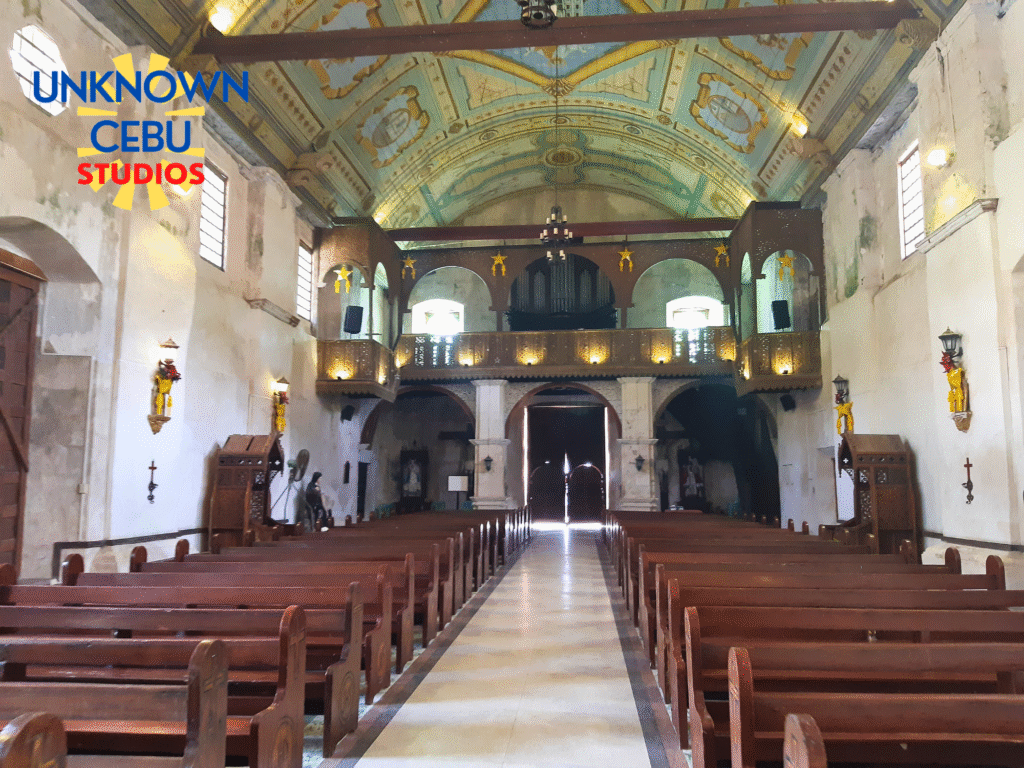

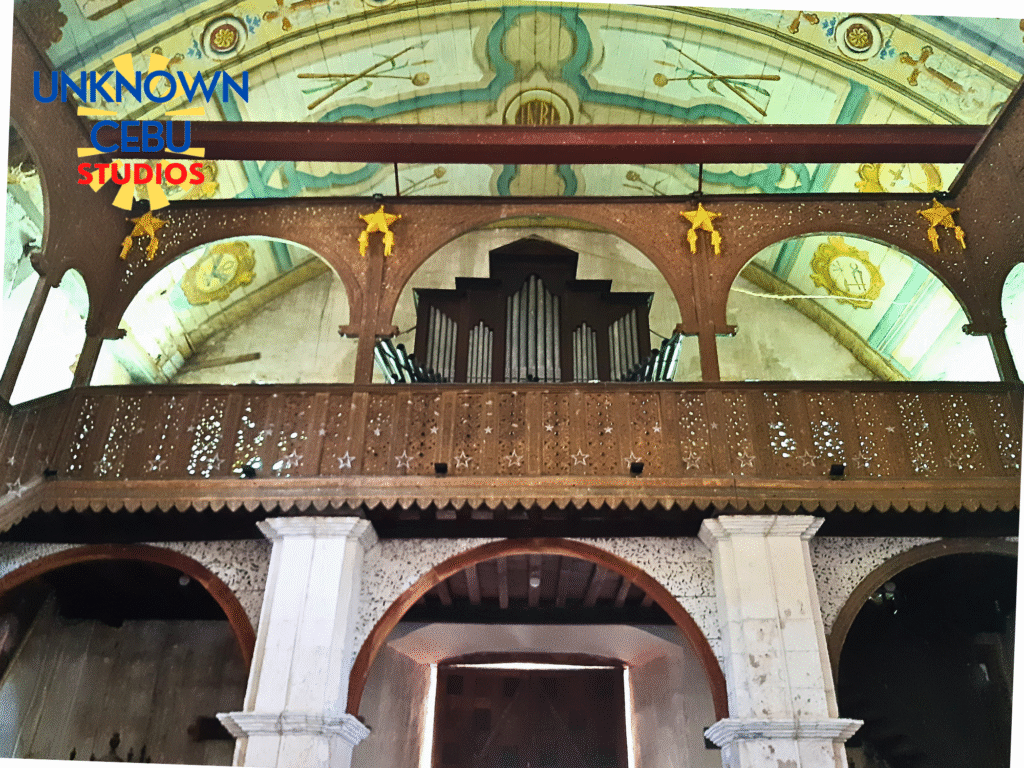

The pipe organ of Boljoon is more than just an instrument; it’s a National Cultural Treasure whose survival is a gripping tale of architectural defense, colonial politics, and relentless modern conservation. Nestled within the Archdiocesan Shrine of Patrocinio de María Santísima, this masterpiece is inextricably linked to the church’s identity as an iglesia-fortaleza (fortress-church). The massive coral stone walls and the 18th-century watchtower belfry—equipped with cannon ports—were built to defend against constant coastal raids. The decision by the Augustinians to install and protect a complex, costly European instrument like the organ, despite the ever-present military threat, powerfully signifies that liturgical and cultural grandeur were non-negotiable spiritual priorities. This organ is one of only three known surviving Spanish colonial pipe organs in Cebu, and a crucial piece of evidence in Philippine organology. Its proven identity links it to the Otorel family of Palencia, Spain—the same commercial firm responsible for the organs in Dalaguete and Maribojoc—confirming it as a product of the late-colonial drive for standardization.

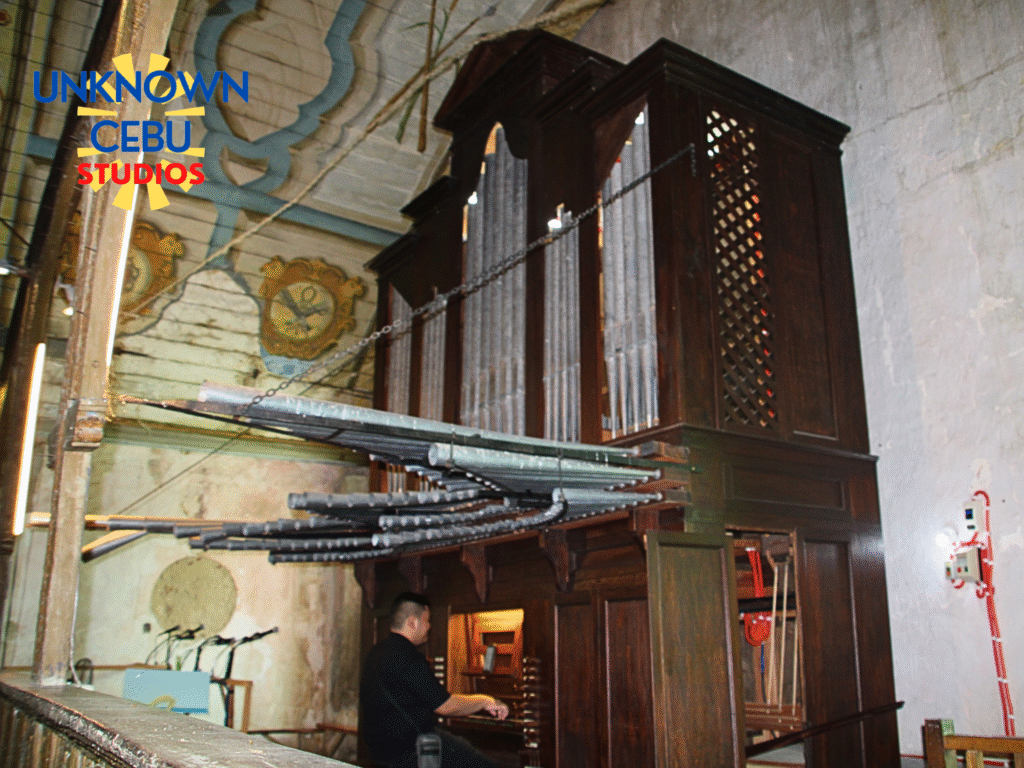

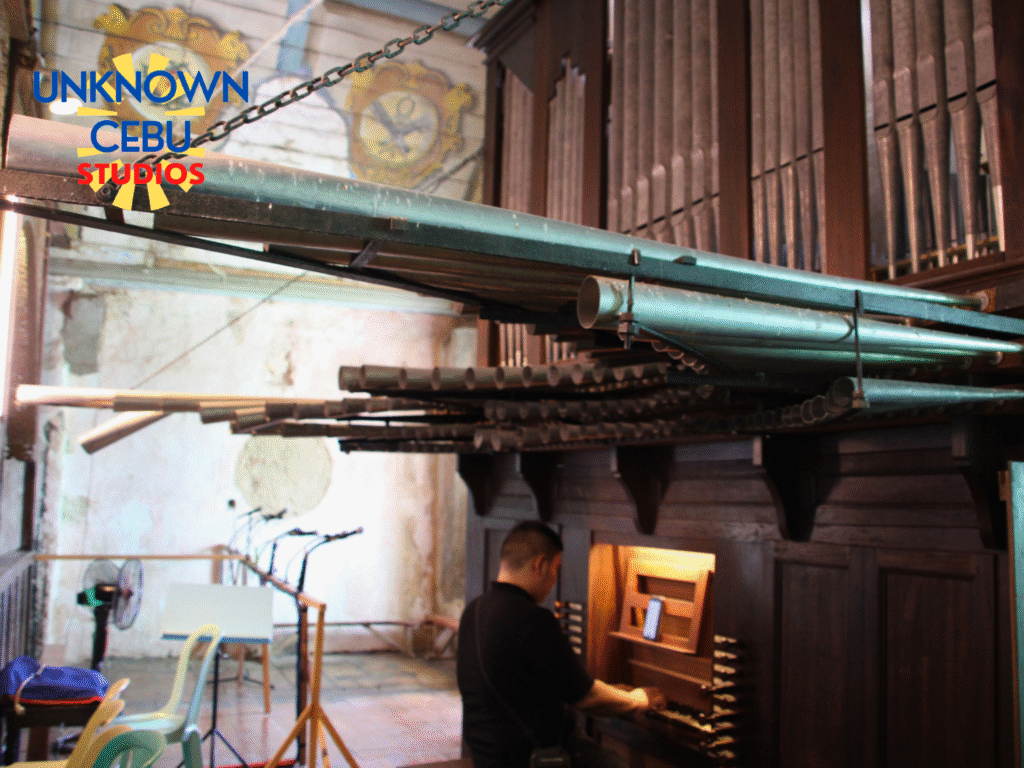

The organ’s provenance as an Otorel-built export model, completed around 1880 as recorded by Fr. Pedro Galende, O.S.A., places it firmly in the late-colonial era, far removed from the earlier, locally-built bespoke instruments. This signals a strategic shift in procurement, leveraging improved logistics to import fully manufactured “standardized twins” directly from Europe. Technically, the instrument is pure Iberian flair. It adheres to the classic Spanish style with a single manual and a pedal division, utilizing the specialized split-keyboard system (teclado partido), which separates the manual functionally into Bass and Discant . This system is essential for performing the Spanish Baroque repertoire, allowing for dramatic solo-and-accompaniment dialogue on a single keyboard. However, the instrument’s most defining feature is its auditory engineering for the fortress-church’s massive acoustic space.

The sonic power required to fill the vast stone nave of the Boljoon fortress is delivered by a complement of six horizontal reed stops, famously known as chamades (Trompetas de Batalla). These high-pressure pipes, projecting straight out into the congregation, include the Trompa Real 8′ and various Clarines. This deliberate inclusion of multiple high-volume, highly directional stops was a key design decision to ensure maximum sonic projection and clarity, necessary for the instrument’s ceremonial character. The organ’s rich disposition also includes the high-pitched Corneta Magna (5 ranks) for brilliant melody and Baroque novelty effects like the Pajarillas (Birdsong) and Campanillas (Bells), underscoring a liturgical aesthetic that favoured elaborate sensory engagement. This combination of musical complexity and sheer projection is a stunning reflection of the Augustinians’ institutional priorities, placing liturgical prestige on equal footing with military defense.

Despite its European pedigree, the organ’s greatest threat was not external attack but the relentless tropical environment. Less than fifty years after installation, the instrument suffered a severe termite (anay) infestation in 1925, necessitating a major overhaul costing P1,153.50. This hefty expense was entirely funded by the devoted local community, including a substantial contribution from the Cofradía, underscoring the immense value placed on the musical heritage even then. Tragically, despite this financial commitment, the organ eventually fell silent for good on September 25, 1964, upon the passing of Silvestre Roma, the last player. For the next five decades, the organ remained a silent sentinel in the choir loft, a monument to a declining local expertise and the harsh realities of sustained tropical maintenance, a fate common to many colonial organs.

The modern turning point was the 2013 earthquake, which damaged the church structure but catalyzed the organ’s salvation. Designated a National Cultural Treasure, the organ’s restoration was integrated into the larger state-funded infrastructure repair project by the NHCP. The specialized technical work was executed between 2016 and 2018 by the premier Filipino firm, the Diego Cera Organ Builders (DCOB). This intervention secured the structure, rebuilt the mechanisms, and addressed the historical termite threat. Crucially, the latest reports confirm that the Boljoon organ has successfully navigated the complex transition from a structurally preserved relic—a status often plagued by the “functionality paradox”—to a fully restored and musically functional instrument. Today, the Organ is in use and will continue to be in use for the foreseeable future, a testament to the fact that the meticulous final phase of musical restoration (voicing and tuning the complex chamade reeds) was successfully completed.

The successful revival of Boljoon’s organ from a silent fortress relic to an active musical monument is a major victory, but the battle for longevity is far from over. The historical threat of the climate demands the immediate implementation of stringent environmental control protocols (humidity regulation and professional pest control) to protect the delicate pipework and mechanism from future decay. To ensure its active life continues, two strategic initiatives are vital: first, the establishment of a Visayan Organ Heritage Circuit utilizing Boljoon, Dalaguete, and the already active Argao organs to attract cultural tourism and guarantee regular, professional usage. Second, a dedicated Endowment Fund must be created to cover perpetual maintenance costs and, most importantly, to fund a local Organ Apprenticeship Program. This initiative will train the next generation of organists and specialized technicians, ensuring that the voice silenced in 1964 is never lost again, securing Boljoon’s golden voice for generations to come.

Sources:

Bamboo Organ Foundation. “Community.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://bamboo-organ.com/community/.

Bohol Provincial Government, Provincial Planning and Development Office (PPDO). “Tourism Master Plan.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://ppdo.bohol.gov.ph/plan-reports/development-plans/tourism-master-plan/.

“Boljoon Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified November 1, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boljoon_Church.

Cubilian, Lizbeth Ann. “Bohol tourism officials step up efforts to restore Spanish-era heritage sites.” Philippine News Agency, December 14, 2017. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1018889.

Delightful.ph. “Heritage-inspired Bellemar Lifestyle Center set to boost tourism in Panglao.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.delightful.ph/blog/category/4/travel-news/post/1004/heritage-inspired-bellemar-lifestyle-center-set-to-boost-tourism-in-panglao.

Diego Cera Organbuilders, Inc. “Services.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://dcob.diegocera.com/services.htm.

ForeverVacation. “Panglao Watchtower.” ForeverVacation. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://forevervacation.com/bohol/panglao-watchtower.

Gallivantrix. “Panglao Watchtower (Tag).” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://gallivantrix.com/tag/panglao-watchtower/.

Gariando, Vangie B. “Cultural agencies come together for Bohol, Visayas.” Lifestyle.Inquirer.net, May 19, 2014. https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/174298/cultural-agencies-come-together-for-bohol-visayas/.

Gerschwiler, Paul. Bolhoon: A Cultural Sketch. The Foundry, 2009.

Guide to the Philippines. “Panglao Watchtower.” Guide to the Philippines. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://guidetothephilippines.ph/destinations-and-attractions/panglao-watchtower.

“Highlights of Panglao Island Tourism Masterplan by Palafox (Part 4 of 4).” Scribd. November 20, 2012. https://www.scribd.com/document/113920526/Highlights-of-Panglao-Island-Tourism-Masterplan-by-Palafox-Part-4-of-4.

Medida, Nozzie Kikoy. Personal Interview. October 30, 2021.

Montemayor, Ma. Teresa. “Cebu’s Argao pipe organ gets long-awaited repair.” Philippine News Agency, January 10, 2025. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1258172.

muog. “Panglao Tower • Panglao, Panglao Island, Bohol.” muog (blog), January 31, 2008. https://muog.wordpress.com/2008/01/31/panglao-tower-%E2%80%A2-panglao-panglao-island-bohol/.

MyCebu.ph. “Boljoon, Cebu Attractions.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/boljoon-cebu-attractions/.

National Historical Commission of the Philippines. 2018 Annual Report. Manila: NHCP, 2019. https://nhcp.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2018-Annual-Report.pdf.

National Museum of the Philippines. “The Patrocinio de Maria Church in Boljoon, Cebu.” November 11, 2021. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2021/11/11/the-patrocinio-de-maria-church-in-boljoon-cebu/.

Orgph.com. “Boljoon.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.orgph.com/organs/boljoon.

Paler, Jemima. “Pipe organ of Argao will be silent no more.” Cebu Daily News, November 27, 2017. https://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/156220/pipe-organ-argao-will-silent-no.

“Panglao, Bohol.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 29, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panglao,_Bohol.

Philsacra, University of Santo Tomas. “UST Philsacra Document (ID: B810677FCB36E5292C3BCE3820982501).” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://philsacra.ust.edu.ph/admin/downloadarticle?id=B810677FCB36E5292C3BCE3820982501.

Philsacra, University of Santo Tomas. “UST Philsacra Document (ID: D1D91EC575AFF405CB235E61C1F72756).” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://philsacra.ust.edu.ph/admin/downloadarticle?id=D1D91EC575AFF405CB235E61C1F72756.

“Raid of Visayas.” Wikipedia. Last modified June 18, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raid_of_Visayas.

Round South Cebu. “History – Boljoon.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://roundsouthcebu.weebly.com/history—boljoon.html.

Sitchon, John Michael. “After 40 years, Argao folk hear shrine’s pipe organ play again.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, December 11, 2017. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/950852/after-40-years-argao-folk-hear-shrines-pipe-organ-play-again.Spl1. Scribd. May 26, 2023. https://www.scribd.com/document/646773418/spl1.

SunStar Cebu. “Argao’s ‘bamboo organ’ plays again.” SunStar, November 29, 2017. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/more-articles/argaos-bamboo-organ-plays-again.

SunStar Cebu. “Rehab on Cebu pre-colonial church near completion.” SunStar, October 16, 2024. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/more-articles/rehab-on-cebu-pre-colonial-church-near-completion.

Suroy.ph. “Boljoon Church Pulpit Returns Home.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://suroy.ph/boljoon-church-pulpit-returns-home/.

U.S. Embassy in Laos. “The U.S. Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation (AFCP).” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://la.usembassy.gov/the-u-s-ambassadors-fund-for-cultural-preservation-afcp/.

U.S. Embassy in the Philippines. “Restoration of Panglao Watchtower, Panglao Island, Bohol.” December 14, 2017. https://ph.usembassy.gov/restoration-panglao-watchtower-panglao-island-bohol/.

u/Raptor_Lover. “Panglao Watchtower in Bohol: One of the few, if not the only…” Reddit, r/Philippines. December 23, 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/Philippines/comments/kjdh7h/panglao-watchtower-in-bohol-one-of-the-few-if-not/.