There are houses, and then there are monuments—architectural anchors that refuse to be swept away by the river of history. In the heart of Jaro, Iloilo City, stands Casa Mariquit, officially the Javellana–Lopez Heritage House, a seemingly unassuming structure that is, in truth, an 1880s-1890s home of grand, yet understated proportions. Its date of construction is the key to its power, as it firmly establishes Iloilo’s status as a regional powerhouse after the legendary 1855 opening of the port that unleashed the flood of sugar wealth. While most historical narratives begin with the sugarcane boom, Mariquit’s existence compels us to look further back, proving that the earliest concentrations of Ilonggo capital were rooted in a pre-modern economy—the whispers of the prosperous textile trade and the establishment of Jaro as the undisputed ecclesiastical and administrative center. Named for Maria Salvacion Javellana, affectionately nicknamed “Mariquit” (meaning “beautiful”), this house is the chronological baseline for understanding Iloilo, providing the foundational legitimacy for the dynasties that would follow.

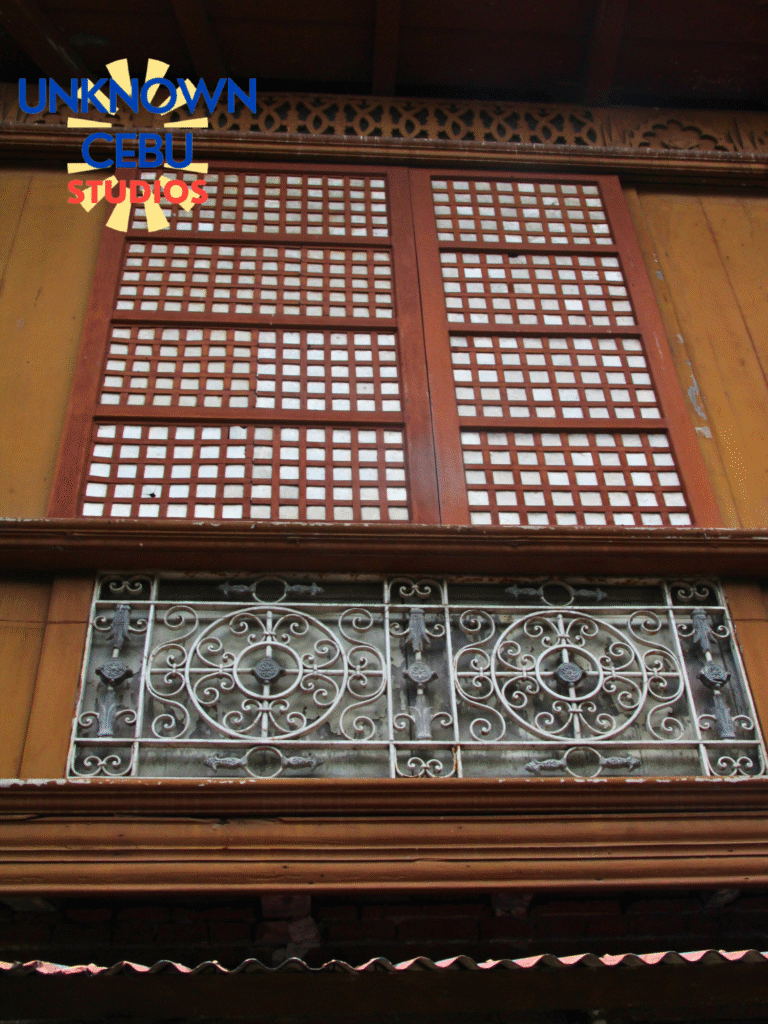

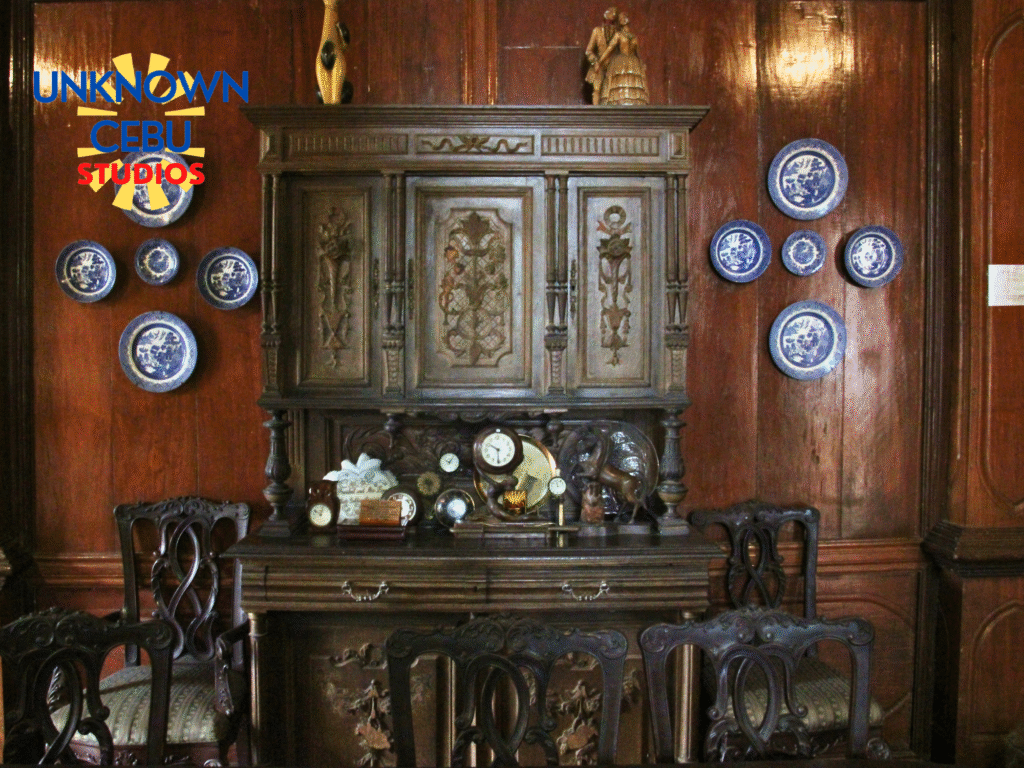

The founder, Ramon Javellana, was no mere hacendero but a banker and moneylender—the original “seed capitalist” who acted as the essential local financial intermediary. The architecture of the house, a sturdy bahay na bato constructed with expensive materials like tough, pest-resistant Molave and red brick, was not for lavish display, but for a singular, functional purpose: security. Casa Mariquit was deliberately built to function simultaneously as a private residence and a commercial banking headquarters, embodying a foundational duality where large-scale financial operations were deeply personalized and secured within the family household. The most tangible evidence of this ethic of functional prudence and resource consolidation is the cleverly concealed vault, installed circa 1910, hidden beneath the floorboards of the master bedroom. This fortress-like design, securing the family’s liquid capital in the most private space, reveals the fundamental modus operandi of early Ilonggo finance: prioritizing the safe containment of wealth over superficial decoration.

This functional architecture stands in stark contrast to the grandiloquence of the later Golden Age. Once the global sugar boom arrived, it birthed a new elite philosophy that replaced security with spectacle. While the 1803 Casa Mariquit employed indigenous durability, the mansions built in the next century, such as the Beaux-Arts Nelly Gardens (1928) or the Eclectic Lizares Mansion (1937), became vast, ornamental status symbols. These later structures, manifesting industrial and landed wealth, signaled a shift in aesthetic intent—from embodying capital security to manifesting visible status through European styling and immense scale. Casa Mariquit, described as “not as imposing as other houses,” thus serves as the crucial architectural baseline, silently affirming that the original wealth was established through quiet, personalized mercantile capital, which ultimately financed the explosive display of the succeeding sugar barons.

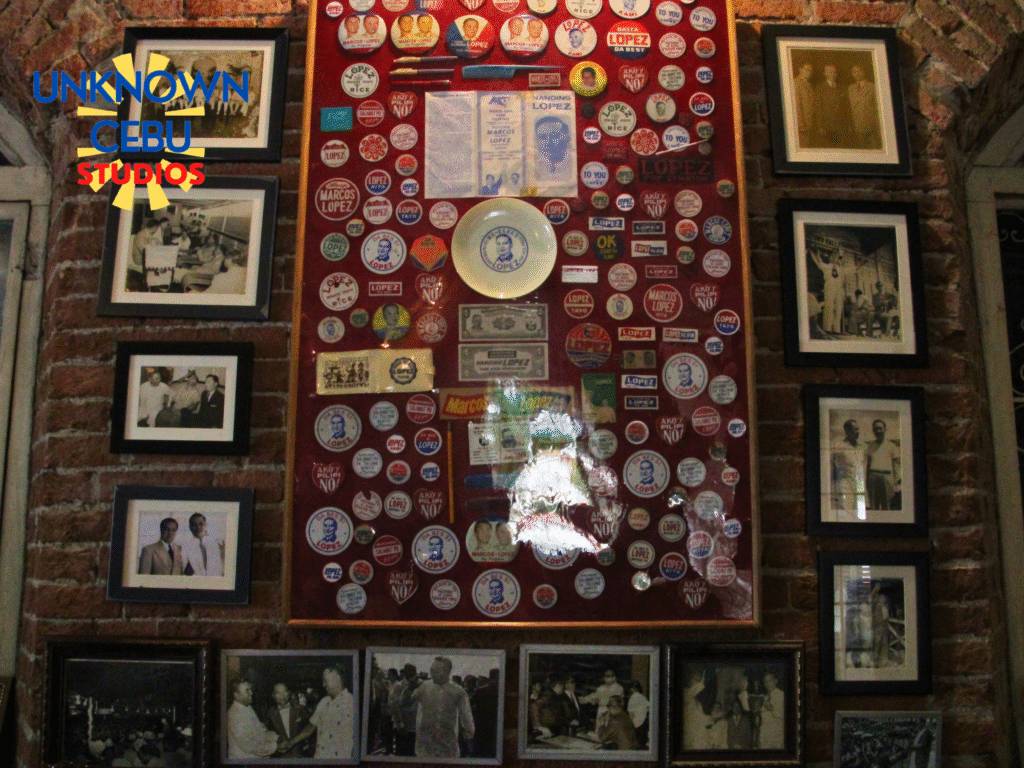

The two epochs of Iloilo’s elite were symbolically bridged by the 1918 strategic marriage of Mariquit Javellana to Fernando Lopez, Sr. This was more than a wedding; it was a deliberate dynastic merger that integrated the deep historical pedigree and localized legitimacy of the Javellanas with the burgeoning corporate and political power of the Lopez clan, retroactively anchoring the family’s media and utility wealth to the city’s ancient aristocratic roots. Following this union, the function of Casa Mariquit dramatically evolved. It transformed from a regional financial headquarters into the definitive regional Vice Presidential operational base during Fernando Lopez’s non-consecutive terms in office, serving as the essential anchor that secured continuous regional support for a dynasty primarily based in Manila. Here, the house shifted from securing land via debt consolidation to securing political influence and votes, a trajectory that saw it become a “center of social and political activity” that even preserved photographs of Lopez meeting international figures like Henry Kissinger.

Beyond the ledgers and political strategies, Casa Mariquit is also steeped in the profound cultural and spiritual dimensions of the region. The house features its own private Oratorio, underscoring the family’s adherence to the Catholic social structure, a faith connection that culminated in a singular global distinction: the residence was personally blessed by Pope John Paul II in 1981 during his visit to Iloilo. Perhaps even more captivating is the enduring local folklore of the subterranean tunnel said to link the house directly to the Jaro Cathedral belfry. Whether used for the clandestine transfer of Church assets by the founder or as a refuge during the Second World War, the tunnel’s persistent legend functions as a powerful, non-empirical metaphor. It suggests a cultural belief that the original banker wielded such immense, centralized power that he could physically bypass public space, reinforcing the mythos of the house as a bastion of secretive influence that transcended the surface world.

Today, the meticulous preservation of this historical nexus, largely under the stewardship of the family’s great-grandson, Robert Lopez Puckett Jr., has ensured its transition from a private domain to a public heritage asset. Declared a National Historical Landmark in 1993, Casa Mariquit operates as a living museum where visitors can examine period artifacts and experience the functional layout, learning about colonial-era social stratification and security concerns through the architecture itself. The preservation methodology, which pragmatically blends historical integrity with economic and ecological viability—even incorporating solar panels on the roof—offers a replicable model for sustainable heritage management. Casa Mariquit is therefore more than just the oldest house in Iloilo; it is a repository of two centuries of Ilonggo elite history, a secure fortress of capital, and a powerful symbol of the continuous, successful transition of wealth and power that continues to define the region’s contemporary narrative.

Sources: McCoy, Alfred W. (TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia) – Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal (Cambridge University Press)

Madrid, Randy M. (China and Asia: A Journal in Historical Studies) – Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal (University of the Philippines Research)

Priscilla Alma Jose vs. Ramon C. Javellana, et al. (G.R. No. 158239) – Primary Legal Document (Supreme Court of the Philippines)

Pedroso, John Erwin Prado. (BIMP-EAGA Journal for Sustainable Tourism Development) – Peer-Reviewed Academic Publication (ResearchGate/Journal)

Areno, Ephraim C. (“Chapter 3: The Family Tree of Lim Eung”) – Specialized Academic/Published Document (PACS.ph)

Villa, Hazel P. (Philippine Daily Inquirer) – Major National Newspaper (Signed Article)

Mawis, Arch. Vittoria Lou. (Philippine Daily Inquirer) – Major National Newspaper (Signed Article)

“For Iloilo’s Textiles: Innovation is Preservation.” (The Philippine Star) – Major National Newspaper (Unsigned Magazine Article)

“Casa Mariquit,” “Lopez Heritage House,” “López family of Iloilo,” “Fernando Lopez,” and “Jaro Belfry.” (All five Wikipedia articles) – Curated Encyclopedic Source

“DID YOU KNOW Philippine’s first “Millionaire’s Row” was in Jaro?” (Iloilo Business Park) – Commercial/Marketing Blog

“Eugenio López Sr.” (Grokipedia) – Unverified Wiki-style/User-Generated Content

“Javellana.” (Javellana: The blog) – Personal/Self-Published Blog

“Casa Mariquit Javellana Lopez.” (Wanderlog) – User-Contributed Travel Site

“Iloilo City moments.” (Trip.com) – User-Contributed Travel Site