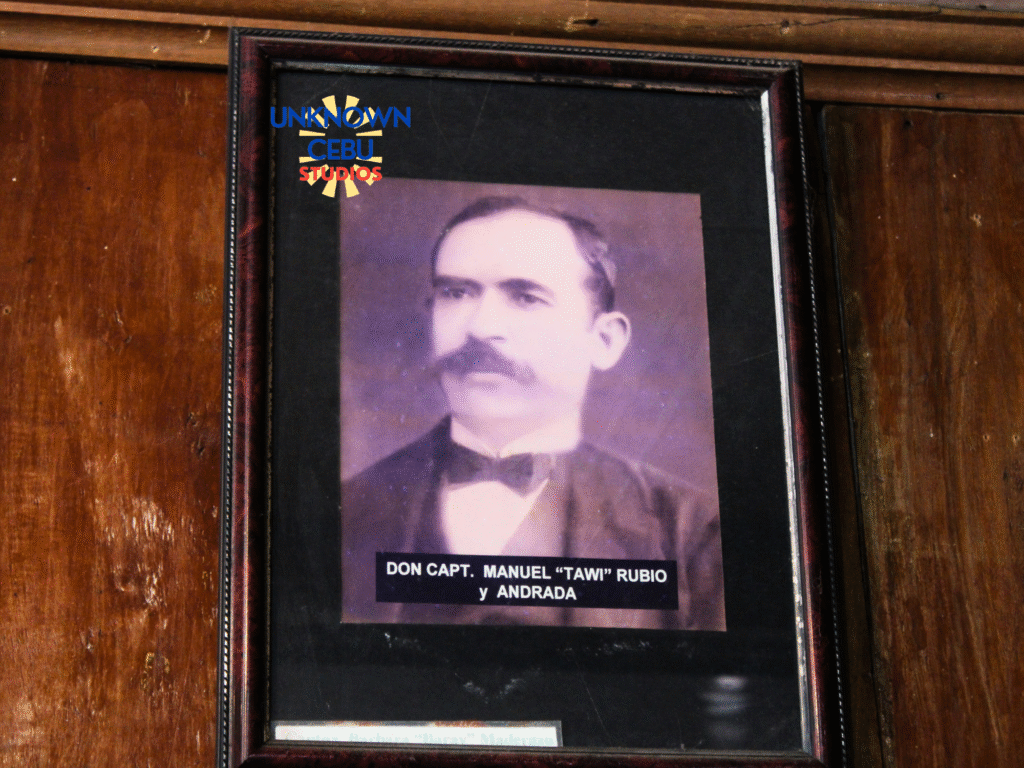

Long before Bantayan Island became a traveler’s refuge of white beaches and slow tides, it was a frontier where coral walls, coconut groves, and watchtowers stood guard against the uncertainties of the sea. Into this older Bantayan arrived a young migrant from Panay around the 1830s: Manuel Rubio y del Rosario, later remembered simply as Capitan Tawi. Born around 1820, likely in Capiz, Rubio came under the protection of his uncle, the Augustinian priest Doroteo Andrade del Rosario, who guided the parish and envisioned a grand new stone church for the island. Rubio began quietly as an aide in the convento, but his gift for managing men, tools, and materials quickly surfaced. By 1839 he was named maestro de obras, master-builder of the coral-stone church of Saints Peter and Paul. Under his direction, the first coral blocks were carved, shaped, and laid into the walls that still rise over the plaza today, glowing pale in the afternoon sun like the remains of a dream built with patience and salt air.

Local memory, passed from elders on porches and under mango shade, recalls that Rubio brought more than fifty craftsmen from Capiz to assist in the monumental construction. These were not ordinary laborers but skilled masons and carpenters who understood how to work coral stone with both strength and delicacy. Together they carved thousands of blocks from reefs and upland quarries, curing them in the heat before stacking them into the thick walls that insulated the church from wind, sun, and time. At the same moment they raised the bantayanes, the lookout towers that gave the island its name, where sentries scanned the horizon for Moro raiders. It was an era when faith and defense blended seamlessly, and architecture served as the island’s most dependable guardian. Rubio stood at the center of this effort. By the time the church reached completion in the early 1860s, he had proven himself not only a builder of stone but a steward of community security and pride.

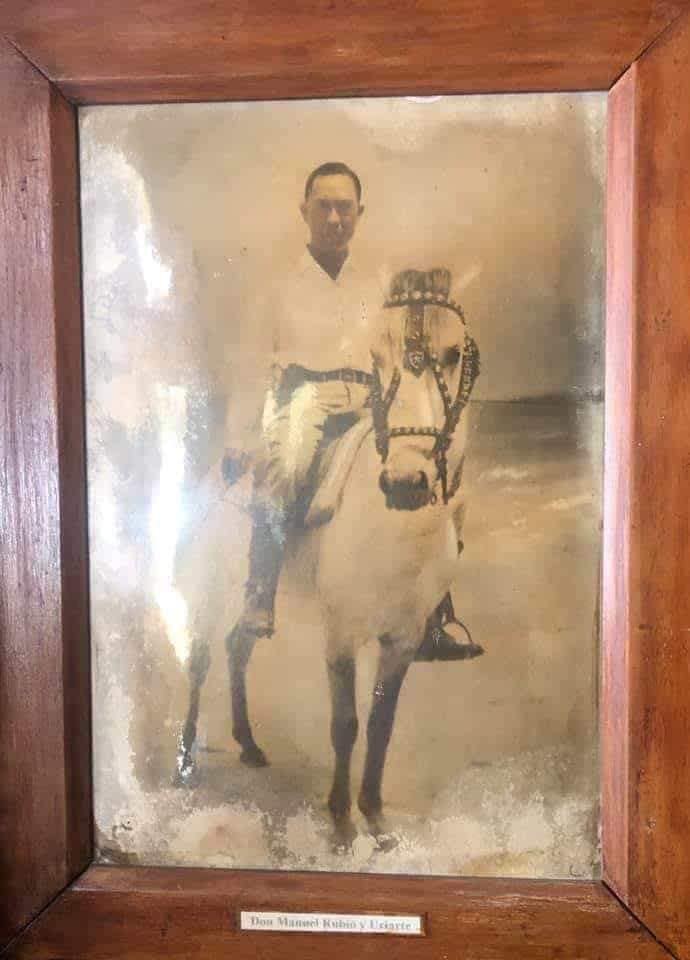

Once he had established himself in Bantayan, Rubio expanded from architecture into land, agriculture, and inter-island trade with the same determination that marked his church work. By the 1870s he had become one of the island’s largest landowners, holding an immense stretch of farmland and forest estimated between 1,500 and 1,800 hectares. On these lands he planted coconut and corn, produced tuba, and organized fleets of paraws and cargo boats that sailed regularly between Bantayan and Panay. With land came wealth, and with wealth came civic responsibility. By the late 1870s the colonial government appointed him gobernadorcillo of Santa Fe, the old municipal name of Bantayan town. It was here that the nickname Capitan Tawi took hold, a title spoken with familiarity and respect in the community. His marriage to Doña Bárbara Maderazo tied him to one of Bantayan’s established clans, and his children, Francisco and María, married into families of equal stature, weaving Rubio’s lineage firmly into the island’s political and economic fabric.

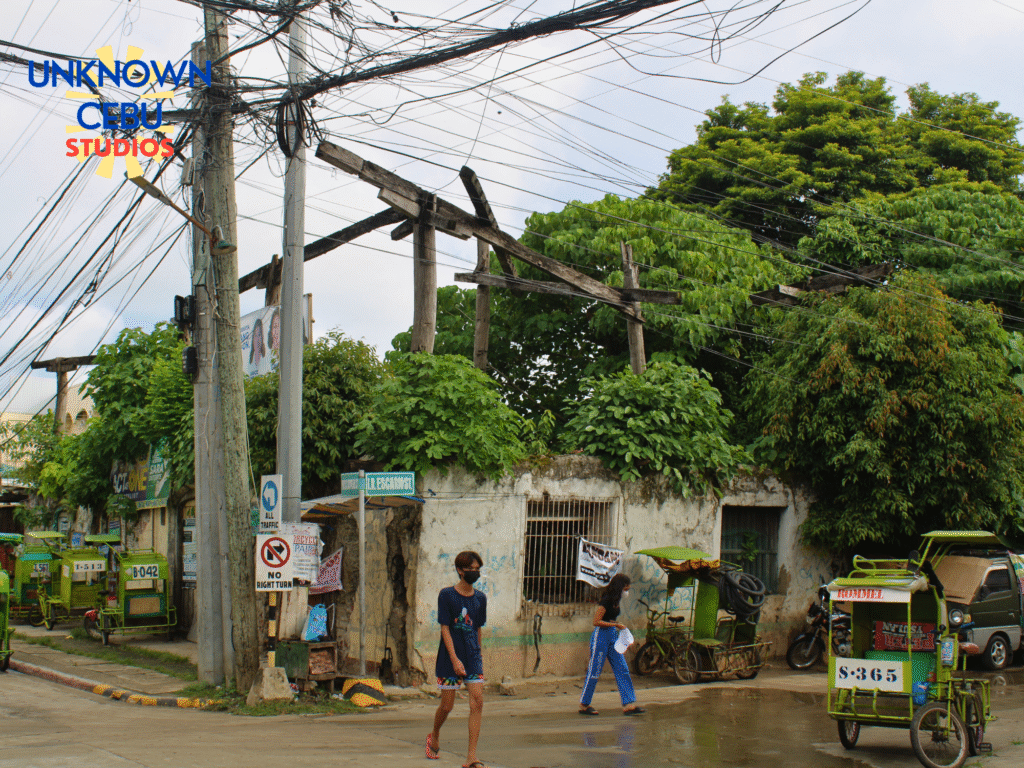

For all his land and trading success, nothing displayed Capitan Tawi’s stature more vividly than the three grand bahay na bato he constructed around the church plaza, a trio of coral-and-hardwood mansions that once formed a proud architectural ensemble at the town’s heart. The first, built in 1836 and known as Casa de Teja or Balay na Tisa, combined coral-stone walls on the ground floor with a hardwood upper level crowned by red clay tiles imported from Panay. It served both as residence and as the Casa de Mampostería during church construction. The second house, built around 1880, matched the first in elegance and may have commemorated the marriage of his son Francisco. The third, erected in the early 1880s and roofed with zinc to comply with new ordinances, was the grandest of the three. Rubio gifted it to his daughter María when she married Margarito Escario, a union that strengthened ties with another prominent Bantayan family. Time has been less kind to the first two houses, which eventually collapsed after years of neglect and, in one case, the devastation of Typhoon Yolanda in 2013. The third house, however, still stands proudly on the plaza, its capiz windows filtering the same golden light that once lit the footsteps of the Rubio and Escario clans.

By the end of the nineteenth century, as Rubio grew older, his name had already settled into the collective memory of the island. He had helped build the great church that became Bantayan’s enduring landmark. He had shaped the municipality through his tenure as gobernadorcillo. He had strengthened the island’s economic life through agriculture, tuba production, and trade. And he had left behind three monumental houses that redefined the architectural presence of the plaza. Though the exact year of his death remains uncertain and many documents disappeared with time, storms, and upheaval, the places he shaped remain unmistakable markers of his life. The coral-stone church still presides over the plaza. One of his houses still stands with its capiz windows glowing at sunset. And a quiet street named Capitan Tawi still carries his memory in the everyday rhythm of Bantayan. Walk through the old town and you can almost imagine him there: a builder surveying coral blocks, a trader loading boats for Panay, a civic leader presiding over local affairs. In a place where heritage often hides behind modern storefronts and beach-bound traffic, Capitan Tawi remains in the very layout of Bantayan’s heart, in the stones he placed and the community he helped shape. A remnant of his massive legacy is present in the home museum maintained by Dreksel Rubio in one of the three grand bahay na bato which features artifacts from the Rubio Family. |UnknownCebuStudios|

Sources: Bersales, Jose Eleazar R. “Looking for Capitan Tawi: Memory and Myth-Making in Bantayan Island, Cebu.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture & Society 41, no. 3/4 (2013): 295-314.

“Rubio Ancestral House Museum of Bantayan.” UnknownCebu blog, Nov. 16, 2024. https://unknowncebu.com/2024/11/16/rubio-ancestral-house-museum-of-bantayan/

“Bantayan, Cebu: Architecture & Description.” BantayanIsland.info. Accessed November 14, 2025. https://bantayanisland.info/information/about/

“Bantayan.” The Philippine Star, Aug. 7, 2005.

“G.R. No. 147877 – Siacor v.…” Supreme Court of the Philippines eLibrary. Accessed November 14, 2025. https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/1/50693