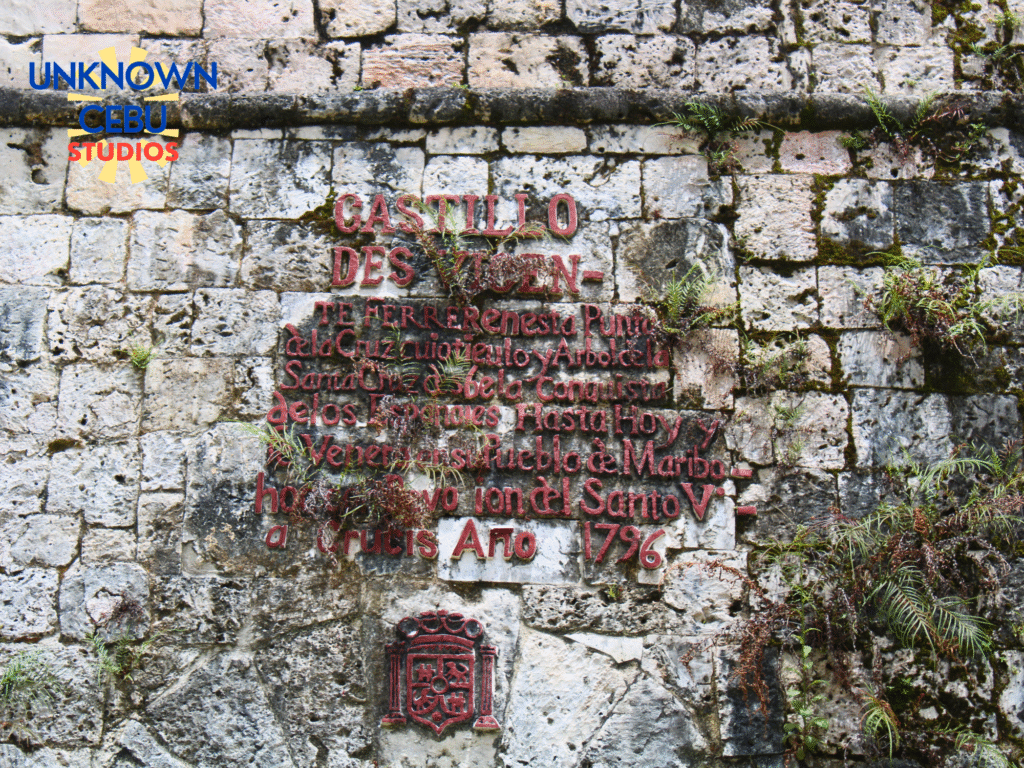

Forget the Chocolate Hills for a second. When you hit Bohol, you’re stepping into an island with a history as sharp as a coral stone cut. And if you’re looking for a monument that perfectly captures the gritty reality of Spanish colonial life—a blend of military grit, ingenious engineering, and spiritual desperation—you need to drive out to Maribojoc and find the Punta Cruz Watchtower. This isn’t just an old tower. Officially the Fuerte de San Vicente Ferrer, it’s a UNESCO-recognized National Cultural Treasure and a tactical masterpiece born from over 300 years of bloody conflict. Its very existence is a testament to the chronic maritime insecurity of the 18th-century Visayas, stemming from the protracted Spanish–Moro conflict. Although Spain claimed regional control, their failure to subdue the Sultanates of Mindanao and Sulu resulted in endemic, politically motivated piracy. These were not random acts; highly organized raiders, including the Illanun, Samal, and Tausug, employed massive, fast warships like the garay and joanga, often armed with small cannons (lantakas). Their primary economic motivation was the capture of human captives for the massive regional slave trade, and Bohol was essentially the pirates’ preferred highway. Centralized fortification, like Fort Pilar in Zamboanga, proved insufficient to protect the far-flung northern Visayas settlements, prompting a critical strategic pivot toward a decentralized network of local, stone watchtowers (or bantayan). The significant capital investment in Maribojoc to construct the Punta Cruz Watchtower in 1796 confirmed the strategic and economic necessity of safeguarding the local Christian population and essential trade routes against this persistent and severe maritime threat.

The tower’s location, strategically positioned at the westernmost tip of Maribojoc, was selected for optimal maritime surveillance. From this elevated position, sentinels commanded extensive, panoramic views of the Bohol Strait, allowing for the observation of critical navigation corridors and distant islands, including Cebu and Siquijor. The structure’s primary function was early warning, tasked with providing the necessary temporal buffer for the community, located approximately three kilometers (1.9 mi) away at the Maribojoc Church, to mobilize their defense or evacuate inland. But this defense wasn’t random; the structure’s tactical ingenuity lies in its geometry. This is the tower’s secret weapon and its claim to fame: it is the only perfect isosceles triangle tower-fort structure in the entire Philippines. This design is far from accidental; it is a calculated military rationale optimized against a predetermined threat. The sharp, pointed apex of the triangular base is pointed directly out to the open sea—the precise direction the Moro raiders consistently came from (the south). This “Apex Advantage” achieves two primary defensive goals: minimizing the target profile by presenting the smallest possible surface area to incoming naval projectile fire, maximizing the chance of projectiles glancing off the reinforced masonry, and concentrating the bulk of the structure’s massive coral stone masonry along the vector of greatest threat. The structure further transitions from this defensive triangle base to a compact hexagonal tower on the second level, maximizing the functional internal space necessary for sentries while retaining the compact, defensible footprint below.

Who designed this masterpiece? Not a centralized military engineer, but the Augustinian Recollect priest, Father Manuel Sanchez de Nuestra Sra. del Tremendal. The entire Bohol defense network was a product of Ecclesiastical Engineering, which positioned the parish priest not only as a spiritual leader but also as the de facto architect, engineer, and financier of local public works and defensive structures. This autonomy, necessary because centralized military engineers were focused on major fortifications, resulted in the extreme architectural diversity observed across Bohol’s defense network. Standardized imperial blueprints were rarely enforced, allowing local leadership to develop site-specific designs optimized for local materials (coral stone) and the precise tactical demands of their location. The unique isosceles triangle design of Punta Cruz, therefore, is not a product of rigid Spanish military doctrine, but a localized architectural innovation developed by Fr. Sanchez or his local maestro de obras to address the specific threat vector targeting Maribojoc. This contrasts sharply with the slender hexagonal Dauis Watchtower, known for its ornate Medieval European woodwork, or the Panglao Watchtower, the tallest in the archipelago with a curved silhouette that some historians suggest is reminiscent of Chinese pagodas. This heterogeneity highlights a fundamental trade-off: decentralization allowed for rapid, site-specific optimization but ultimately precluded the use of standardized, highly resilient structural systems, leading to uneven durability across the network.

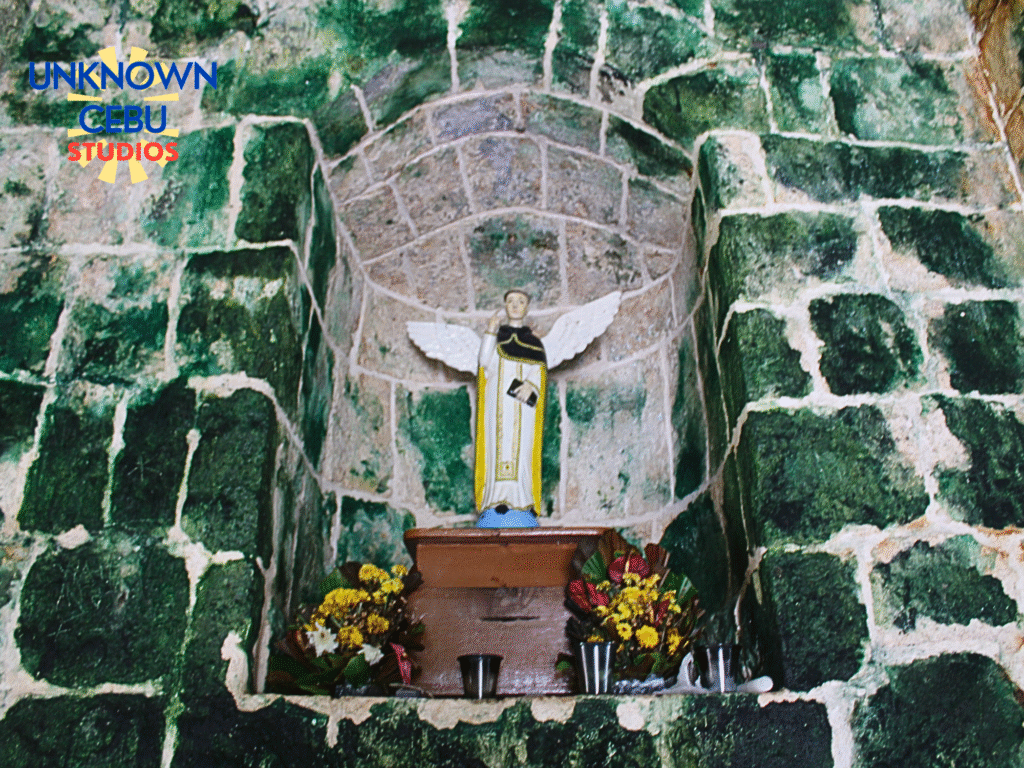

Beyond its physical architecture, the tower is deeply woven into the spiritual and cultural fabric of the community. Its official dedication as the Fuerte de San Vicente Ferrer and the internal niche designated for a religious image of the saint reflect the colonial-era practice of integrating military necessity with spiritual reliance, acknowledging that community defense required both human ingenuity and divine protection. Integral to the site’s folklore is the local belief that the wooden cross near the tower possessed mystical powers, actively protecting the area from marauders. Specifically, the legend recounts that a “glaring light” would emanate from the cross, terrifying and disorienting the approaching pirates, making it difficult for them to sight the land and mount an attack. This narrative, however, is a remarkable cultural preservation of technical memory. The “glaring light” is highly suggestive of the successful deployment of reflective signaling devices (such as polished metal or mirrors) used by the sentinels stationed atop the tower. These rapid light signals, transmitted across the 3-kilometer distance to the main Maribojoc parish, were the tactical key to alerting the town. The efficacy of this early warning system, crucial for the community’s survival, was ultimately reinterpreted through a spiritual lens, reinforcing local faith while functionally documenting a sophisticated tactical communication system essential for the network’s interoperability.

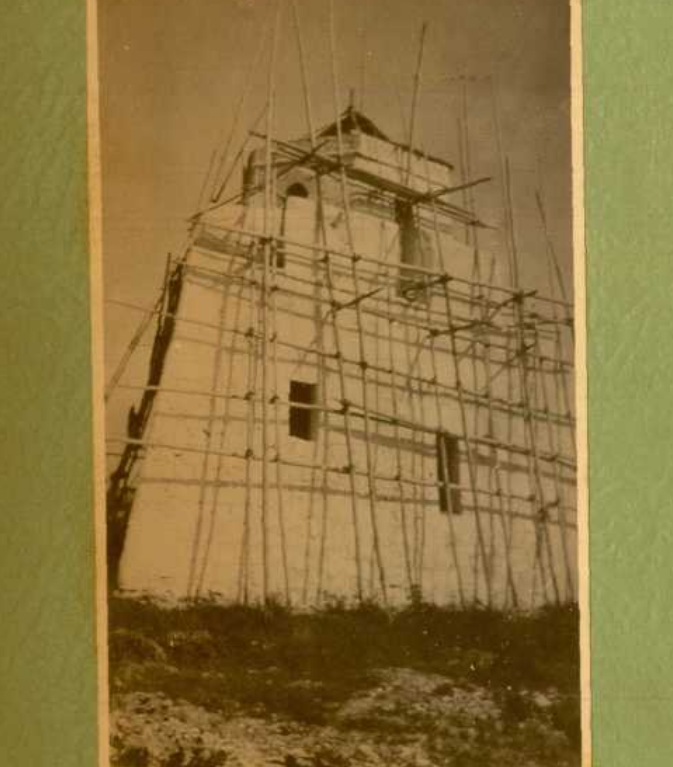

However, the tower’s biggest challenge wasn’t a pirate’s cannonball, but the Magnitude 7.2 Bohol earthquake of October 15, 2013. This event introduced intense, multi-directional lateral forces that severely tested the century-old masonry structure. A technical assessment determined that the watchtower sustained moderate to serious damage, primarily a consequence of the material limitations inherent in its unreinforced coral stone masonry. While the massive construction provided high compressive strength, ideal for resisting vertical loads and frontal directional impacts, it exhibited extremely low tensile and shear strength. Under the intense lateral ground movement, the brittle masonry suffered catastrophic failure through shear cracking and fragmentation. The structure’s unique triangular geometry, optimized for defense against a naval threat, offered no intrinsic mitigation against tectonic forces. The failure was a classic case of unreinforced masonry structure vulnerability to lateral movement, compounded by the low compressive strength of the air-hardening lime binder, which led to the detachment of stone wythes and loss of structural cohesion.

The tower’s designation as a National Cultural Treasure ensured its restoration was a high priority, with a rigorous, three-year conservation effort successfully restoring the structure to its original state by 2016. The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) implemented a sophisticated conservation strategy guided by the principle of authenticity and material compatibility, establishing a critical benchmark for heritage management in seismically active regions. Restoration utilized traditional methods, employing compatible, lime-based mortars to replace failed historic binders. Crucially, the NHCP explicitly avoided the use of non-traditional, irreversible materials, such as epoxy resins, on the porous coral stone masonry, preventing the introduction of incompatible stiffness and stress concentrations that could lead to long-term structural pathology. To ensure the structure’s long-term survivability against future seismic events, the conservation team integrated discrete modern retrofitting methods—a strategy of “engineered authenticity.” Techniques included grout injection to re-establish the cohesion of the thick stone mass and, critically, enhancing the structural connections between the wooden floor beams (diaphragms) and the masonry walls to prevent out-of-plane failure during lateral shaking.

Today, the Punta Cruz Watchtower stands fully restored, a dynamic blend of deep history and advanced conservation. Its survival and successful restoration underscore a modern commitment to heritage stewardship: one that mandates the strict use of traditional materials while judiciously integrating discreet, contemporary seismic retrofitting. Owned and managed by the Municipality of Maribojoc, the site now serves as a cultural and scenic hub, drawing visitors interested in its history and its commanding vantage point, especially at sunset over the Bohol Strait. The structure remains actively integrated into local communal life through the annual “Pista sa Punta Cruz,” a religious and cultural festival. This continuous use and integration into local identity are vital for sustainable heritage adaptation, ensuring the physical structure receives ongoing stewardship and contributes positively to local economic development through cultural tourism. The Fuerte de San Vicente Ferrer is not just an architectural artifact; it is a vital case study in disaster risk reduction and a living symbol of localized resilience against both historical maritime threats and modern tectonic forces.

Sources:

Garciano, Arturo A., and Lessandro O. Garciano. “Integrating the Heritage and Disaster Mitigation Concerns on Cultural Heritage Sites in the Philippines.” Full Scale Inter-Disciplinary Research on Disaster Mitigation and Rehabilitation in the Philippines: Focused on the 2013 Bohol Earthquake, Japan Society of Civil Engineers, 2016. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://committees.jsce.or.jp/disaster/system/files/FSID28_Garciano_DisasterMitigation.pdf.

“Sultanates, Slavery, and Resistance in the Visayas.” Kyoto Southeast Asian Studies 30, no. 4 (2020): 3–21. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://kyoto-seas.org/pdf/30/4/300403.pdf.

“Material Analysis of Spanish Colonial Coral Stone Masonry in the Philippines.” Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage (Journal of the University of Bologna), 2024. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://conservation-science.unibo.it/article/view/7164.

Maribojoc Municipal Government. “History of Maribojoc.” Accessed November 18, 2025. http://www.maribojoc.gov.ph/about/history. (This source is also available via the Web Archive link provided: https://web.archive.org/web/20140908181133/http://www.maribojoc.gov.ph/about/history).

“Quimica Del Mortero De Cal Del Siglo XIX En Una Tabique Pampa.” Dialnet. Accessed November 18, 2025. (This citation is based on the file name metadata, as the source was provided as a local file path: file:///C:/Users/Atom/Downloads/...).

Pista sa Maribojoc Organization. “Pista’s History.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.pista.org/pista-s-history.

Wikipedia. “Punta Cruz Watchtower.” Last modified November 1, 2025. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punta_Cruz_Watchtower.

Wikipedia. “Spanish–Moro conflict.” Last modified November 10, 2025. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish%E2%80%93Moro_conflict.

Guide to the Philippines. “Punta Cruz Watch Tower.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://guidetothephilippines.ph/destinations-and-attractions/punta-cruz-watch-tower.

Bohol.ph. “Punta Cruz Watchtower, Maribojoc.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.bohol.ph/diksyunaryo.php/layout/banner/pics/thumbs/article17.html.

OAR History. “Augustinian Recollects History.” Blog post, August 2011. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://oarhistory.blogspot.com/2011/08/.

Trawlercat. “The Moro Pirates and Their Reign of Terror in the Philippines.” Blog post, August 12, 2025. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://trawlercat.com/2025/08/12/the-moro-pirates-and-their-reign-of-terror-in-the-philippines/.

Coconote. “Note ID: 87d4560b-1add-4011-a842-aacf27f86541.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://coconote.app/notes/87d4560b-1add-4011-a842-aacf27f86541.

Forever Vacation. “Punta Cruz Watch Tower, Bohol.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://forevervacation.com/bohol/punta-cruz-watch-tower.

Evendo. “Dauis Watchtower.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://evendo.com/locations/philippines/central-visayas/attraction/dauis-watchtower.

Nitmart. “History of Bohol.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://nitmart.tripod.com/HStory05.htm.

Nitmart. “Places of Interest in Bohol.” Accessed November 18, 2025. https://nitmart.tripod.com/Ntrest06.htm.

Reddit. “What incentivized Moro raids on the Visayas?” r/FilipinoHistory. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/FilipinoHistory/comments/1k17x7q/what-incentivized-moro-raids-on-the-visayas/.