For the curious traveler stepping off the ferry at Siquijor Port 1, the immediate greeting is not a sign for a resort, but the formidable, austere silhouette of the Saint Francis de Assisi Parish Church. While its younger, more ornate sister in Lazi often steals the heritage spotlight, the Siquijor Church—founded in 1783—holds a much deeper, more consequential secret. It is not just the island’s oldest church; it is the foundational colonial nexus that physically and administratively defined the entire province. When the Spanish established this complex, they weren’t just building a place of worship; they were implanting the very anchor of their administrative and geopolitical project, choosing a site strategically facing the Cebu Strait to project immediate authority upon every arrival. Before this 1783 founding, Siquijor was the mystical Kingdom of Katugasan, the “Island of Fire” renowned for its firefly-lit tugas (Molave) trees (though this is probably myth with some inkling of truth). The church, alongside the first municipality, became the physical center of the colonial reducción, forcing dispersed populations into one supervised, manageable community, and thus, drawing the first political map of the island.

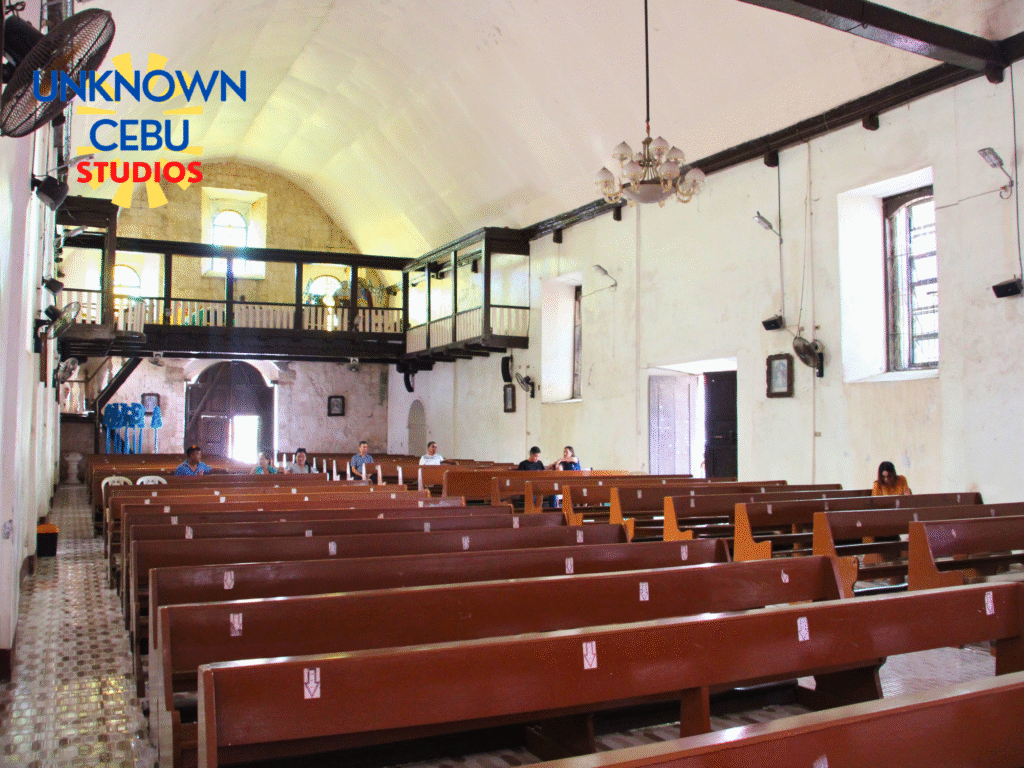

The sheer, protracted effort required to transition this vision from a temporary nipa hut to an enduring stone bastion tells a compelling story of colonial struggle in the periphery. While the parish was formally established in 1783, the permanent construction—using rough, whitish coral stone and stone rubble fill—spanned a monumental 36 years, from 1795 to 1831. This decades-long timeline, contrasting sharply with the faster builds in wealthier centers, is material evidence of the chronic logistical nightmares, funding constraints, and the immense, sustained toll of forced polo y servicio (communal labor) on the local Siquijodnons. Initially overseen by secular clergy from the Diocese of Cebu, the project was inherited and completed by the powerful Augustinian Recollects (OAR), who subsequently used this “Madre Parish” as their sole administrative base. For over five decades (1783–1836), this church was the only Catholic structure on the island, serving as the singular locus for all spiritual, legal, and educational life, underscoring its absolute institutional dominance before the first ecclesiastical division occurred in Larena in 1836.

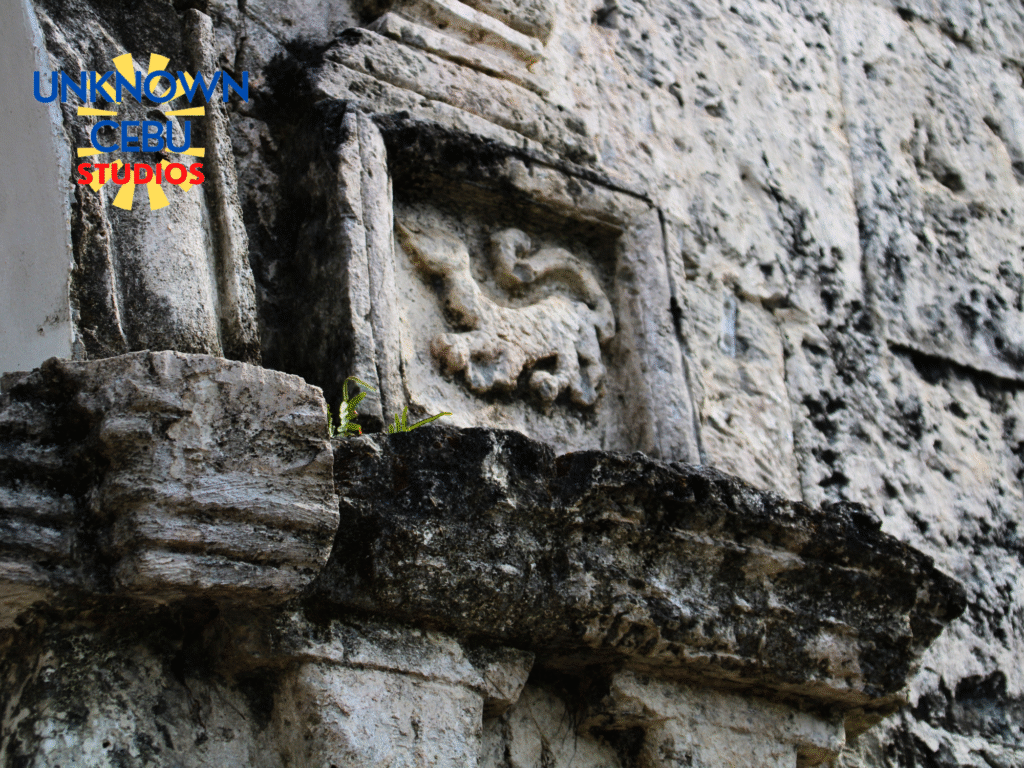

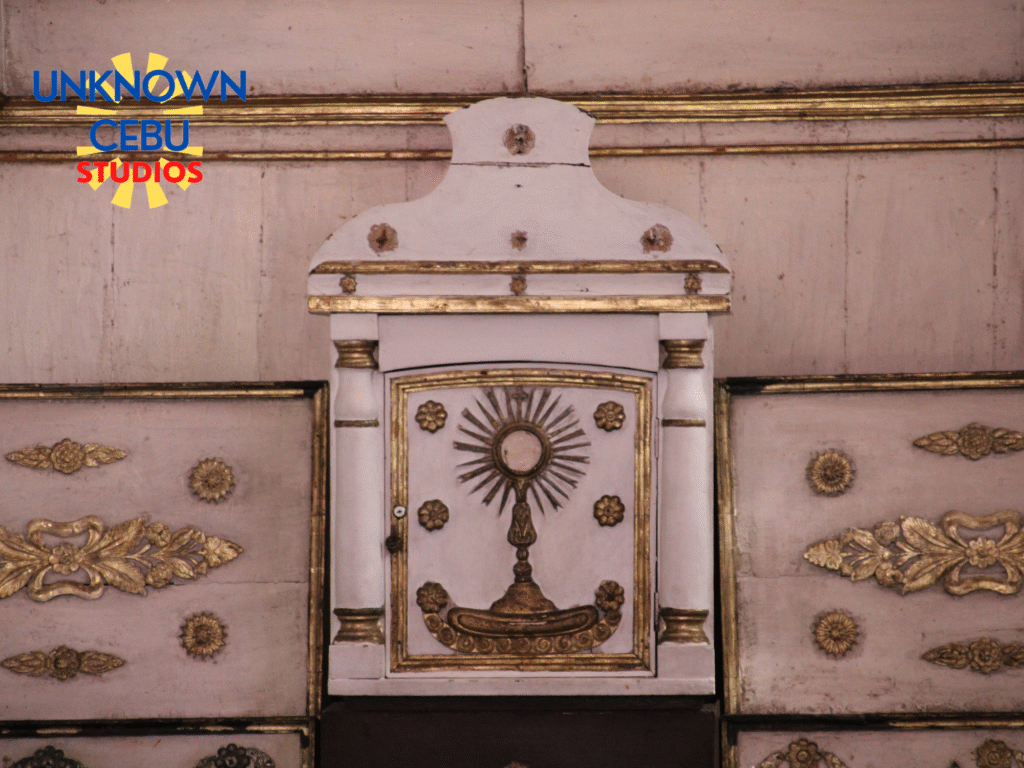

A closer look at the architecture reveals that the complex was less a grand temple and more a “Trinchera de la Fe” (Trench of Faith)—a hardened defensive citadel vital for survival against persistent 19th-century maritime threats. The complex is deliberately tripartite: the robust main church, the adjacent, fortress-like Convento (Parish House) built of stone rubble that served as a refuge for residents during raids, and the most compelling feature, the independent adobe Bell Tower. The belfry was not integrated into the façade but was strategically placed on a small, elevated hill about 20 meters away, functioning as a dedicated watchtower for spotting pirates. Crucially, this essential defensive structure was not completed until 1891, six decades after the main church and right on the eve of the Philippine Revolution. This late completion dramatically proves that the threat of piracy was not a relic of the past but a sufficient, persistent security risk that necessitated final investments in defensive infrastructure at the capital complex just before the colonial collapse.

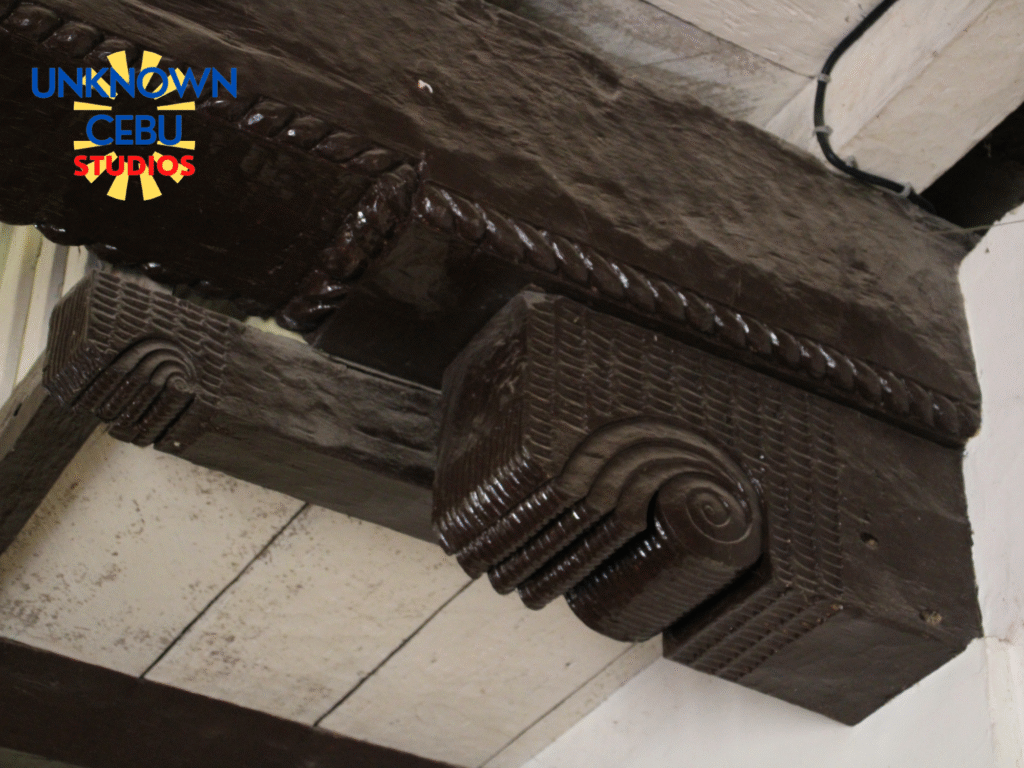

The church’s history is a relentless record of resilience. Its simple, massive stone construction—characterized by “minimal décor” and austerity—prioritized durability over opulence, a pragmatic choice that allowed it to survive the upheavals of the Philippine Revolution, the Philippine-American War, and the ferocious conflicts of the Second World War, remaining the critical nucleus when external governance failed. Furthermore, its engineering, which notably includes wooden panels for the pediments (the façade’s triangular top section), suggests a clever, built-in seismic adaptation to reduce weight and better resist the frequent tremors that constantly threaten coral stone structures across the Visayas. The church’s structural integrity, allowing it to remain functionally active despite being built of rough stone rubble in a zone of chronic seismic and meteorological instability, is a testament to superior, necessity-driven colonial engineering.

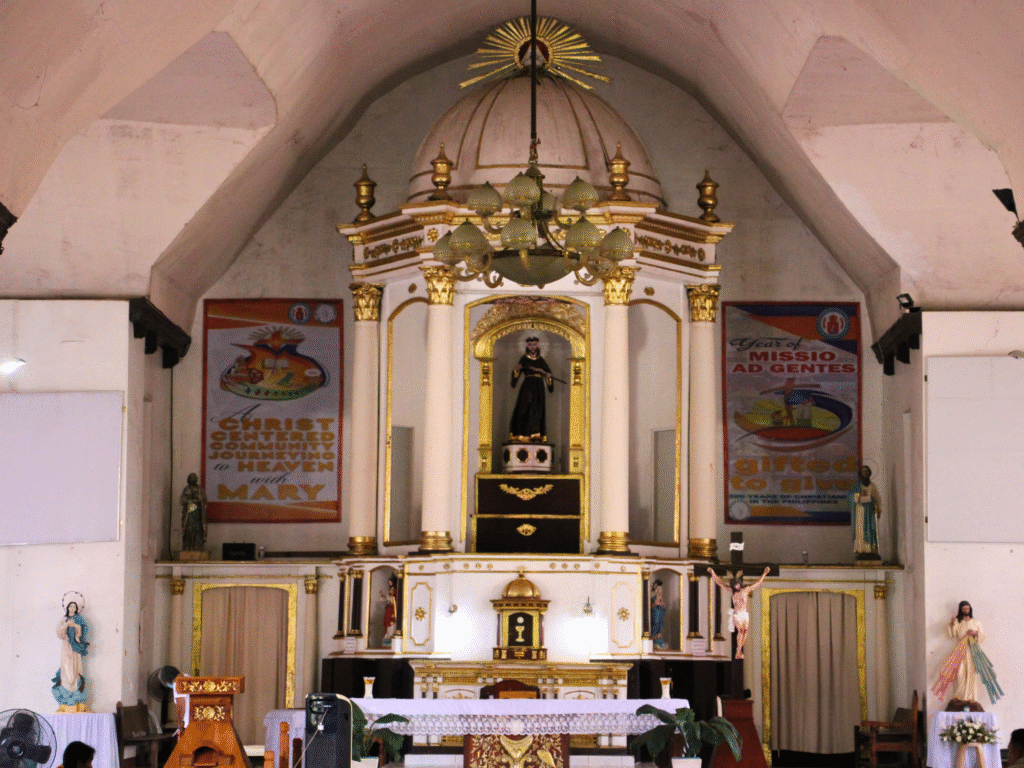

However, the most profound and unique legacy of the St. Francis de Assisi complex is its role as the cultural nexus where orthodox Catholicism and Siquijor’s potent, indigenous mystical traditions seamlessly collide. Despite the island’s global notoriety for traditional healing (mananambal) and powerful beliefs, approximately 95% of the population are Roman Catholic. For Siquijodnons, this is not a contradiction, but a pragmatic syncretism. The physical church structure itself has been co-opted and functionally integrated into folk healing: Holy Water, sourced directly from the church, is a vital, acknowledged ingredient in traditional preparations, such as the tuob/palina ritual. By utilizing the church’s Holy Water, mananambal effectively transfer the potent blessings and institutional legitimacy of the Catholic Church onto their folk remedies, ensuring acceptance from a deeply Catholic populace.

The cultural integration culminates during Holy Week, formalized as the “Healing Festival,” where healers gather and plant collectors (mangangalap) collect ingredients from spiritually potent sites—the forest, caves, cemeteries, and, tellingly, the church grounds. This final point confirms that the St. Francis de Assisi Parish Complex functions as the ultimate symbolic meeting point of the island’s spiritual worlds. While its sister church, Lazi, may boast the title of National Cultural Treasure, the Siquijor Church stands as the undisputed definitive origin point—a formidable, austerity-driven coral bastion that has successfully endured every external conflict and internal challenge, transforming from a mere colonial outpost into the indispensable, living nexus of Siquijodnon identity, history, and spiritual duality.

Sources:

Cuesta, Angel Martinez. “Augustinian Recollect History of Siquijor (1794-1898).” Philippine Social Science Journal 2, no. 2 (2019). https://philssj.org/index.php/main/article/view/87.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Lazi Church Complex.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre Tentative Lists. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/3860/.

ABS-CBN News. “In Siquijor, faith and mysticism mix during Holy Week.” ABS-CBN News, April 15, 2022. https://www.abs-cbn.com/life/04/15/22/in-siquijor-faith-and-mysticism-mix-during-holy-week.

Heritage Conservation. “Siquijor Church and Convent.” WordPress blog, July 27, 2006. https://heritageconservation.wordpress.com/2006/07/27/siquijor-church-and-convent/.

Siquijor History. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://www.siquijorhistory.org/.

“Lazi Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 20, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazi_Church.

Lakad Pilipinas. “Siquijor: St. Francis De Assisi Church.” June 27, 2012. https://www.lakadpilipinas.com/2012/06/siquijor-st-francis-de-assisi-church.html.

Siquijor Directory. “St. Francis of Assisi Church, Siquijor, Siquijor.” Accessed November 21, 2025. https://siquijordirectory.com/directory/stfrancisassisichurch/.

Siquijor Island Realty. “Churches in Siquijor.” Siquijor Island Realty. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://siquijorislandrealty.ph/churches-in-siquijor/.

Tita’s Travels. “Now You Know: Siquijor’s 6 Roman Catholic Churches.” WordPress blog, March 3, 2019. https://titastravels.wordpress.com/2019/03/03/now-you-know-siquijors-6-roman-catholic-churches/.

Ms. Oz Pinay. “Siquijor Churches.” WordPress blog, July 26, 2013. https://msozpinay.wordpress.com/2013/07/26/siquijor-churches/.

Castillon, Psyche. “Visita Iglesia in Siquijor.” April 17, 2025. https://psychecastillon.com/2025/04/17/visita-iglesia-in-siquijor/.

Scarlet Scribs. “The Mystical World of Siquijor.” WordPress blog, May 9, 2025. https://scarletscribs.wordpress.com/2025/05/09/the-mystical-world-of-siquijor/.

Pegarit. “Assisi Church.” WordPress blog. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://pegarit.wordpress.com/assisi-church/.

“File:Simbahan ng Siquijor NHI historical marker.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons. Last modified October 20, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simbahan_ng_Siquijor_NHI_historical_marker.jpg.

Anonymous. Untitled Document. Semantic Scholar. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f448/3636f76725867f3e0cb5976fdb02e45ac64c.pdf. Least Credible