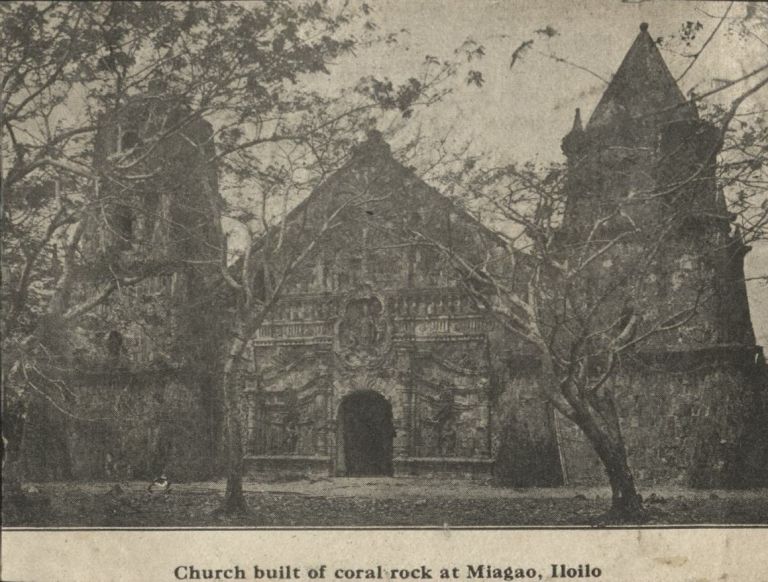

The history of Miagao, Iloilo, is often narrated through the epic scale of its Miagao Fortress Church, a UNESCO masterpiece completed in 1797. Yet, a short distance away, another, less-heralded stone sentinel stands as a crucial physical link to the town’s evolution from a simple administrative post to a commercial nerve center: the Taytay Boni, formally known as Puente de Boni. This structure, whose name literally translates to “Boni’s Bridge,” is explicitly recognized as the oldest standing Spanish bridge in the municipality, and its completion in 1854 is a significant chronological marker. It represents the colonial shift in focus from the grand, 18th-century Ecclesiastical Building Period (the churches) to the pragmatic, 19th-century Commercial Infrastructure Period (roads and bridges), using the same local technology to fulfill new secular, economic demands.

The choice of construction material and technique for Taytay Boni firmly anchors it in the legacy of the fortress-builders. The bridge was built using massive yellow coral stone slabs, known locally as tablea, quarried from the mountains of Igbaras and Miagao. Critically, these are the exact same distinctive coral stones used to construct the great Miagao Church, establishing a clear architectural and material lineage between the 1797 edifice and the 1854 bridge. This continuity demonstrates that the sophisticated, regional system for quarrying and masonry, originally developed by the friars, had been successfully adapted and standardized for major secular public works. Completed under the local executive, Governadorcillo Miguel Navales, the bridge established a stable transport connection along the primary coastal route, stabilizing regional trade and setting a vital, calculated precondition for the massive commercial transformation that was about to engulf Panay Island.

Taytay Boni’s precise date of 1854 is essential because it places the investment significantly before the rapid acceleration of the sugar industry, catalyzed by Nicholas Loney in the 1860s. This was not reactive infrastructure built to accommodate existing traffic; it was a foundational, strategic commitment to solidify and expand the recovering Port of Iloilo’s commerce. The structure itself is a relatively small, narrow bridge, measuring about 36.4 meters long by 8.4 meters wide. This scale was designed for the lighter load and narrow profile of horse-drawn carriages, the principal means of colonial transport at the time. Despite its utilitarian purpose, the bridge exhibits a remarkable ornamental elegance, defined by its most salient feature: massive newel posts topped by pyramidion finials, giving the entryway the formal aesthetic of a colonial monument.

Like virtually all public works in the Spanish Philippines, the bridge carries a profound and enduring association with the human cost of colonial exploitation. It was constructed through the system of polo y servicio or forced labor, where local Filipinos were conscripted without pay. The coercive nature of the work was enforced by the ever-present supervision of the guardia civil. Yet, within this regime of exploitation lies the bridge’s most unique cultural distinction: its name. The common and officially recognized name, Taytay Boni, honors Bonifacio Neular, the native maestro de obra or construction foreman who supervised the building process. The institutional preservation of a Filipino craftsman’s name, both in local records and in enduring oral tradition, is a rare and significant act of recognition in colonial history, highlighting that the sound architecture and structural integrity were ultimately the result of native expertise.

The bridge’s resilience was severely tested long after the Spanish were gone. After remaining a highly functional artery throughout the American period and World War II, the structure suffered partial damage in 1948 when a powerful Magnitude 8.2 earthquake struck the province. Although stone slabs were loosened and a section of wall crumbled, the bridge’s massiveness and superior load-bearing capacity—a hallmark of the colonial-era heavy construction—prevented its complete destruction, validating the durability of the engineering style. Today, located in Barangay Guibongan at “Crossing Kamatis,” it has transitioned from a critical highway link to a beloved historic landmark and tourist attraction, albeit one in need of structural intervention to repair the damage from the seismic event.

Taytay Boni also offers an instructive comparison to its younger neighbor, the Puente de Britanico (c. 1873), which is located just 2 km south. Taytay Boni’s narrow, elegant design and yellow stone predate the sugar boom; the younger, grander, and more massive Puente de Britanico, built nearly two decades later with different white stone and a Roman Arch design, was a direct functional response to the heavier, higher-volume traffic—specifically, the need to support the greater weight of bulk sugar cart haulage. Taytay Boni was the essential foundation of the road network; Puente de Britanico was the necessary upgrade. This chronological progression in bridge engineering standards mirrors the rapid evolution and ascent of Iloilo to global economic prominence. Despite the older bridge’s unique historical seniority and material link to the UNESCO church, it still lacks an official NHCP national heritage declaration, a critical step to ensure the restoration and stabilization of this dual symbol of colonial coercion and Filipino craftsmanship.

|UnknownCebu|

Sources:

Funtecha, Henry Florida, and Melanie J. Padilla. Historical Landmarks and Monuments of Iloilo. Iloilo City, Philippines: Visayan Studies Program, U.P. in the Visayas, 1987.

Ortigas Foundation Library. “Image Bank Database.” Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.ortigasfoundationlibrary.com.ph/collections/image-bank-database?search=Miagao.

Municipality of Miagao. “Puente de Boni.” Miagao History. September 25, 2017. https://www.miagao.gov.ph/about-miagao/miagao-history/puente-de-boni/.

Matias, Jonathan R. “Miag-ao History.” Sulugarden. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://sulugarden.com/articles/blog/miag-ao-history/.

Matias, Jonathan R. “Puentes de España: A Tale of Two Bridges.” Sulugarden. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://sulugarden.com/puentes-de-espana-a-tale-of-two-bridges/.

Guide to the Philippines. “Taytay Boni.” Guide to the Philippines. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://guidetothephilippines.ph/destinations-and-attractions/taytay-boni.

Silverbackpacker. “Taytay Boni Miagao.” Silverbackpacker. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://silverbackpacker.com/taytay-boni-miagao/.

iloveiloilo. “Taytay Boni: Pls Don’t Call it a Spanish Bridge.” i love iloilo. March 28, 2007. https://iloveiloilo.wordpress.com/2007/03/28/taytay-boni-pls-dont-call-it-a-spanish-bridge/.

Scribd Uploader. “Brief History of Miagao.” Document uploaded to Scribd. Accessed November 23, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/140742013/Brief-History-of-Miagao.

Miagao Tripod Site. “Motif.” Accessed November 23, 2025. https://miagao.tripod.com/church/motif.htm.