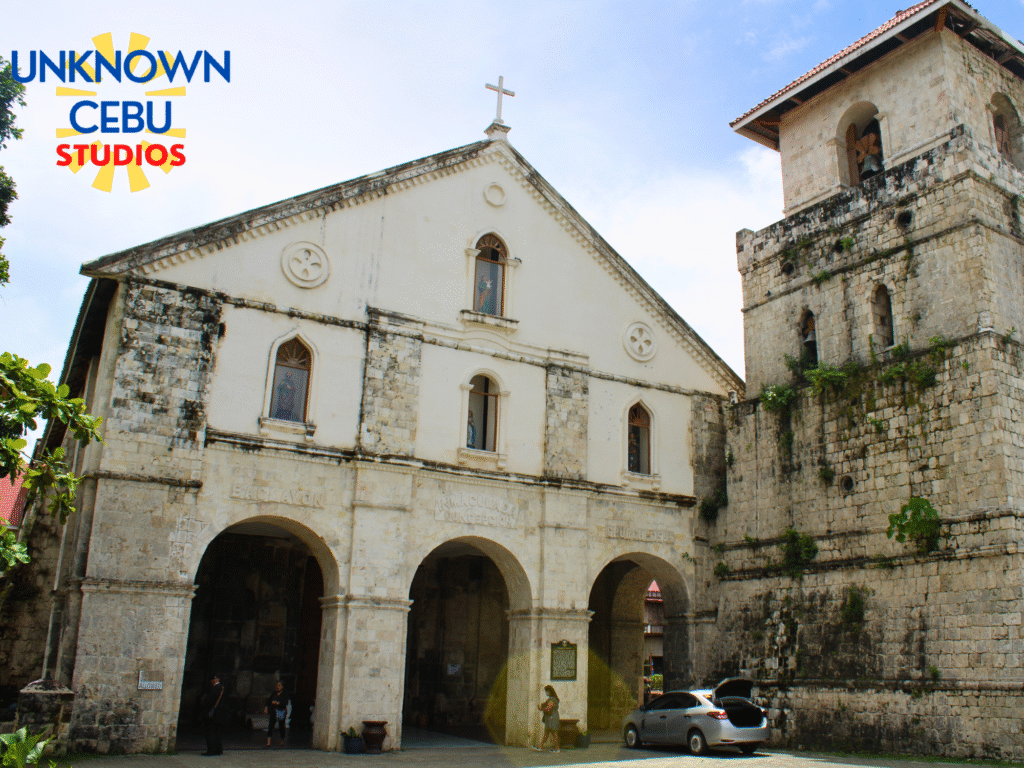

Just six kilometers east of Tagbilaran City lies a structure that is far more than a place of worship; it is a calcified chronicle of the Visayas, a fortress disguised as a sanctuary, and a testament to the sheer grit of the Boholano spirit. The Immaculate Conception Parish , often simply called the Baclayon Church, demands a reverence that goes beyond its religious function. Designated as both a National Cultural Treasure and a National Historical Landmark, this “Coral Citadel” stands as one of the oldest stone churches in the Philippines, its foundations steeped in a history that dates back to the arrival of Jesuit missionaries Fr. Juan de Torres and Fr. Gabriel Sánchez in 1596. When you stand before its imposing facade today, you aren’t just looking at a church; you are looking at the frontline of the 17th-century “Moro Wars,” where the architecture itself—the “Fortress Baroque”—was designed to repel slave raiders from the southern sultanates just as much as it was built to save souls.

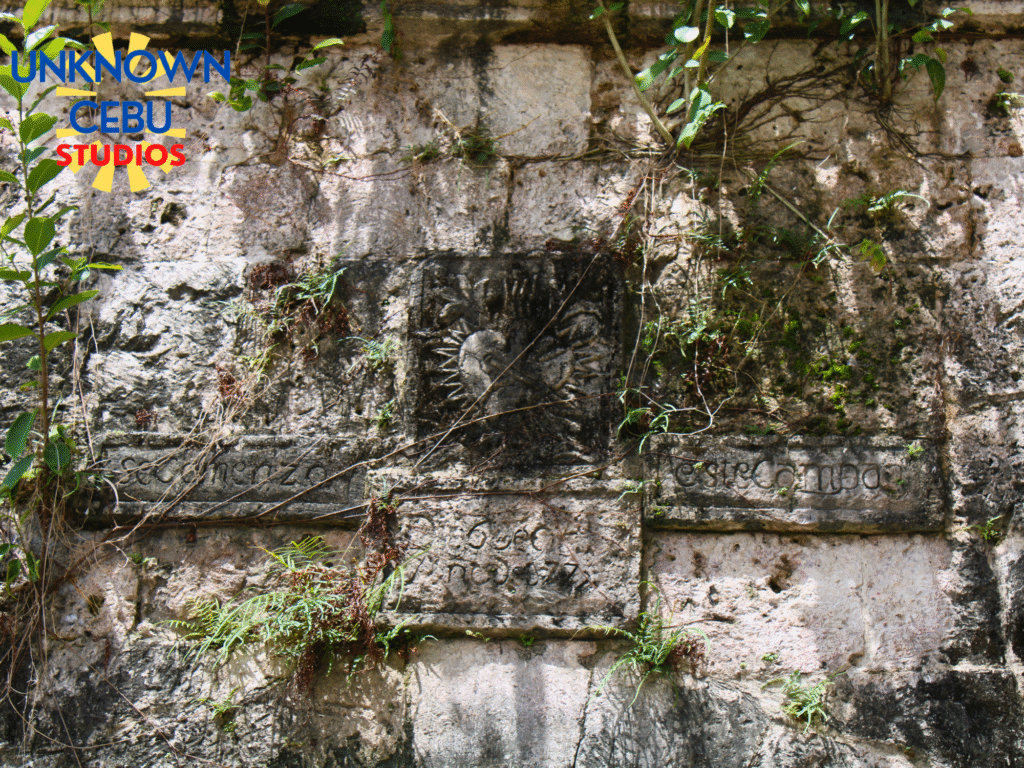

The walls of Baclayon whisper stories of a time when faith required physical fortification. The transition from temporary thatch to the permanent masonry we see today began in 1717, a monumental decade-long undertaking that mobilized the polo y servicio system to harvest coral stones from the adjacent sea. These stones were cut into square blocks and bound together using a technique that has fascinated engineers and foodies alike. Local oral history has long claimed that millions of egg whites were used to create the lime mortar, a hydrophobic binder that made the walls impervious to the elements. Science has finally caught up with tradition; chemical analysis has detected proteinaceous amine groups in the mortar, confirming the presence of albumin. This immense construction project inadvertently birthed a sweet legacy: the leftover yolks were used by the women of the parish to create broas, leche flan, and torta, establishing a culinary tradition that sustains the livelihood of Baclayon to this day.

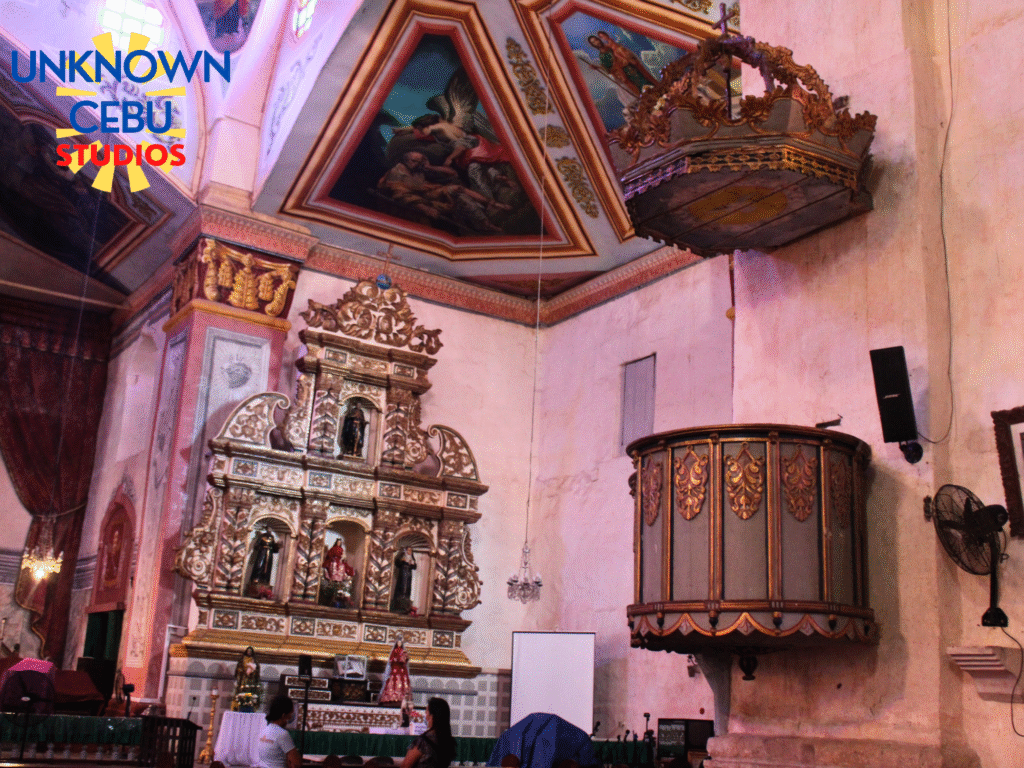

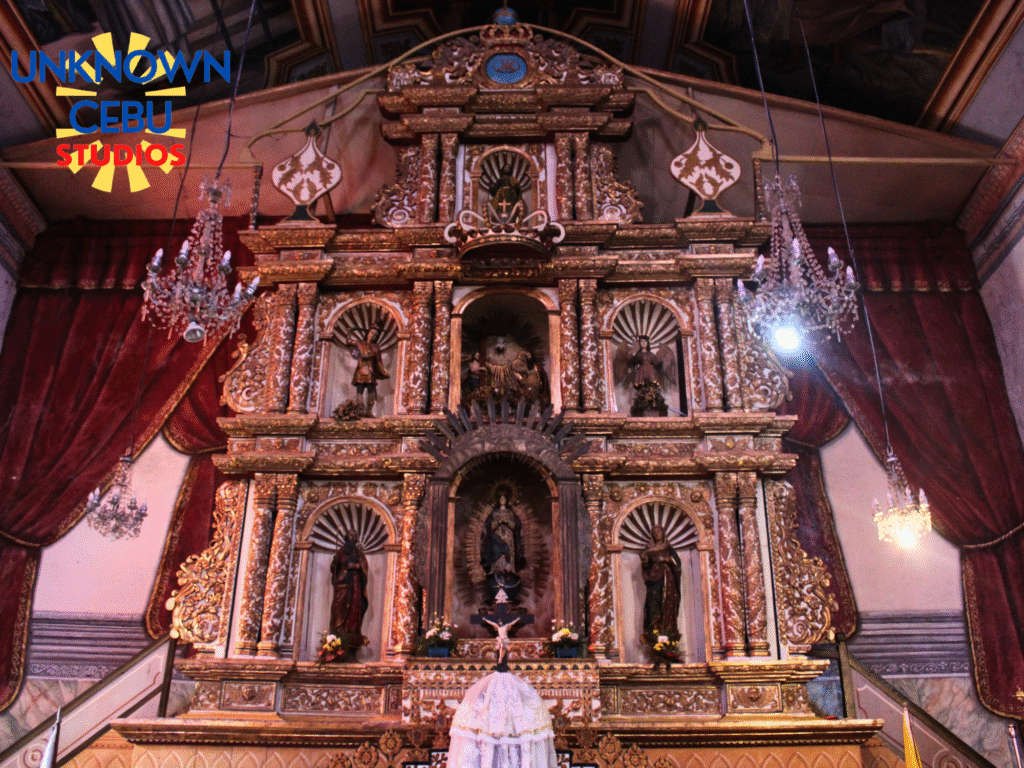

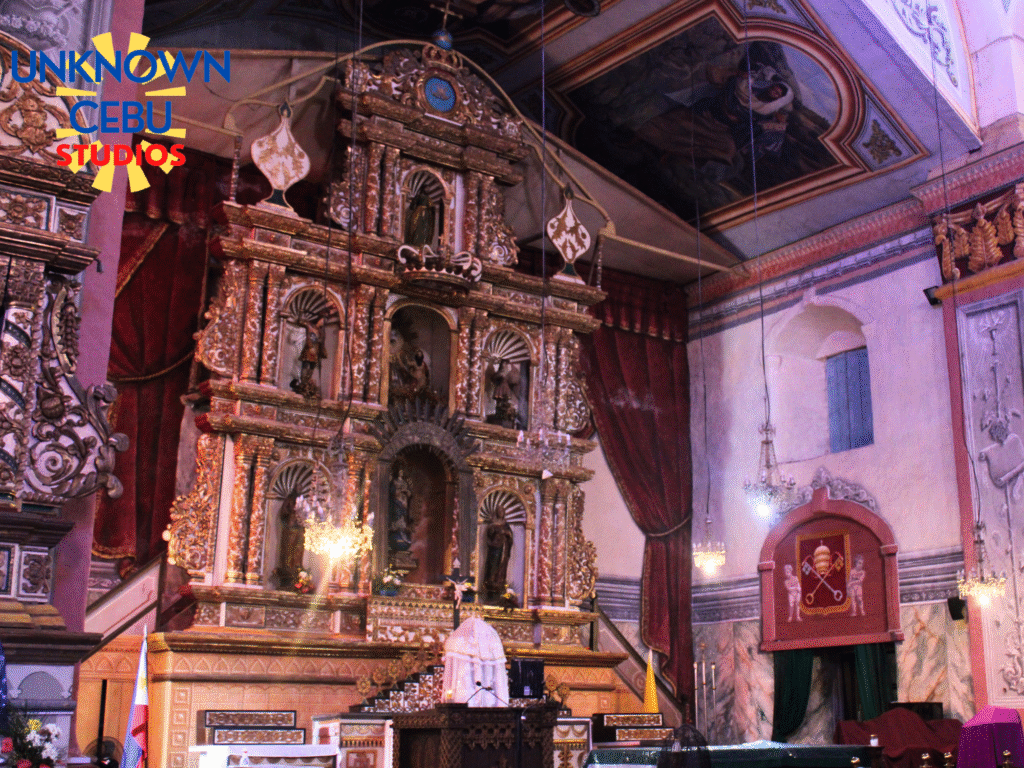

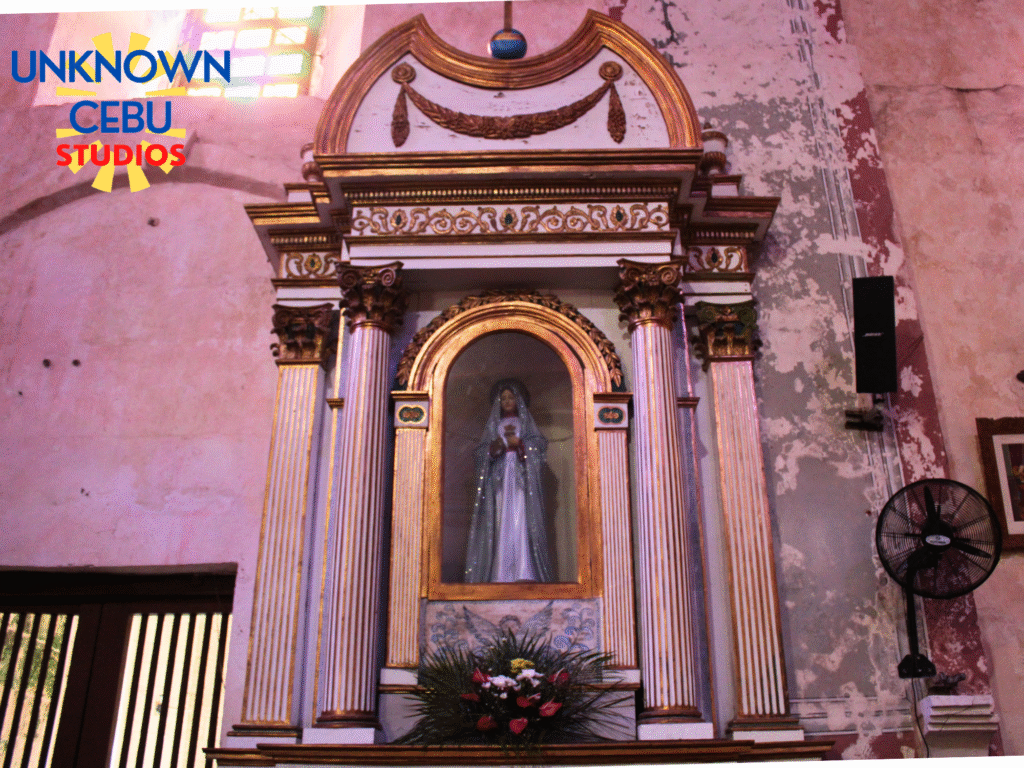

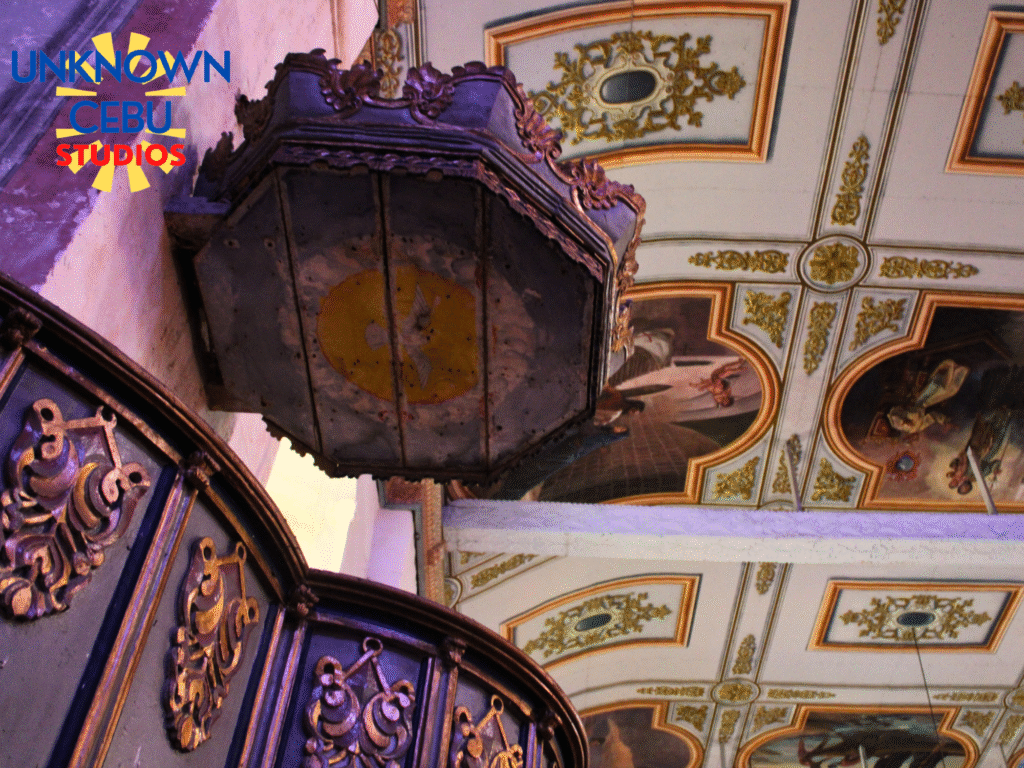

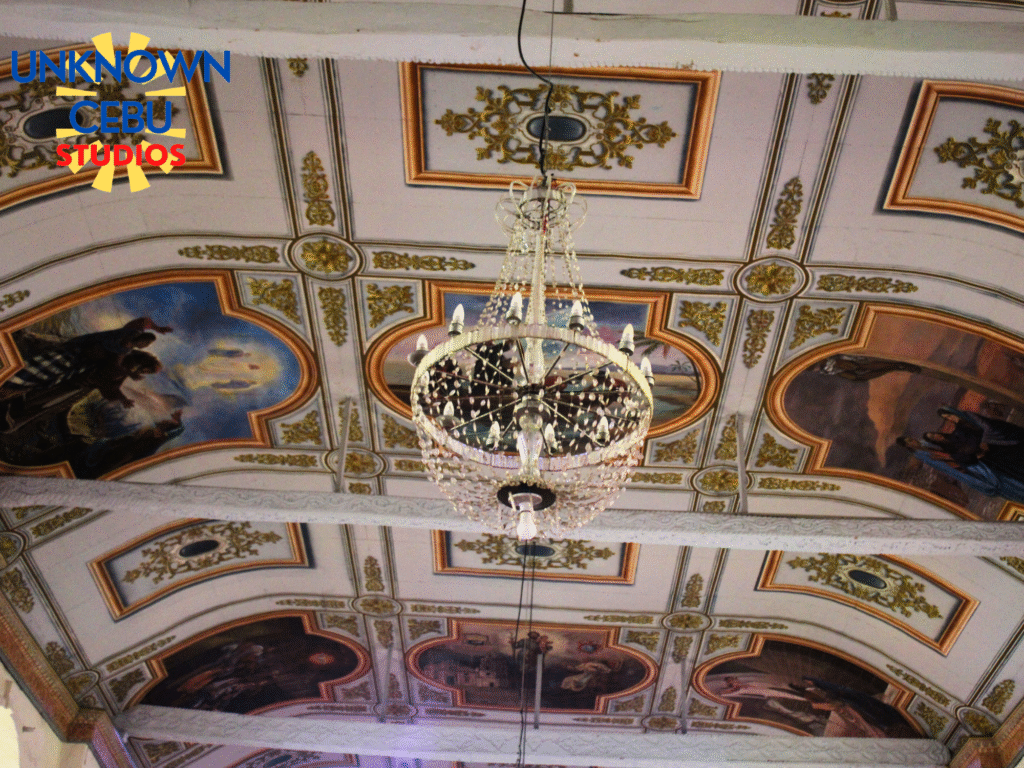

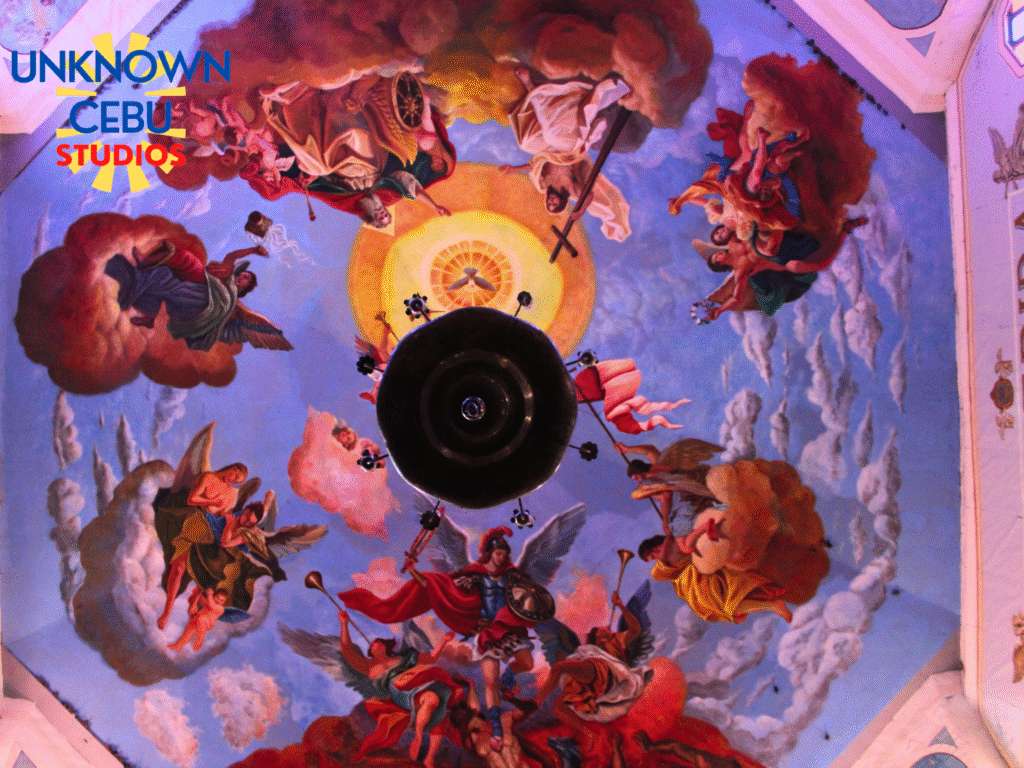

Following the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1768, the Augustinian Recollects took the reins, softening the severe military aesthetic of the Jesuits with Neoclassical refinements. It was under their watch, particularly Fr. José María Cabañas in the late 19th century, that the church received its iconic portico and the bell tower was fully realized—built as a separate structure to prevent it from crushing the nave during tremors. Inside, the church is a treasury of colonial art. The Museo Parroquial housed in the convento displays ivory santos, massive sheepskin cantorals that required an entire choir to read, and the gilded Baroque retablos that shimmer in the tropical light. High in the loft sits a pipe organ from 1824, restored to its full glory, its notes once again filling the cavernous nave with music that has echoed here for nearly two centuries.

However, the narrative of Baclayon is also one of profound vulnerability. The date October 15, 2013, is etched into the memory of every Boholano. At 8:12 AM, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake unleashed the energy of 32 Hiroshima bombs, bringing the bell tower and the 19th-century portico crashing down in a cloud of white dust. It was a heartbreak for the community, a shattering of their cultural identity. Yet, the emptiness of the church during the holiday of Eid al-Adha was a small mercy that prevented a mass casualty event; one asks what sort of tragedy could have happened if the earthquake occurred during an important event,. The subsequent restoration, a massive multi-year effort by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, became a battleground of philosophy. When the church was unveiled in 2018, its gleaming, cream-colored lime plaster shocked those used to the “romantic ruin” look of exposed stone. But this “whitewash” was historically accurate—a protective skin meant to save the porous coral from rotting away, a decision that prioritized the building’s survival over modern aesthetics.

Today, the Baclayon Church stands restored, its scars healed but not forgotten. It remains on the Tentative List for UNESCO World Heritage status, a recognition of its precarious yet enduring value. But beyond the accolades and the tourists, it remains the beating heart of the town, especially during the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. From the dungeon beneath where punishments were once meted out, to the soaring heights of the rebuilt tower, Baclayon is a complex paradox of colonial imposition and indigenous resilience. It is a place where the stone breathes, where the mortar tastes of history, and where the bells, once silenced by the earth itself, ring out again over the Bohol Sea.

Ultimately, the true measure of the Baclayon Church is not found in its UNESCO nomination or its status as a National Cultural Treasure, but in its stubborn refusal to become a mere relic. It remains a living, breathing entity. Every morning, the bells still toll for the faithful, just as they did when watchmen scanned the horizon for raiders. The recent restoration, with its controversial coat of fresh lime, is not an erasure of history but a necessary act of love—a promise that this structure will endure for another three centuries. It forces us to confront a difficult truth about heritage: that preservation is not about freezing time, but about managing change to ensure survival.

As you leave the complex, perhaps buying a bag of broas from a nearby vendor, realize that you are consuming history in its most tangible form. That sweet, crumbling pastry is the direct descendant of the mortar that holds the church together, a delicious cycle of sustainability that predates modern environmentalism. Baclayon stands as a challenge to us all. It asks us to be better custodians of our past, to look beyond the surface aesthetics, and to recognize that our identity is built on foundations as complex, fragile, and resilient as coral stone.

Sources:

“Study on the Seismic Response of Baclayon Church, Bohol, Philippines.” Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage 17, no. 1 (2017): 495–506. conservation-science.unibo.it/article/view/7164.

Estacio, F. P., B. T. D. C. Abasolo, and E. A. P. D. Marasigan. “The Baclayon Church, Bohol: Debris of Mortar – A Geomaterial Dimension of a Philippine Historical Church (presentation).” ResearchGate, August 2019. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32766.13129.

Estacio, F. P., B. T. D. C. Abasolo, and E. A. P. D. Marasigan. “The Baclayon Church, Bohol: Debris of Mortar – A Geomaterial Dimension of Philippine Cultural-Historical Church.” ResearchGate, August 2019. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.14811.23849.

Oballo, M. L. “Assessment of the Cultural Heritage Significance of the Baclayon Church Complex after the 2013 Bohol Earthquake.” De La Salle University Animo Repository, 2017. animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/faculty_research/4055/.

“Baclayon Church.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre Tentative List, October 19, 1993. whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/3860/.

“2013 Earthquake Rehabilitation Plan.” Provincial Planning and Development Office, Bohol. Accessed November 30, 2025. ppdo.bohol.gov.ph/plan-reports/development-plans/2013-earthquake-rehabilitation-plan/.

“Destruction of heritage churches lamented.” INQUIRER.net, October 15, 2013. newsinfo.inquirer.net/507871/destruction-of-heritage-churches-lamented.

“P650M seen restoration cost.” INQUIRER.net, March 10, 2014. newsinfo.inquirer.net/580127/p650m-seen-restoration-cost.

“Baclayon’s pipe organ plays beautiful music…again.” Philstar.com, December 14, 2008. philstar.com/cebu-lifestyle/2008/12/14/423532/baclayons-pipe-organ-plays-beautiful-musicagain.

“Egg whites, egg yolks and cultural heritage preservation.” Philstar Life. Accessed November 30, 2025. philstarlife.com/geeky/603282-egg-whites-egg-yolks-cultural-heritage-preservation.

“Baclayon Church.” Municipality of Baclayon, Bohol – Official Website. Accessed November 30, 2025. baclayon.bohol.gov.ph/baclayon-church/.

“Museo Parroquial de Baclayon.” Municipality of Baclayon, Bohol – Official Website. Accessed November 30, 2025. baclayon.bohol.gov.ph/museo-parroquial-de-baclayon/.

“Baclayon Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified November 15, 2025. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baclayon_Church.

“Baclayon Church.” Wikiwand. Accessed November 30, 2025. wikiwand.com/en/articles/Baclayon_Church.

“Baclayon Church: Heritage & Architecture.” Bohol-Philippines.com. Accessed November 30, 2025. bohol-philippines.com/baclayon-church-heritage-architecture/.

“Baclayon Church – 300 Years of Faith.” Bohol-Philippines.com. Accessed November 30, 2025. bohol-philippines.com/baclayon-church-300-years-faith/.

“Baclayon Church.” Experience Bohol. Accessed November 30, 2025. experiencebohol.com/baclayon-church/.

“Immaculate Conception Church – Baclayon.” ORGPH. Accessed November 30, 2025. orgph.com/locations/immaculate-conception-church-baclayon.

“Baclayon Church: 3 Years After the Earthquake.” Miscellaneous Strings (blog), March 15, 2017. miscellaneastrings.wordpress.com/2017/03/15/baclayon-church-3-years-after-the-earthquake/.

“Baclayon Church.” Baclayon Church (blog). Accessed November 30, 2025. baclayonchurch.wordpress.com/.

Flordeliza Delfin. “Body.” Flordeliza Delfin (blog). Accessed November 30, 2025. flordelizadelfin.home.blog/body/.