The air in Dauin, Negros Oriental, today is thick with the promise of world-class diving, but stand by the old stone church of St. Nicholas de Tolentino, and you feel the weight of a far grimmer past. The current coastal parish, Poblacion District 2, is the nucleus of this history, where the local government (LGU) and the church’s cultural heritage commission have forged an alliance to save the town’s most powerful historical artifact. This structure, known locally as a baluarte or watchtower, is more than a ruin; it is a critical, yet fragile, testament to the 18th-century Visayan experience. Unlike the grand fortresses of Cebu or Manila, Dauin’s defense was a localized effort, and its fate rests entirely on the success of this local stewardship. Without it, a key chapter in Central Philippine history could vanish.

The reason for the Dauin Watchtower’s existence is a chilling one: the systematic and devastating Moro Raids that peaked in the mid-1700s. These were not random pirates; they were organized forces focused on capturing native Filipinos for the regional slave trade. These raids had catastrophic demographic and economic consequences, making a formal defensive response an absolute necessity for survival. Historical analysis suggests the tower network, established around the 1750s, was built to counter an entrenched regional dynamic that predated Spanish rule—a “continuation of the pre-Spanish traditions of plundering neighboring kingdoms.” Dauin’s tower, therefore, transcends its colonial financing; it is primarily a monument to the “bravery and heroism of the people of Dauin” and their strategic adaptation against an existential threat.

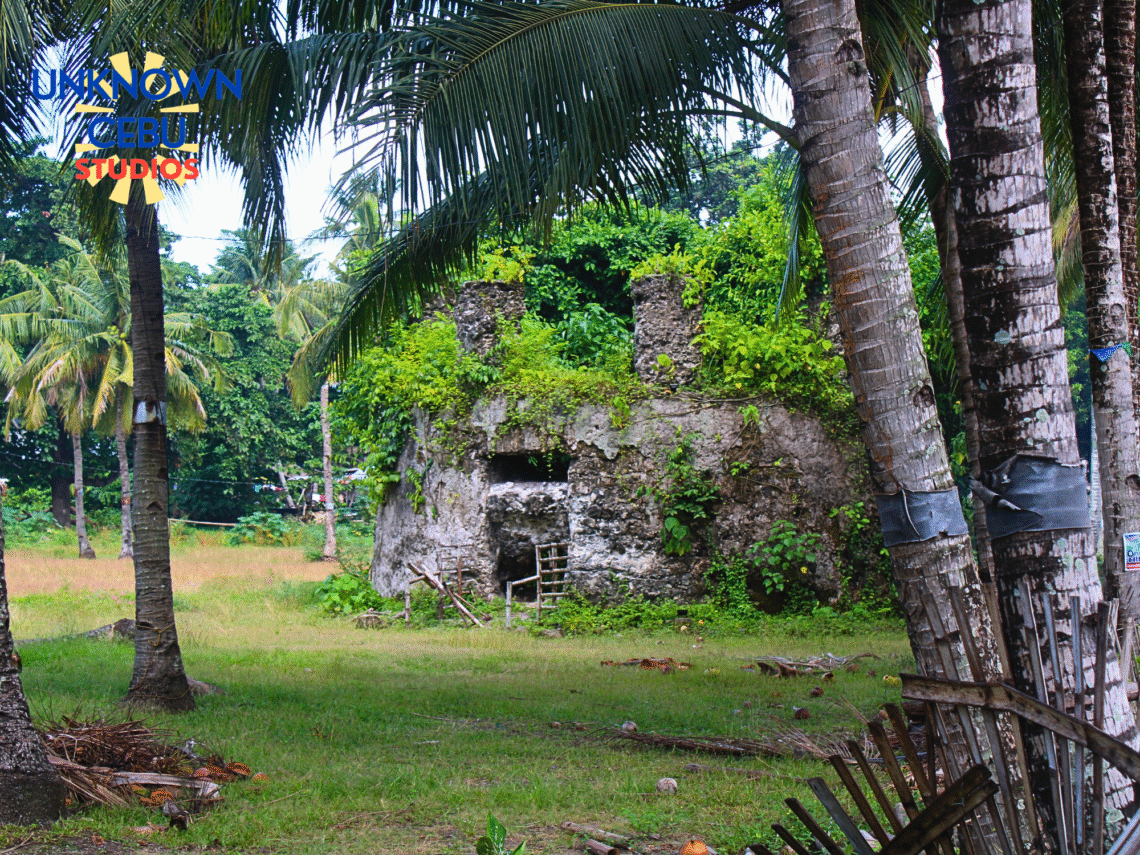

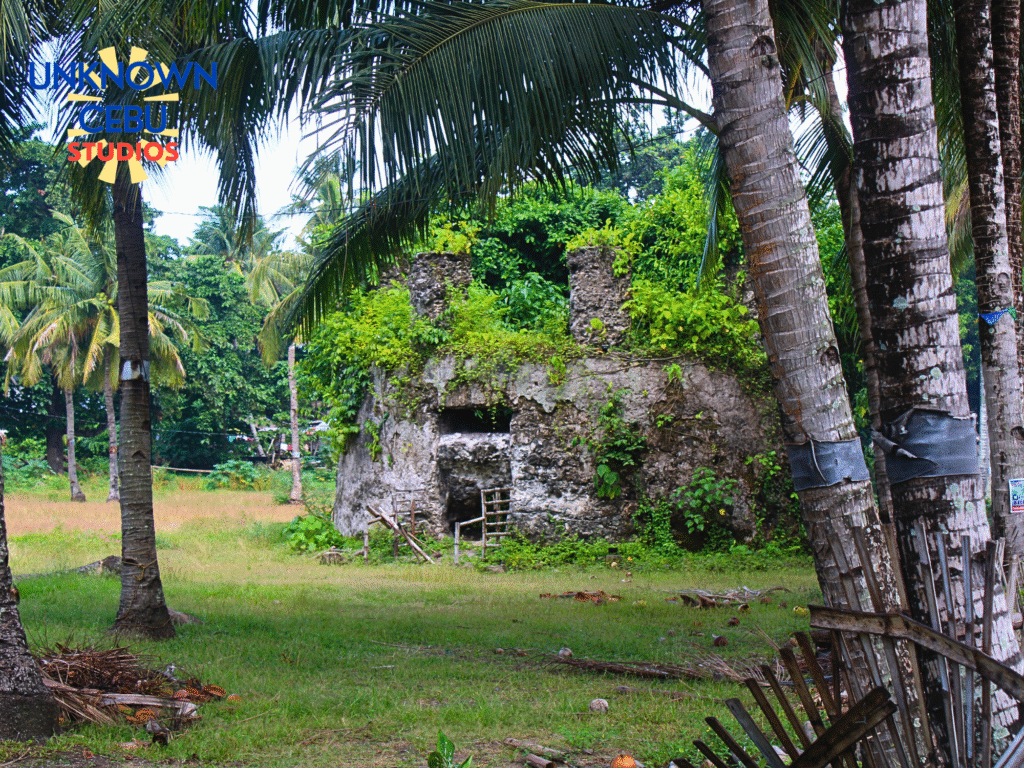

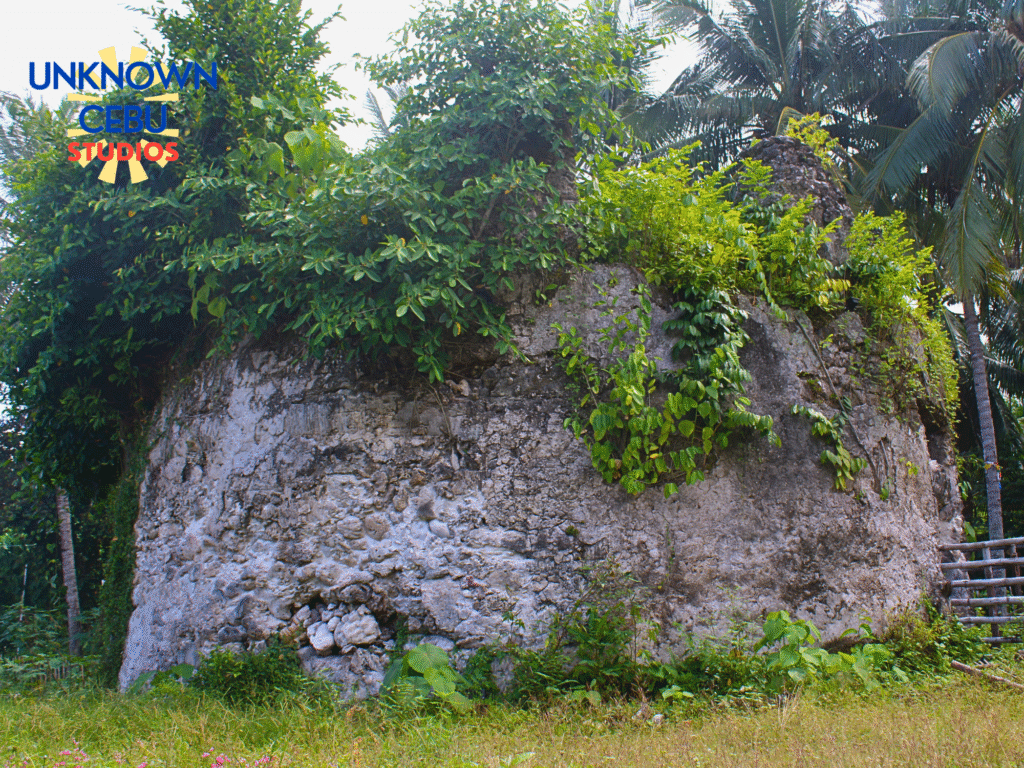

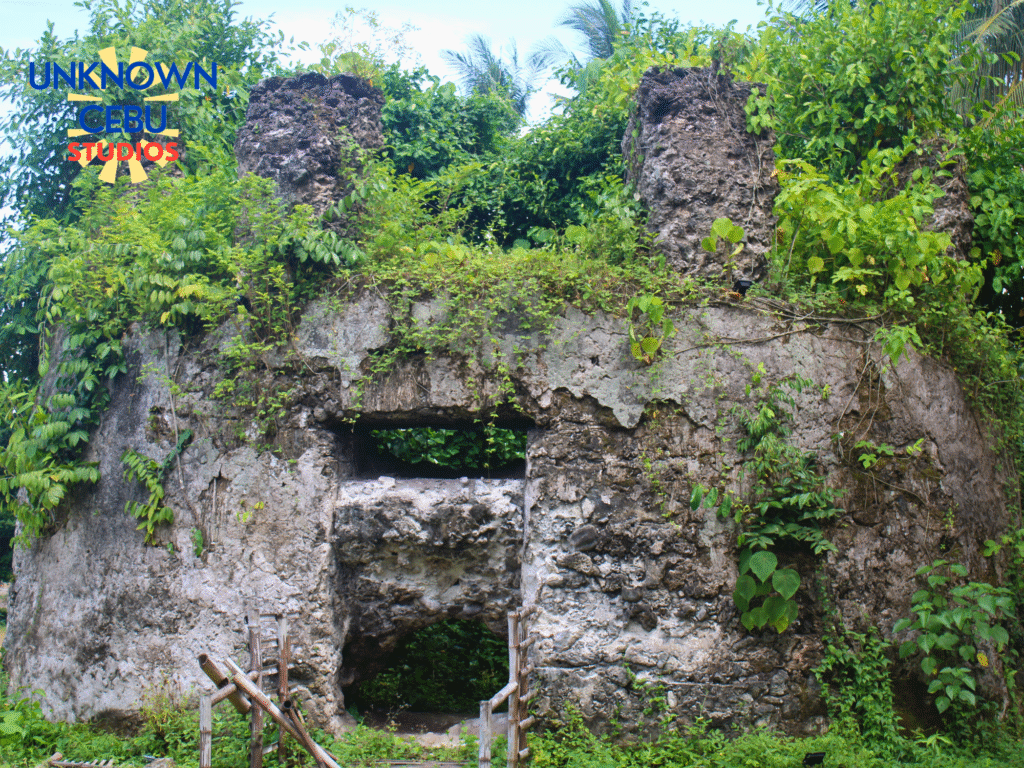

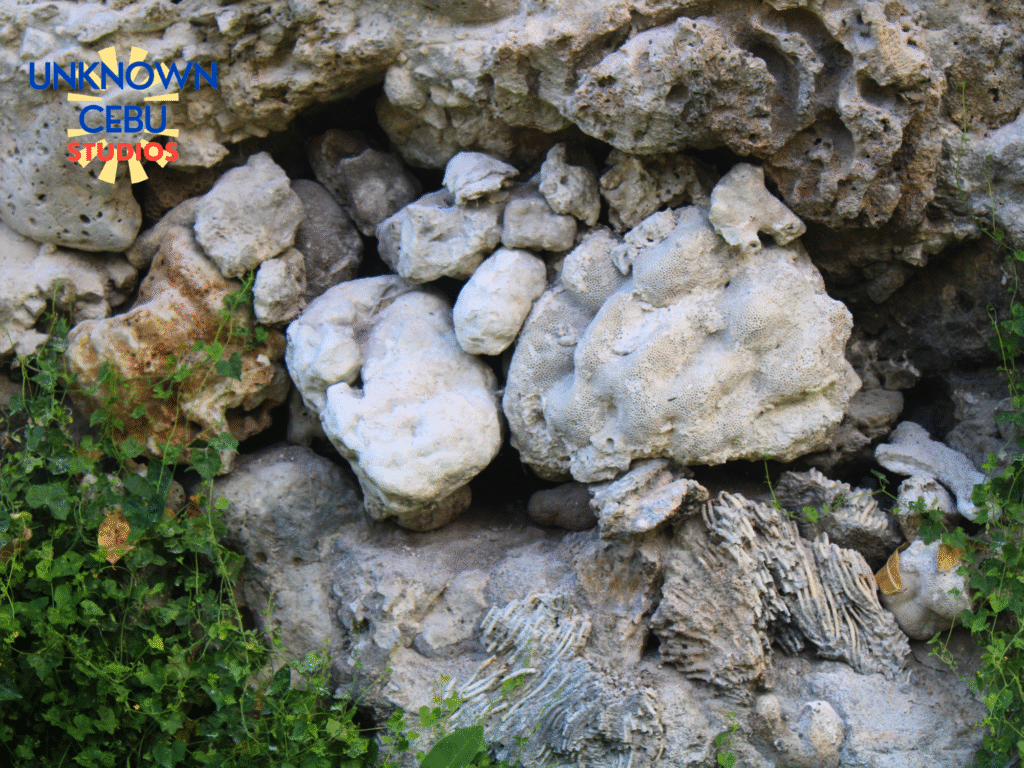

Of the original network of four baluartes built in the 1750s, only the one in Poblacion District 2 remains “mostly intact,” though it is now critically deteriorating. Architecturally, it is a classic colonial torre de vigilancia—a round stone enclosure featuring eight crenellations jutting above the wall. These crenellations—the merlons and gaps—provided essential cover for the watchmen, or bantayans. Its function was a low-resource Early Warning System (EWS): when vintas (raiding vessels) were sighted, the bantayans would use drums to alarm the people, giving them precious time to retreat inland, often to the security of the nearby church compound. Tragically, the fate of one secondary tower serves as a definitive warning: its ruin is now physically “divided” by adjacent dive resorts, a clear demonstration that modern commercial encroachment poses a threat even greater than two centuries of natural decay.

The watchtower’s struggle for survival is a race against time, with the LGU and the Diocese of Dumaguete leading the charge. Recognizing the urgent need for action, their immediate shared objective is structural stabilization to prevent the “chunks of stone and debris continuously falling off.” The long-term plan is far more ambitious: overcoming the current research deficit to develop a scientifically sound conservation plan that will pave the way for formal recognition from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP). Achieving NHCP status would secure national funding and the legal protection necessary for sustained preservation. The ultimate goal is to safeguard this artifact not just for its architecture, but as a cultural vehicle, ensuring the community’s identity as resilient survivors remains a central, unfragmented part of Dauin’s story for generations to come.

Recently, it should be noted, that there have been concrete plans to restore the watchtower beyond the 2020 plan. The parish priest of Dauin (as of November 12, 2025) has already shared plans of turning the vacant lot owned by the diocese into a park for the parish with the watchtower as a central element. The creation of the park will also entail the proper restoration of the watchtower and the addition of a historical marker.

Sources:

Atmosphere Resorts & Spa. “Delightful Dumaguete.” Blog post, November 23, 2017. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://atmosphereresorts.com/delightful-dumaguete/.

Duhaylungsod, Rachel. “INTRODUCTION.” Scribd. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://www.scribd.com/document/550509384/INTRODUCTION.

Javellana, R. “Fortifications of the Visayas.” Muog: Spanish Colonial Fortifications in the Philippines, 1565-1898 (blog), January 24, 2008. https://muog.wordpress.com/2008/01/24/fortifications-of-the-visayas/.

National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Guidelines on the Identification, Classification, and Recognition of Historic Sites and Structures in the Philippines. 2011. https://philhistoricsites.nhcp.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/NHCP-GUIDELINES-ON-THE-IDENTIFICATION-CLASSIFICATION-AND-RECOGNITION-OF-HISTORIC-SITES-AND-STRUCTURES-IN-THE-PHILIPPINES-.pdf.

Non, Domingo M. “Moro Piracy during the Spanish Period and Its Impact.” Southeast Asian Studies 30, no. 4 (March 1993): 401–419. https://kyoto-seas.org/pdf/30/4/300403.pdf.

Partlow, Mary Judaline. “NegOr Town, Church Partner to Preserve Spanish-Era Tower.” Philippine News Agency, September 4, 2020. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1114440.

Wikipedia. “Historical markers of the Philippines.” Last modified October 24, 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_markers_of_the_Philippines.