Once there was a church so grand, so magnificent in the eyes of many a person that it drew the admiration, and in some cases ire of those around it. A place of worship that was truly something to behold, its opulence something that many a traveler would write about. A place where throughout it’s long and storied history would be remembered even as it was demolished and erased from living memory. Barely anything stands of what once was of Parian’s San Juan Bautista church today as evidence to what was once there, however through the records and witnesses that have survived a clear narrative can be established. The narrative of how Cebu’s Parian Church was mostly erased from existence.

From: Cebuano Studies Center

It was the dawn of a new era of commerce and prosperity for the burgeoning community of the Parian district just north of the city. The area was set up as a community of Chinese traders during the 16th-17th with settlers from China either coming with their families or intermarrying with the local Cebuanas. From this point the Chinese, otherwise known as Sangley or Mestizo de Sangley expanded their reach from their once little holdout collection of houses a bit north of the main seat of power over in the tightly knit city center where landmarks like the Ayuntamiento, Cathedral and Fort San Pedro Stood, all the way to having some sway of influence in lands located in Talamban. At the turn of the 18th century economic policies were becoming less stringent to the point of majorly increasing trade in Cebu and thus the gradual prosperity of the Chinese, Spanish and Native Cebuano alike. Trade was the first business of this area which then moved to exportation of agricultural goods similar to the situation in the north of the Colony as Manila opened its ports to international trade.

The Parish of San Juan Bautista began life on October 22, 1614 when Cebu was divided into three parishes by Bishop Pedro De Arca. Again there is a divide here with a parish in the form of the Cathedral, representing the Spanish, the Native Cebuanos or Naturales in the form of San Nicolas and Parian’s parish representing the Chinese Mestizo community.

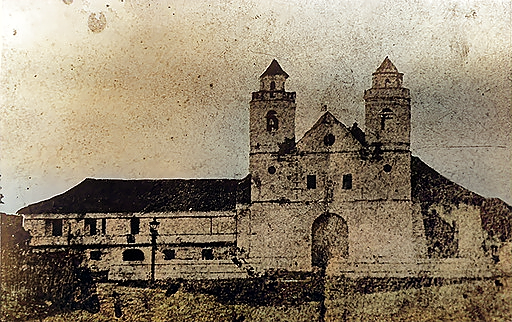

Parian’s prosperity shone like a beacon to the rest of Cebu with the community having built a large church “The church was made of stone blocks, plastered together in a mixture of lime and the sap of the lawat tree. The roofs were made of tiles, and the lumber used was molave, balayong and naga” says one source which denoted a significant amount of expenditure in terms of labor and material costs. This church which had its construction date put around 1602 or sometime in the 17th century was a marvel according to those who were able to visit. It was described as a church that has no equal in the island of Cebu. The coral stone church and adjoining convent on the left side when facing its façade appeared to be built in the baroque style with two four tiered bell towers on each flank giving it a recognizable silhouette. The bells in each tower were reportedly so loud that they could be heard as far as Talisay to the south; a full 10 kilometers away. The church reportedly used mass paraphernalia made of Gold, “the altars were covered with stone slabs with money and gold inlaid, and the church bells were big and loud.”

The church had a very ideal location being at the center of Parian and in conjunction to being its center also had a position at the crossroads of several streets, all of which terminated at the triangular Plaza at the front of the church which would later become a landmark of Cebu in its own right even when what was behind it fell. The gravity of the Parish and its place in the center is still evident to this day with the grand mansion of the Gorordo Family being walking distance from the epistle (right) side of the church. The museum known today as the Jesuit house was built in the year 1730 and is the oldest dated house in the Philippines; it too was built with the labor of Chinese artisans and is located mere steps from the San Juan Bautista Parish. The Yap-Sandiego house was located right across the street and still exists today. The point being that this church was important to the community that it helped create and vice versa. This towering edifice, a testament to its impact on the economic, religious, and political stage of Cebu.

The splendor of the Parish in Parian outstripped that of the Cathedral, a Parish that was wealthier, better built and better maintained than even the one at what was supposedly the center for power. In 1828 the Bishop of Cebu with the support of the provincial governor, had the parish abolished. The people of Parian may not have taken it as a complete surprise as there had already been religious controversies which under underpinned the decision to abolish the Parish and subsequently order its parishioners to attend mass at the Cathedral. With this abolishment, the citizens of not just Parian, but also the Cathedral Parish protested and appealed to the governor-general of the Philippines at the time, Pascual Enrile y Salcedo

The struggle to keep the doors of the church open went through a back and forth between representatives of both sides. The Bishop of Cebu and the governor-general had a mutual distaste for following the decrees of the other. Sometime in 1832, the church of Parian was ordered closed to the public with the fate of all of its treasures unknown. There was a brief respite in 1839 when the decision to close the parish was disputed and reversed, but it was all in vain as the Bishop of Cebu once again ordered its closure. The result of rooting tension between the priests of the cathedral and the priests and officials of Parian. From there the church saw very limited use.

Enter, Dionisio Alo, gremio capitan at the time who was there when the centuries old Church, the one he had known for most of life had begun to be demolished piece by piece. This was in the year 1878, the year when it was decided to fully demolish the church; to strip away its stones, take down its walls, essentially to erase the symbol of power and prosperity which had so long stood in contrast to the supposed superiority of the Cathedral. Before the eyes of this man was the systematic dismantling of what was the most opulent church in Cebu. His vocal opposition made him enemies, however there was no longer anything that could be done. Slowly, but surely everything was taken away leaving nothing left save for the convent, spared as there was still some use that could be found for it. The convent would later serve as a fire station, which would be its fate up to this day. Dionisio Alo passed away in 1887 and was buried in Carcar. This whole episode and his reactions along with his opposition to the destruction occurring right in front of him is recorded in Felix Sales’ Ang Sugbo sa Karaang Panahon published in 1935.

Before World War 2 a cross stood on the ruins of the altar as a reminder of what once was.

The remnants of the demolished church are spread far and wide around the Visayas. Some say that the still usable coral stone blocks of the church went to the completion of the Carcel de Sugbo infirmary that is now part of the Museo Sugbo complex. The big bells whose tolling could be heard as far as Talisay were given to other parishes, one ended up in the Cathedral, and another went as far as far as to cross the Cebu strait to the Parish of Calape, Bohol where it hangs today. Some pieces of Baldoza tiles from the church are now in the Cebu City Museum where they are on display. The church lives on through scant photographs and in museums as displays or models. On the Heritage of Cebu monument is a depiction of the church alongside the Cathedral and Basilica Minore Del Santo Nino.

Read also: How A centuries old image was saved from a fire in Bantayan

Thus ends the tale of how Cebu lost one of its oldest and most beautiful churches to the clutches of jealousy, hatred and pride. Many questions remain unanswered like where did the interiors of the church go? Where are the photos of the demolition? and such that will likely remain unanswered. It is how the world works that great witnesses to the development of a people, a culture, an identity can be undone by the malice of a single generation. The multitudinal multiciplity of the failures of man.

Sources: Life in Old Parian – Concepcion G. Briones

Sources: Fenner, B. L. (1985). Cebu under the Spanish flag, 1521-1896: An economic-social history. San Carlos Publications, University of San Carlos.

Sources:Mojares, R. B. (2017). Casa Gorordo in Cebu: Urban residence in a Philippine Province, 1860-1920. Ramon Aboitiz Foundation, Inc.

Sources: Felix Sales’ Ang Sugbo sa Karaang Panahon, 1935